No one word: Latino identity in Minnesota

by Molly Bloom, Minnesota Public Radio

July 11, 2013

The demographics of Minnesota are changing and the growing Latino community is an important part of that change. We collected the stories of more than 125 Latinos in Minnesota and asked them to choose five words or phrases that describe their identities. These Minnesotans trace their roots to 17 different countries. Some of their families have been here for generations, while others have recently arrived. Click on the images below to read their stories. Click here to read more about the project.

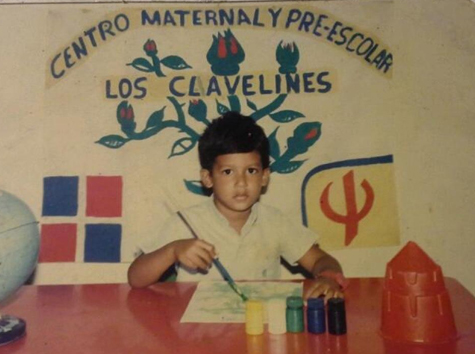

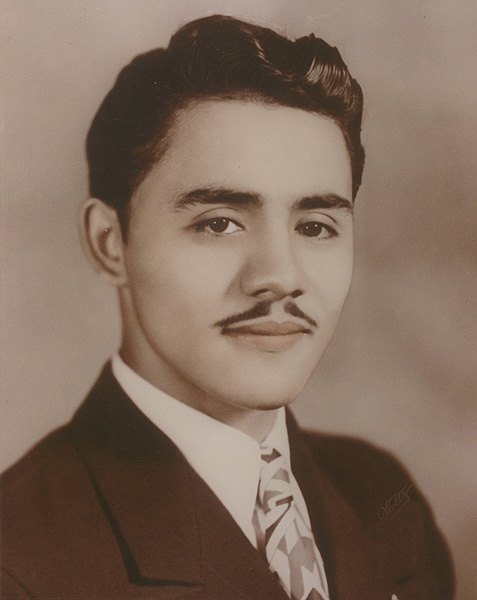

Joe LaTorre, Coon Rapids

Joe LaTorre, 32, lives in Coon Rapids where he was born and raised. His father is Colombian and his mother's family is originally from Bemidji, but he did not speak Spanish nor know much about his Colombian heritage until he visited Colombia in his late 20s at the urging of his sister. His life has changed since his visit to Colombia, including his engagement to a woman he met there. LaTorre is currently going through the process of applying for a visa for his fiancee to join him in Minnesota.

Mayra Quiterio, St. Paul

Tres palabras: Mexicana, madre, hija

Three words: Mexican, mother, daughter

Yo siempre digo que soy Mexicana. Ese término de Latino ya se que como que se uso así para diferenciar entre las...está un poco racista, a mi en lo personal. Porque...dices, OK, eres Anglo. Ya cuando te dicen Latina, eres así como te...de los Estados Unidos, para abajo, México, El Salvador, Honduras, donde sea...Yo los tomo así. Porque realmente todos somos norteamericanos. En este aspecto todos somos norteamericanos, seamos Latinos or somos Anglos.

Es difícil hacer un balance. Y más cuando hay hijos de por medio. Por qué? Porque tienes que transmitir tu cultura a tus hijos para que ellos también vayan creciendo con las dos culturas.

¿Piensa quedarse aquí en los Estados Unidos?

Pues, por mi hija ahorita sí. Pero si me gustaría algún día regresar a mi país. Este país da muchos oportunidades, la forma de vivir es diferente. Cosa que a veces en mi nuestros países sobre todo el gobierno no nos ayuda en este aspecto. Uno ve mejores posibilidades aquí en este país que en nuestro propio país, hablando en educación, en áreas familiares y todo esto. Tiene sus pros y sus contras.

Translation:

I always say I'm Mexican. That term Latino is used here to differentiate between (people). It's a little racist, in my opinion...When they call you Latina, it's as if they're [saying there is the] United States and then below Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, or wherever. That's how I take it. Really we're all North Americans. In that respect we're all North Americans, whether we're Latinos or Anglos.

It's hard to establish a balance. And harder still when there are children. Why? Because you have to pass your culture to your children so that they will grow with both cultures.

Do you think you'll stay in the United States?

Well, for my daughter, yes. But I would like to one day return to my country. In this country there are many opportunities. The way of life is different. In our countries, the government does not always help us. You see better possibilities here in this country than in our own countries, speaking of education, assistance to families and all that. It has its pros and cons.

Translated by David Cazares

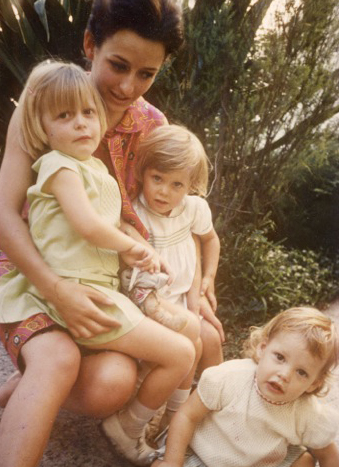

Alexa Horochowski, Minneapolis

Five words: Artist, professor, Sudaca (slang for person from South America), bilingual, resident of the world

I am the daughter of first-generation Argentineans, with grandparents from Spain and the Ukraine, now living in the Midwest. I am a European Latina acculturated to the United States.

My father came to the United States to complete a residency in surgery at the University of Missouri. He was seeking out quality training. My mother joined him for four years and my two older sisters and I were born during this time. When I was still an infant we returned permanently to Argentina. After working in Argentina for 10 years as a surgeon, the dirty war of Argentina prompted my parents to immigrate permanently to the United States in 1974.

I have come to identify more and more as someone from the northern Midwest. When describing my ethnicity I have to include my relationship to Minnesota. I usually think of this relationship in terms of the landscape and winter.

I live mostly in Minnesota, but internally I exist in two worlds. My father lives in Córdoba, Argentina, my mother, in Missouri. I travel to South America about once a year to visit family and have sought out professional contacts as an artist in Buenos Aires. My heritage remains mostly hidden to others, but I am always comparing behaviors I observe in my native culture vs. those in Minnesota. There are positives and negatives on both sides, so it is impossible to decide where one belongs.

When it comes to describing their identities, Latinos in Minnesota use many different terms. The meanings of these terms can change over time and vary depending on the person who uses them.

Hispanic means "of, or pertaining to Spain or Spanish." Hispanic became the term of choice of the U.S. government in the 1970s and appeared on the Census for the first time in 1980 (for more background, read the Hartford Guardian's interview with Grace Flores-Hughes, who helped make this word choice while working for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare).

Latino/Latina means "of, or pertaining to Latin America." Latin America is generally defined as the parts of North, Central and South America where Romance languages are spoken (most often Spanish and Portuguese). This includes Brazil and some of the Caribbean islands. The word Latino was used on the Census (in addition to Hispanic) for the first time in 2000. The question, which was also used on the 2010 Census, was "Is this person of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?" On the Census, race questions are asked separately. You can choose "Hispanic/Latino/Spanish" and also identify as White, Black, American Indian, Asian, or "some other race."

Chicano/Chicana has come to mean Mexican-American, or people of Mexican descent living in the U.S. Popularized in the civil rights movement of the '60s and '70s and by groups like the United Farm Workers, led by Cesar Chavez, the word has political overtones, but is now used more widely.

So even though these words have specific origins and definitions, it is clear that there are as many opinions about the connotations of these words as the number of people you ask. Federico Melo, a Minneapolis resident originally from the Dominican Republic who lived in Boston for many years, sees the difference as regional. In his experience, people on the East Coast prefer Hispanic and people in the west and Midwest prefer Latino. Daisy Terrazas-Cole sees them as interchangeable. "I think of Hispanic being more broad, and Latino/Latina being masculine or feminine."

Other people we heard from prefer to identify with the country their family originally came from. They might call themselves Peruano, Argentinean or Boricua, a term that describes people from Puerto Rico, rather than be lumped in with all people whose roots are from Latin America. And some people we spoke to think of themselves as simply American or Minnesotan.

For Rita Garcia, the words have evolved over time. When she was growing up on the Iron Range in the '50s and '60s Garcia considered herself Mexican. "That was the only word that was used other than derogatory words," she said. "When I went to apply for college I went to the local community college and was showed how to fill out the application. The form said Hispanic. I remember asking, 'I'm Mexican…that's Hispanic?' So I became Hispanic when I applied for college. When I was in college looking for scholarships I then became Chicana. In the '80s and '90s Latino became the generic word. I identify myself as Mexican. For me it becomes interchangeable depending on the circumstance. For some people, it is not. Some people because they don't feel any affinity to the agriculture and the population of migrant workers will never identify as Chicano. For me, it is all of being of that cultural descent. Whatever helps you understand that I am of that population. That is my word of choice."

Daisy Terrazas-Cole, Minneapolis

Five words: Bicultural Latina, wife, sister, daughter, multicultural media expert

Daisy Terrazas-Cole considers herself bicultural and prides herself on being able to navigate many cultures. In fact, it's part of her job as a multicultural media strategist at a Minneapolis advertising agency.

But she wasn't always comfortable in a multicultural world. Terrazas-Cole, 29, grew up in "monocultural" Bell, California, which according to the Census is 93 percent Hispanic/Latino. Her parents, who immigrated to California from Durango, Mexico, in the 1970s, didn't speak English at home, so her first language was Spanish. Her four older siblings, however, exposed her to English at an early age and school introduced her to mainstream American culture. She was the first in her family to graduate from college and when she took a job at the Clinton Foundation in New York in 2006 became the first one to move away from California.

In high school Terrazas-Cole was drawn to music in English, like the Cranberries, Alanis Morisette and the Doors. But finding herself immersed in a totally multicultural city for the first time, found herself listening to more Latin music in New York.

She sees a similar identity evolution playing out with young people in Minnesota - the group of young people who were either born here or came here at a young age, who find themselves translating for their parents and immersed in Latin culture at home, but are in the mainstream culture at school. "You're talking Spanglish, kind of urban, maybe you're a little bit emo, goth or whatever. Really trying to find that identity," she said. "They're still growing up speaking both languages, navigating both cultures. You want to be close to the culture you grew up with but you also want to broaden your horizons."

In New York, Terrazas-Cole met her husband, who is white, and she loves that they can share each other's cultures. "Even though we look opposite - he's tall, blonde and blue-eyed -- we're very similar," she said.

Her husband got a job at the University of Minnesota in 2008 and they found themselves adjusting to a new culture in the Midwest. Minnesota is less diverse than New York, but Terrazas-Cole's first job in Minnesota was as a sales rep for the local Univision affiliate, which quickly introduced her to the state's Latino community. And with Minnesota's relatively large Mexican community she found it was actually easier to find Mexican food products in Minnesota than in New York, which has larger Dominican, Puerto Rican and Cuban populations.

Now she sees her job as a multicultural media strategist as a sign of the times. The retailers she works with - like Ben and Jerry's and Target - see the growing Hispanic population, their buying power and their adaptation of technology and want to reach out to them. That's where her expertise comes into play. "If you want to reach the younger, more bicultural Hispanics - it's about nuance and doing it in a clever way," she said. "You want to message them in a way where they feel welcomed and acknowledged but not so overt that you're excluding everyone else."

Terrazas-Cole sees Hispanics in the United States following a similar path as Italians - they're adapting to American culture, but they're also shaping American culture. American culture is "merging and becoming more diverse and will eventually be more reflective of everyone."

Emilia, Richfield

MPR News is not using Emilia's first name because she is an unauthorized immigrant and fears deportation.

When Emilia first came to the country, she didn't necessarily intend to stay. Her father came to Minnesota from Mexico to make money to send back to his family. "From his work, I was educated, my brother is being educated, my sister graduated. My grandparents had a decent living during their aging years and a humane death," Emilia said. "Something we never could have had if he didn't work here."

Emilia would come to Minnesota as a teenager during the summers to work alongside her father to make money for her private school tuition in Mexico. "I had a hard time being the daughter of a laborer in a private school. I acted out and lost my scholarship," Emilia said. "I came to Minnesota to work when I was 16 years old. He made sure I had the most horrible job in third shift so I learned my lesson."

She came to Minnesota again after graduating high school to make money to pay for college in Mexico, but after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, it became harder to go back and forth. So she stayed. Her tourist visa expired, but she didn't return to Mexico.

Emilia earned her GED and her dad wanted her to find a college in Minnesota to attend. "My dad always knew the importance of education even though he didn't finish elementary school. It was him - not me - who assumed I would go to college," Emilia recalled. However, because of her immigration status, she couldn't find a college that would accept her and or that she could afford because she was ineligible for in-state tuition.

"There wasn't that much conversation about undocumented students in 2001. We existed but it was not as open as it is now," Emilia recalled. "When I was starting college that was the ultimate stigma. In one private college they were really mean. 'She should go back to her country or join a cleaning crew and make a living.' My dad said, 'Don't listen to them. Just keep working hard.' And that was the only advice he could give me. That's still what I hear my dad saying every time I face something that's not easy."

Emilia hasn't given up on her education. She's been attending community college for the last 10 years, taking one or two classes when she could afford it. Emilia hopes to have enough credits to earn her associate's degree after next semester. In the last couple years she's been able to get a few small scholarships from non-profits but she has mostly paid for her school by working as a housecleaner. She also volunteers at community organizations and non-profits.

She's thought about ultimately going to law school, but feels that she can't really make any plans for the future. "The hardest part of being undocumented is my state of mind. Knowing that you can't plan. Human beings tend to live on dreams and hoping for the future," she said.

Emilia often feels frustrated with her lack of options. "Knowing that I'm eloquent and bilingual and I have taken classes and had volunteer opportunities that have given me so much experience and knowledge -- and then I have to scrub toilets. I am very grateful for that job, don't get me wrong, but sometimes my back hurts and sometimes I want to be able to do what I really, really like."

Emilia has been living in the United States without permission for 12 years. She lives in a house in a Minneapolis suburb with her father and partner, who also are unauthorized immigrants. Emilia and her partner gave birth to a child a few years ago and their daughter is a U.S. citizen. "When I got her birth certificate I cried," Emilia said. "I went to City Hall and saw that blue-greenish document with her full name and her social security card. My first generation. My father being undocumented, me and her father being undocumented. Finally, our first generation born here."

Emilia is not eligible for the Obama Administration's deferred action program, which would allow give her authorization to work, or the Minnesota DREAM Act because she didn't attend high school in the United States. Her partner, however, is eligible for the Minnesota DREAM Act. "He can't wait. He already got his transcripts. He already went to see community college and he's excited. It's been a good year so far."

Even though she's uncertain of her future, Emilia is committed to activism. She sees her father aging and knows he won't be able to work for much longer. "We need to let the legislature know that comprehensive immigration reform is needed. Our parents are aging. They deserve an honest retirement, access to health care. We are not legitimate residents of any state, but we pay taxes. I wish people would understand that if we are given the opportunity there's going to be so many individuals who are going to make Minnesota proud and the U.S. proud."

Celso Jimenez, Rochester

Five words: Latino, Hispanic, empleado (employed), indigena Azteca (indigenous Aztec)

Celso Jimenez has lived in Rochester for nearly 14 years and considers it home. He has a wife and a five year-old son and a house where he mows the lawn. But he originally came to the United States to provide a better life for the four children he has in Mexico.

Jimenez works during the day at a dairy farm and at night for a company that cleans office buildings downtown. He has never stopped sending money back to his children in Mexico. His oldest son, now 23, recently graduated from college in Mexico with a degree in engineering. He is now married to a white Minnesotan and together they have a five year-old son. He hopes his son here will stay in touch with his Mexican heritage.

"He's mixed, but I identify him as Mexican American. He needs to know his heritage. Why he's brown. I always tell him he has brothers in Mexico. I've started teaching some Spanish to him for when they meet each other someday," Jimenez said. "He needs to know because there are not so many Hispanic people here and he will put down the Hispanic people because he'll think he's American, but he's not. You're Hispanic. You need to think like a Hispanic. You need to remember you are Hispanic too - not just American."

Even though he's learned to speak English, Jimenez thinks people still treat him poorly because of the color of his skin. "If I were a white Mexican my experience would be different," he said. "When you are Mexican American it's easier. With this color, you're not well-treated."

Jimenez has applied for a visa and hopes to eventually acquire a green card that will allow him to legally live and work in the United States. He crossed the U.S.-Mexico border without permission in 2000 and has been living in the country without authorization since then. He works two or three jobs at a time to support his family here and his children in Mexico. "I'm the head of the house here. I pay it all. I'm paying my taxes. Where's that money come from? From me."

He grew up in Puebla, Mexico where his first language was Nahuatl. His first work in the United States was picking asparagus in California, but the promise of more steady work brought him to Minnesota. He's been married for 10 years, but is applying for residency now because he's worried what would happen if he would be deported.

"My wife doesn't like Mexican food. She doesn't speak any Spanish. She knows some words, but how would she live down there? Who will pay the house here? My mother-in-law - who will take care of her? Rochester is my hometown now."

Interview conducted by Elizabeth Baier.

Armando Oreste Milian Almeida, Bloomington

Cinco palabras: Cubano, hispano, latino, abuelo, padre

Five words: Cuban, Hispanic and Latino. I'm also a grandfather, and father

Vine para acá para Minnesota porque mi hija en un juego que se hace allá en el 2001 escribió a la oficina de interests que es lo que llaman la lotería. Se sacó a la lotería del '98, yo la aprobaron para venir en el 2001. Ella estuvo en Miami como cuatro, cinco dias. A los cuatro, cinco dias subio para aca para Bloomington, para aqui mismo. Ella estuvo trabjando en el hotel Embassy Suites como housekeeping.

Como había aplicado en una escuela, también, en San Luis Park, en la escuela de inmersión de habla hispana en San Luis Park, la mandaron a buscar. Y empieza a trabajar ahi como asistente porque en Cuba ella era licensiada en física y electrónica de enseñanza media.

Yo siempre la dije ella que estaba en la mejor disposición de ayudarla y apoyarla. Ya yo estaba jubilado. Yo me jublié a los 60 años en Cuba. Estuve trabjando durante 40 años y vine para acá para apoyarla y ayudarla. Porque estaba con la niña que había nacido aquí. La iba a cumplir dos años cuando yo llegué. Ella matriculó en la Universidad de St. Thomas que está en St. Paul. Ahí matriculó, le dieron todo una serie de créditos y la carrera la hizo creo que en dos años por la cantidad de créditos y además ella sacó toda una serie de asignaturas.

Su esposo comenzó también a trabajar en hotel limpiando el lobby de abajo. … y tiene un part time en el restaurante porque eso fue lo que él estuvo en Cuba.

Tengo una nieta de siete años que nació aquí cumpla ahora ocho. Está en la escuela. Le ha ido bien.

¿Cómo se identifica, como Cubano o Latino?

Cubano, Latino. Yo soy del criterio que su país natal, sus raices, nunca deben de abandonarse. Al extrema en la casa mi nieta, no se habla inglés porque ya ella tendrá tiempo de aprender el inglés que ya lo habla mejor que yo con su amiguita. Pero las raíces no se pueden perder. Y aquí hemos visto muchos Latinos, muchachos de 16, 17, 18 años hasta estudiando en la universidad que apenas hablan su idioma de raíz mucho menos el escribir porque después el idioma lo pueden aprender en la calle pero el problema es el ortología de escribirlo.

Translation:

I came here to Minnesota because my daughter entered a drawing that we have there (on the island). In 2001 she wrote the U.S. Interests Section (in Havana) in what they call the lottery. (NOTE: The Interest Section allows Cubans on the island to apply for entry to the United States in a lottery that allows only so many in) She won the lottery in '98 and they approved her to come in 2001. She was in Miami four or five days. After four or five days she left for Bloomington, for here. She was working in the Embassy Suites in housekeeping.

She had applied to work in a Spanish immersion school in St.Louis Park and they called her. She began to work there as an assistant because in Cuba she had been a school teacher.

I always told her that I was ready to help and support her. I had already retired. I retired at 60 in Cuba after working 40 years. And I came here to help her. Because she was with her daughter who was born here, who was almost two years old when I arrived. She went to the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul. She began her career after about two years.

Her husband began to work at a hotel, cleaning the lobby and downstairs. And he has a part-time job at a restaurant because that's what he did in Cuba.

I have a seven-year-old granddaughter who was born here. She'll be eight soon. She goes to school.

Do you consider yourself Cuban or Latino?

Cubano, Latino. I'm of the belief that your native country, your roots, you should never abandon. At home, my granddaughter does not speak English because she will have time to learn English, which she already speaks better than me with her friend. You can't lose your roots. And here I've seen that many Latinos, kids of 16, 17 and 18 -- even those in college -- can't even speak the language of their roots much less write it.

Translated by David Cazares

Mary Wint, Mora

Five words: Chicana, sister, mom, abuela, auntie

Mary Wint lives in Mora, Minn., a small town about 70 miles north of the Twin Cities. There are very few people of color where she lives and no Latinos that she knows of. "When I first moved there, I saw a person of color and thought they must be lost," she remembered.

Wint grew up in south Minneapolis. Her mom was a Mexican-American from San Antonio and her father a white Minnesotan. There were not many Latinos in south Minneapolis when she lived there and she was mistaken for Native American, as she still often is living in Northern Minnesota. As a nutritionist for Kanabec and Mille Lacs Counties, she is sometimes mistaken for clients who have come to the county for assistance because of her darker complexion. "People still think of me as an alien even though I was born here," she said.

Wint feels like she lives in two worlds: "the people of color world" and the "white world." Most of her friends are either Latino or Native American and she goes down to the Twin Cities often to see her friends and her daughter. Her daughter, whose father is white, "fits well in the white world and understands it," Wint said.

Wint thinks of herself as Mexican or Chicana rather than Latina or Hispanic. The latter words, she said, "bunch us all together. Even if we all speak Spanish, it's not the same language. The slang and ways of speaking are different."

Olga Zenteno, St. Cloud

Five words: First-generation, creative, attorney, hiker, nature-lover

Olga Zenteno (pictured here with her sister Sian Zenteno) is Bolivian but doesn't know much about Bolivia. She has never been to the country and has never met her many relatives that live there. Her parents, who immigrated to Oklahoma City in 1966, have only been back to their homeland once and didn't often speak of it when Zenteno was growing up. Her parents did teach her Spanish though and she considers herself more Hispanic than Bolivian. Her desire to find her own identity led her to marry a Malaysian-American man at age 21, which estranged her from her parents.

Zenteno moved to St. Cloud in 1995 to clerk for a judge and now works as a legal aid attorney. Now divorced, she is also the sole provider for her sister Sian who came to live with her five years ago and was diagnosed with Asperger's, a form of autism. This only served to reinforce what Zenteno sees as a gulf between the way she sees the world and the way her parents see the world. Zenteno's parents thought her sister Sian wasn't trying hard enough to find a job, while Zenteno saw the difficulty Sian was having and suggested she go through neuropsychological testing. "I don't know if my parents being immigrants understand what autism or Asperger's is," Zenteno said. "I'm pretty sure that they don't. It wasn't labeled as such where they grew up in Bolivia."

A diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes (also known as juvenile diabetes) at the age of 41 inspired Zenteno, now 45, to seek out information about her family history. Her parents wouldn't answer her questions about the disease, so Zenteno sought out information through Facebook from second-cousins and found that her great-uncles had diabetes and had died of the disease.

Worried about what else was hiding in her genes, Zenteno was inspired to have genetic testing. Through 23andMe, Zenteno found that she shared DNA with Native Americans, Southeast Asians and Ashkenazi Jews. The website allows you to connect with others who share similar DNA and Zenteno has been contacted by parents who have adopted children from Guatemala and are trying to find their relatives. This kind of connection reinforces the way she sees her identity.

"I like the broad-based approach to being Hispanic," Zenteno said, rather than just seeing herself as Bolivian. The connection to other Latin Americans through 23andMe, she said, "is tenuous, but it's there. For a lot of people they would say that's not close enough. But for me who has never met any of my relatives, it's significant."

Braulio Carrasco, Minneapolis

Five words: Son, brother, Dominican, immigrant, gay

I became Latino when I came to this country in 2001. I was Dominicano before. I never had to think about my race since all Dominicans are a mix: Negro, Taino y Blanco. It's been an adjustment because even though my mother is white Dominican and my father is Afro Dominican, I am technically biracial in this country. I've had to mark myself down on forms as white, black, other and everything in between. This country has an obsession on race. We don't experience race in the Dominican Republic the same way as we do in the U.S. Especially in Minnesota where at every turn I'm being asked "Where are you from?"

I want Minnesotans to understand that each immigration story is unique and that stereotypes don't flatter (whether I play baseball or dance bachata, etc.) so don't assume. Stop asking "Where are you from?" It's rude. I love Minnesota. For as much I have concerns about living here and there are definite challenges, I love Minnesota because there is still room to grow as a person and make a family. I believe there is diversity in each and everyone of us, so I don't believe in labels, boxes or categories. People are people and we all much more in common than we appreciate or celebrate. We must begin to do so, otherwise we miss out on a lot.

Margarita Sanchez, Minneapolis/Santiago, Chile

Cinco palabras: Voluntaria, escritora, cantante, Latina, madre

Five words: Volunteer, writer, singer, Latina, mother

Mi hija está aquí hace veinte años y yo estoy viniendo hace como 15 años. Ella espera algún día poderme pedir para que yo me quede aquí porque yo allí en mi país estoy sola. No tengo a nadie. Me esposo falleció. Y mi hija quiere que yo esté con ella. Yo estoy viniendo seis meses aca y seis meses en mi país.

En verdad la vivencia de Latinos aquí en los Estados Unidos es… yo creo que es un poca complicada por lo que he visto. Porque cuesta mucho que una persona pueda recibir ayuda. Hay mucha gente que está aquí que no está con sus papeles y tienen miedo de buscar ayuda. Esto yo lo se por mi hija porque ella fue interprete en un hospital, en una clínica. Y llevaba gente y no querían dar su dirección. Pero esta clínica no era mala. Solamente quería ayudarlos. Entonces yo creo que el Latinos aquí en los Estados Unidos tiene unas oportunidades pero hay que saber buscarlas. Porque hay otros que yo he visto me ha tocado porque estoy en una escuela estudiando el inglés, que son flojos. Entonces quieren que todo se lo den. Y no puede ser. Bueno, mi vivencia aquí ha sido muy buena. Yo aprendí aquí a viajar sola en autobús. Aquí me dicen, tú viajas en bús, sola? Sí. Sí, yo ando con mapa y veo el horario de los buses y donde tengo que ir.

Translation:

My daughter has been here 20 years and I have been coming for about 15 years. She hopes to someday apply for me to stay here because I'm alone in my country. I don't have anyone. My husband died. My daughter wants me to be with her. I come here for six months and spend six months in my country.

The truth is that life for Latinos here in the United States is...I think it's a little complicated from what I have seen. Because it takes a lot for a person to receive help. There are many people here who don't have their papers and they are afraid to seek help. I know this because my daughter was an interpreter in a hospital, in a clinic. And there were many people who didn't want to give their address. But the clinic wasn't bad. It only tried to help them. So I think that Latinos here in the United States have some opportunities. But you have to know how to look for them. Because there are others that I've seen, (from what) I gather because I go to school to study English, who are lazy. They want everything to be given to them. And that can't be. But my life here has been very good. I've learned how to travel alone on the bus. Here, they ask me, you ride the bus alone? Yes. I go around with a map and check the bus schedule and go where I need to go.

Translated by David Cazares

Lisette Prendes Moreno, Minneapolis

Five words: Professional, young woman, Ecuadorian, South American, MBA

I am the first person of my family to come to the U.S. I came to do a work and travel program, and went back home to get my bachelor's degree. I came later to get an MBA and I recently graduated and I am currently looking for a job in finance.

I always considered myself only Ecuadorian, it was not until I came to the U.S. where I started to understand that here, people see all the South and Central Americans as a group: Hispanic. I think the term Latina best describes my ethnicity rather than Hispanic.

The Latino community is made up of people with diverse backgrounds and there are many similarities between Americans and Hispanics. I will encourage people to not segregate themselves into groups of only Latinos or any other specific ethnicity, but rather choose members of your network based on values.

Carlos Grados, Minneapolis

Five words: American, Peruvian, husband, father, human

Carlos Grados is proud to have been born and raised in Minneapolis and his family's history in the state starts with a Minnesota icon. "My father came here for additional training as an OB/GYN. After treating Hubert Humphrey's niece, Humphrey sent a letter to the American Embassy in Peru and in three days my mom was able to join my father in Minneapolis," said Grados. "Nine months later I was born."

Growing up, he was not around many other Latinos, but that has changed now that he lives in the Powderhorn neighborhood of Minneapolis near Mercado Central. He doesn't feel like he has a lot in common with the area's predominantly Mexican community -- he doesn't celebrate Cinco de Mayo, for instance -- but he loves being able to pick up tamales in the park, even if they are not quite the same as Peruvian tamales.

The increased diversity of the Twin Cities also means it's easier for him to find the Peruvian foods that used to be nearly impossible to find: chirimoya, Inca Cola, quinoa, and yucca. Teaching high school Spanish has given him an opportunity to introduce his students to the culture of the growing Latino population by using salsa and reggaeton music in the curriculum.

Grados and his wife, a white Wisconsinite, are now raising the next generation of his family in Minnesota. His 10-year-old son Miguel has both sets of grandparents nearby.

Pedro Freyre, Minneapolis

Cinco palabras: Peruano, marketing, MBA, familia multicultural (mi prometida es de Minnesota), híbrido - nací en Perú, pero he vivido en USA la mitad de mi vida

Five words: Peruvian, marketing, MBA, multicultural family (my fiance is Minnesotan), hybrid (born in Peru, but have lived in the U.S. for half of my life

¿Se siente usted como que vive en dos mundos? ¿Por qué o por qué no?

A veces sí y a veces no.... es bonito tener una cultura tan rica como la Peruana y poder hacerle probar a mis amigos y mi novia comida peruana. Lo difícil es que he perdido el sentido de que quiere decir "home" para mí. Cuando viajo a cualquier parte del mundo y regreso a USA siento que regrese "home" excepto cuando viajo a Perú. Viajar a Perú es extraño porque cuando yo siento que Perú ya no es "home" pero cuando regreso a USA siento que USA tampoco es "home". Es raro sentir que uno no pertenece a un lugar específico. A veces es un poquito triste.

Translation:

Do you feel like you live in two worlds? Why or why not?

Sometimes I do, sometimes I don't. It's really nice to have such a rich heritage like my Peruvian heritage and introduce Peruvian dishes to my fiancé, her family and my new friends. What has been difficult to me is to lose the sense of what "home" means to me.

When I come back from an international trip (anywhere in the world except for Peru) I feel like I've come back home. Traveling to Peru is a weird and different experience. When I'm visiting Peru I feel like I'm a tourist and that Lima is not home anymore... and, when I come back to the U.S. from a trip to Peru I feel that the U.S. isn't home either. It's weird to not have a sense of belonging to a specific place. Sometimes it is a little sad.

Translated by Pedro Freyre

Diego Sierra, Maple Grove

Five words: Latino, Ecuadorian, engineer, professional

I am the only member of my family living in Minnesota. I arrived in 2006 with my wife, who is a native Minnesotan and was living in South America at the time. She wanted to be close to her family and we decided to live here.

I am part of a large growing population in the state. Just like native Minnesotans, we bring different academic backgrounds and skill sets. It is important to understand everyone's background and how they can contribute to different aspects of everyday life.

Liliana Orsi, Richfield

Five words: Woman, Argentine, educator, mother, white

Cecilia Martino, Minneapolis

Five words: Latino, female, Argentine, bicultural, multilingual

Liliana Orsi is the mother of Cecilia Martino.

From Liliana:

I came from Argentina at age 52. I am here with my husband and my two daughters. I did not even know I was a Latina or a Hispanic before I came to the U.S. Coming to the U.S. makes you change your perspective and look at yourself in a different light.

I share and "feel" all family events in my home country (through Skype, Facebook, email and phone) -- birthday celebrations, weddings, births, graduations, etc. I often check the weather forecast for Buenos Aires and Twin Cities at the same time. I listen to Argentine radio live and I share my family's worries and challenges when I hear the news in Argentina. I understand what they are going through and I am happy to be here. Some Minnesotans do not realize how fortunate they are!

I would like people to know about people like me, who have followed the legal path to immigration. I want them to know how difficult, long, expensive and painful it is. I hear a lot of talk about undocumented immigrants, but little discussion about the paperwork and complex system that documented immigrants have to go through.

From Cecilia:

We arrived from Argentina in 2001 when I was 18. My mom and I migrated first and later came my sister and dad. We came looking for a better quality of life, mainly due to the instability and the lack of safety in our country. 11 years later, with a B.A., yearly contribution to society (both economic and civic), working at a public school, many dollars spent, and I still don't have permanent status in the country.

At home, I didn't really have to think about identifying myself with a group or ethnicity (granted, I was part of the power system and submerged in white privilege), but ever since I got here all I get asked about (when a little hint of accent comes out) is "What are you?" or "Where are you from?" Being white and having Italian blood does not define my identity. Nowadays I am reminded daily that I don't belong to one group or the other.

I feel like I don't belong here, and don't belong there. People are sure to let you know and remind you with little things every day. Sometimes it makes you proud, sometimes sad. I am bicultural and have a dual identity, which can be very beneficial, but at the same time very confusing and hurtful. I have my own culture, the Argentine culture, which I don't want to let go, but at the same time I want to -- and have to -- adapt to my host culture.

David Pacheco, Minneapolis

Five words: Father, husband, geek, atheist, mixed ethnicity (Latino/European)

I arrived in the U.S. from Costa Rica in late 1990 to go to college. I moved back to Minnesota eight years ago, after living in the UK and Los Angeles for about a decade. I've been stuck here enjoying the winters ever since. I am of mixed parentage, so I have always been seen as slightly different whether living in Costa Rica, the UK or here. I've always considered myself a mutt.

I became a U.S. citizen about 16 months ago, and it was a very cool moment. I believe the U.S. Constitution is one of the most amazing government creation documents in history. The story of its creation, and how it has survived by allowing itself to be interpreted by the context of its time, will always be fascinating to me. Seeing the Constitution and the Bill of Rights at the National Archives last year soon after I became a citizen was one of the highlights of my life.

Dolores Montes, Minneapolis

Cinco palabras: Latina, Mexicana, trabajadora, amorosa, honesto

Five words: Latina, Mexicana, hard worker, loving, honest

Llego a Minnesota en 2006. Soy madre de tres hijos. Mi hijo mas grande tiene 10 años. La otra tiene cinco y la más chiquita tiene tres.

Ahora siento que es como es mi país porque...me gusta más aquí Estados Unidos que México. Porque digo como es posible que aquí siendo otro país tenemos más ayuda porque no nos quedamos sin comer. Si no tiene mi esposo muchos ingresos no nos quedamos sin comer porque muchas ayudas en donde podemos recurrir a buscar alimientos cosa que en nuestro país no tenemos. Me siento más protegida por la policía porque se que la policía no es corrupta como en mi país. Me gusta mucho este país.

Mi hijo de 10 años él me dice, "Mami, yo no soy Mexicano, yo soy Americano. Y él es Mexicano. Pero él dice que "yo soy de los Estados Unidos. Yo soy Americano." Él dice que como me lo traje de dos años y ocho meses él no conoce a México. Entonces yo digo, "Tu eres Mexicano." Y me dice, "Sí, pero yo amo a Minnesota. Yo no me quiero regresar a México."

Y ahora mi hijo nos sirve de interprete porque el sabe más inglés que nosotros.

Translation:

I came to Minnesota in 2006. I have three children. My oldest son is ten years old, my older daughter is five and my youngest daughter is three.

Now I feel like it's my country. I like the United States more than Mexico. Because, I mean, how is it that here in another country we have more help, that we don't go hungry. If my husband doesn't have much money we don't go hungry because there is a lot of help, places where we can go to find food, something that we don't have in our country. I feel more protected by the police here because the police are not corrupt like in my country. I like this country.

Yes. My 10-year-old son tells me, "Mami I'm not Mexican, I'm American." And he is Mexican. But he says, "I'm from the United States. I'm American." He says that since I brought him here when he was two years and eight months he doesn't know Mexico. But I tell him, you're Mexican. And he says, "Yes, but I love Minnesota. I don't want to go back to Mexico."

Now my son serves as our interpreter because he knows more English than we do.

Translated by David Cazares

Abel Solorzano, Golden Valley

Five words: Chicano, American, second-generation, son and uncle

I was born in California to immigrant parents and during my youth I lived in Northern California's central valley. There were many children like me, either born in Mexico or have Mexican immigrant parents. I only heard terms like Mexican-American, Latino and Hispanic because of standardized tests or government forms. I didn't think much of ethnic and racial diversity.

When my family relocated to Arizona for my teenage years, we lived about 30 minutes from the southern border with Mexico. The population was majority Hispanic. I started seeing different treatments among racial groups. I even started seeing it within the Hispanic group which was comprised mostly of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. I started to use Mexican-American to identify myself throughout my junior high and high school years.

I relocated to the Twin Cities to start my career in the engineering profession. Every Hispanic professional I've met is from another country and are here on work visas. To differentiate myself from them I say I'm Chicano because that states I have both Mexican and American cultural influences.

Amalia Moreno-Damgaard, Eden Prairie

Amalia Moreno-Damgaard first came to the United States to get her undergraduate degree. She liked it so she stayed to get her master's degree and took a job in international banking when she graduated, living in Kansas City and St. Louis.

Her life in Minnesota began when her husband got a promotion and relocated to the state with Amalia and their young son in 2001. Around the same time, Amalia had decided to make a drastic career change: from the financial world to the culinary one. She wanted a more flexible career while she was raising her son and chose to follow her passion for food and cooking.

She started with her native Guatemalan cuisine, but soon branched out to studying other Central American cuisines and then eventually many other Latin American styles of cooking. She currently has her own catering business and recently published a cookbook.

"I consider myself multicultural because of what I focus on: Latin American cuisine," she said. "Guatemalan cuisine is very ancient -- it dates back to the ancient Mayan civilization, with the influence of the Spanish. I like to learn more about other Latin cultures. I say that I have a foot in the states and a foot everywhere else."

Her husband is from Denmark and she considers her son 'tri-cultural" -- Danish, Guatemalan and American. He attends the international school and the family's diverse circle is very different than when they first moved to Minnesota.

"When I moved to the Twin Cities about 12 years ago, it was very rare to see a Latino in the Minneapolis area," she remembered. Moreno-Damgaard is glad to see the state becoming more diverse and to see the Latino community growing. A bonus: more access to Latin American foods in the Twin Cities.

While she primarily thinks of herself as a Guatemalan-American, she also identifies with the larger Latino community.

"I like to use the word Latino. I like to use the word Latin American as well," she said. "It creates some sort of a bond -- some sort of a sisterhood or brotherhood when you call yourself Latin American and you are in a group of Latin Americans. Not all Latinos from Latin America are the same. They come from all the races and many ethnicities and I think that may be part of the reason that people are confused about who we Latinos are."

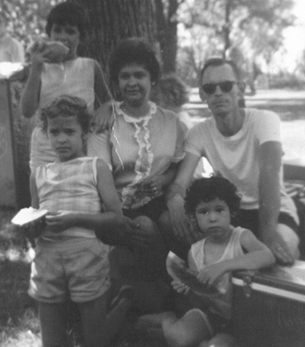

Maria Regan Gonzalez, Minneapolis

Five words: Chicana, young professional, health equity advocate

My parents met in Mexico City in the early 1980s. At the time, my father was a young powder metals engineer, one of five children from an Irish-Swedish immigrant family, born and raised on a small dairy farm in Mora, Minn. He had taken his first big job with a metals company in Mexico City and was embarking on a new adventure, not knowing one bit of Spanish. My mother, a young secretary at a law firm in Mexico City, was an aspiring college student who had to drop out to support her father and nine other siblings living in the poor district of Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl. Her mother had died when she was only 13 years old.

At home I grew up speaking Spanish, eating my mother's Mexican food and taking regular family trips to Mexico to visit my aunts and uncles. My younger brother and I were raised in a very traditional home, going to a Catholic school and church. Starting at a young age, it was my responsibility to help my mom with the daily tasks of the home. On the weekends we'd attend the quince años, weddings and baptisms of friends.

While my family life was very influenced by my mother's culture, I was also very impacted by Midwestern American culture, growing up in Wisconsin. My brother and I attended an all-white school where our family was the only multicultural family in the entire school. Neither of us wanted to take the food our mother prepared for school lunch since we were embarrassed by not having the standard peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and carrot sticks. In middle school, this rejection of my culture continued. I refused to go by my first name, María, named after my Mexican grandmother. I decided to only respond to my middle name, Mackenzie. I didn't want to be different, I wanted to blend in. My friends also denied my Mexican identity. Looking back on these years, it seems all quite silly, but it was the way that I dealt with my two cultures as a kid.

Then in high school and college I began to explore my biracial identity and traveled a long and confusing journey from feeling like having no identity to accepting a sometimes contradictory identity as a Chicana. I had a difficult time figuring out who I was. Growing up as a Midwestern Chicana, I took summer trips up north to the cabin, played ice hockey, spoke Spanglish at home and took frequent trips to Mexico to visit family. I didn't feel like the term Latina, white or caucasian fit me well. In college, I learned about the term Chicana and I identified with it right away. I don't feel 100 percent white nor 100 percent Mexican, I feel like a mix of both cultures.

Going through a journey of self-exploration over the years, I've learned that my identity has given me the ability to act as a cultural bridge builder. I've also learned that I feel most comfortable in the 'in between spaces' and no longer fear them. Now in my professional life, I use this role as a bridge builder to foster collaborative relationships between community members and local government and decision makers to promote health and reduce chronic disease. I hope to continue my work in this arena and act as conduit for the development of policies and systems that are informed by the communities that are impacted by them.

Matias Araya, Brooklyn Center

Five words: Chilean, hard working, dad, husband, friendly

The way I describe myself has changed over this five years I've lived here in a more inclusive way. Before moving to the United States I considered myself just Chilean, but in my first year here I become more aware of how people see Central and South America, and my experience knowing and meeting Latinos from different countries. I now identify as Latino.

I came here to marry an American citizen in 2008. I have been living here in Minneapolis without any family members, so my family here are my wife and daughter. I came here with little English, I took some classes in college in Chile. I took ESL classes for eight months here until I got better in English, and was able to work. I went to a community college and kept working, then I transferred to the University of Minnesota where I graduated and now I work in human resources. I am the first and maybe the only one of my family to emigrate out of Chile as well the only of my siblings to attend college.

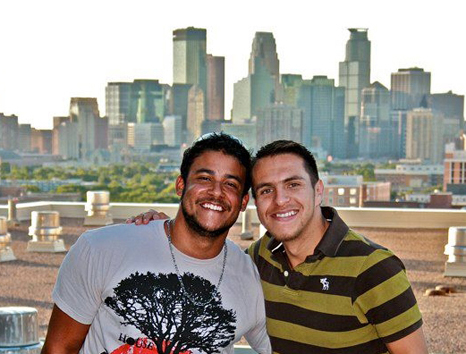

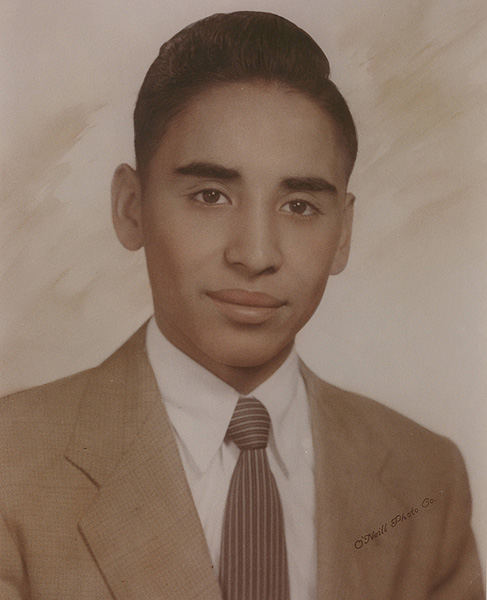

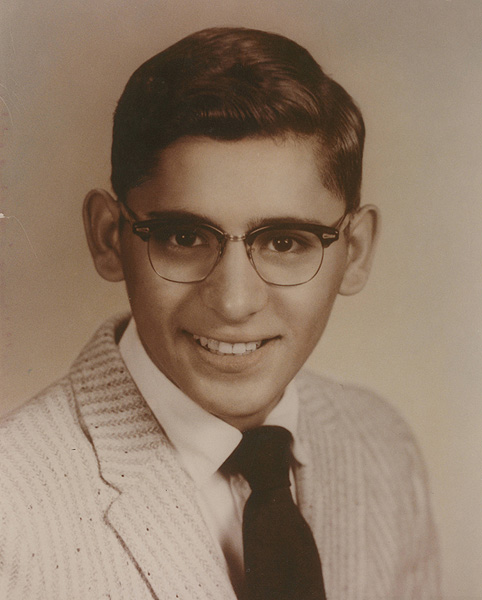

Alfonso Wenker, St. Paul

Five words: Gay, Latino, nonprofit geek, activist, brother and friend

Alfonso Wenker feels at home on the St. Paul's West Side. As he walks around the neighborhood he'll regularly run into a cousin, an aunt, an uncle or a family friend. His mom and her eight siblings were born and raised there and all of them continue to live in the neighborhood or nearby. His uncle Joe still lives in the house they all grew up in.

The West Side has been the heart of the Latino community in St. Paul since around World War I, when Mexican-Americans came to the area to work in meat packing plants and sugar beet fields. Wenker's great-grandfather was part of this first wave of Latino migration to Minnesota. He was a migrant farm worker and he followed the crops back and forth between Texas and Minnesota, where he eventually settled on the West Side Flats. His grandfather Francisco Lucio was born in St. Paul in 1918.

With deep family roots in the city, Wenker considers himself a St. Paulite more than anything else. "Growing up, Latino wasn't really part of the vernacular," he said. "We described ourselves as Mexicans and we knew what that meant in our community and family. As I got older and I started to branch out outside the neighborhood I grew up in I understood that there are political implications for how we talked about ourselves."

His mother never learned to speak Spanish and as a result couldn't pass the language on to her children. But, he made an effort to study Spanish in high school and college and was a Spanish minor at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul. "There was a desire to fit in and not stand out too much among my grandparent's generation," Wenker said.

In college, he started to get involved with activism with the LGBT community and has since worked for Minnesotans United for All Families and the PFund Foundation. Wenker came out to his family in his late-teens and feels lucky that they've been so accepting.

Wenker is disappointed, however, that there aren't more spaces where he can express his full identity. He said people in the Latino and LGBT communities rarely mix. Wenker has been able to create a circle of family and friends who can express the multiple facets of their identities together, but he sees a change that needs to happen.

"The natural evolution of the demographic shift in our state and in our country is going to require social spaces, cultural spaces, public policy approaches that will require us to look at those multiple identities," said Wenker, who now works at the Bush Foundation in St. Paul. "Slowly but surely there are people who are creating those communities for themselves."

The different identities at play reinforces Wenker's view that there is no "one perspective" of the Latino community. "Mine is only one story and it's a particular kind of story that's about a family that's been in Minnesota for a very, very long time," he said.

"Part of that story is about cultural assimilation and what happens to communities when we feel like we have to shed part of who we are in order to fit in or thrive. My hope in sharing that is that we can think about ways to build our communities so folks don't feel like they have to check part of themselves at the door in order to thrive or survive."

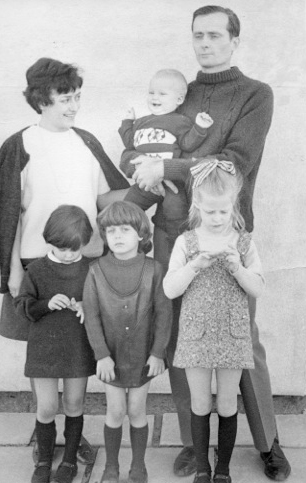

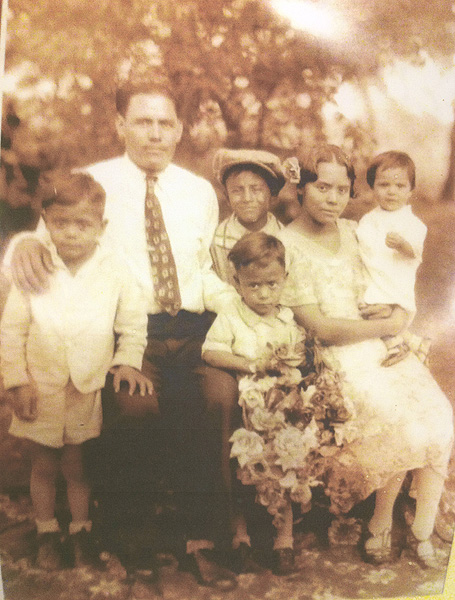

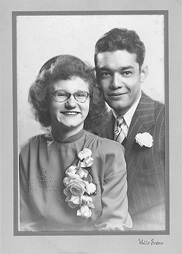

The Hernandez Family

Sam Hernandez, 83, Stillwater

Beatrice Diaz, 80, Fairmont

Frank Hernandez, 75, Janesville, Wis.

Chris Hernandez, 72, Fairmont

Emily Diaz-Torres, 68, Macomb, Mich.

The surviving Hernandez siblings recently gathered in Sam's Stillwater home to celebrate the 80th birthday of their sister Beatrice, who is credited with keeping the family together in a time of crisis.

Their parents were migrant workers who travelled from Mexico to Arizona to California to Oregon to Minnesota to Michigan, following the crop harvest and factory production cycles, taking their young children with them. Isidore, now deceased, was born in 1927, followed by Linus, also deceased, in 1929 and Sam in 1930. In 1941, the family was hired by the Verdoorns, a farming family that grew and trucked potatoes, onions and other lowland produce. This allowed them to stop migrating around the country and settle in Delavan, which had a population of 822 as of the 1950 U.S. Census. Sam's mother told him that by the time he started sixth grade in Delavan, he had attended over 40 different schools.

But even though they were settled, the children still worked in the fields until harvesting was done, sometimes not starting school until October or November, leaving them with weeks of school work to catch up with. All of the Hernandez siblings recall working in the fields, topping onions and weeding. They remember their father dropping them off at the fields, unsure what he did all day. Sam describes their father as a "born hustler," a man who would find work for other migrant families and figure out a way to make a little cash in the off-season. When Sam and his brother Linus were young, this meant finding places for them to play music, Sam on violin and Linus on guitar. Sam and Linus later played in jazz combos together as adults, Sam on trombone and Linus on trumpet.

Beatrice, born in 1933, was the bridge between her older brothers and her younger siblings. Her older brothers had left home by the time their father died in 1951 and her mother didn't speak English and was not able to make enough to support the family from the fieldwork that she did. Bea, who had recently graduated high school as valedictorian, was left with a choice: accept a full scholarship to attend college, or become the primary breadwinner for her family and keep her siblings out of foster care. She chose the latter.

Bea had already been working to support the family while in school. Before he died, their father had contracted tuberculosis and spent several years in the Ah-Gwa-Ching Sanatorium in Northern Minnesota. Bea took a job as a phone operator and then worked at the Interstate Power Company when the family moved to Winnebago in 1952 to be closer to their maternal grandmother. Frank, who was still in school, also helped to raise the two youngest siblings, Chris and Emily.

Bea eventually got married and had three children of her own, while her siblings achieved professional success. Sam and Isidore attended college on the G.I. Bill and both became teachers -- Sam in St. Paul and Isidore in Mexico. Sam later worked as a consultant on diversity issues and Isidore founded his own school.

Frank finished two years of college and then joined the Minnesota Highway Department and later went to work in human resources at two large insurance companies.

Chris became ordained as a priest and was consecrated as an Archbishop. He was also a teacher, living in California until he recently retired.

Emily, who dropped out of school, was married and had her first child at 14, moved to Michigan and started working at the Ford Motor Company at age 18. She had three other children while working her way up from production worker to a quality engineer. She finished her career as an international auditor in Mexico for Ford, which paid for her to get her college degree. Now retired in Michigan, she is the volunteer executive director of a non-profit that works with immigrants.

The siblings credit their own self-motivation and the small town of Delavan for making sure they went to school and setting them up for success. They never felt treated any differently because of their ethnicity. "I didn't know I wasn't Scandinavian until I went to California," remembered Chris. Emily agreed, "I went to Michigan and realized there were different cultures. I always had thought I was just American just like everybody else I grew up with." They were the only Mexican family in the Delavan schools, but the teachers and community held the Hernandez siblings to the same standards as any other student, even if they missed school because of work. "We ended up in a bitty town that didn't give us any sense of difference. We just kept on trucking like everybody else in town. We made it because of that little town," Sam said.

But Sam was quick to point out that even though the town was accepting, there were lines that simply weren't crossed -- like when it came to marriage. Frank, Bea and Emily all married siblings from the Diaz family, the only other Latino family in town.

But Bea and Frank don't identify as Latino or Hispanic. "I just consider myself an American," said Frank. Bea agreed, "I never thought of myself as different. I've never been racially harassed. Everything's always gone alright. I'm an American, a Minnesotan. Been very lucky." Sam, on the other hand, through his work in education and diversity sees himself as a Chicano. "White America doesn't consider me American. As long as they call me a Mexican-American, I know that they don't consider me American."

Emily's views on her own identity have evolved. "I had to learn to become a Hispanic," she said. "When I got to Michigan, I was white. I used to refer to Latinos as 'them.' Now I work with Hispanic families. I have realized I am 'them.' But there's also a difference between them and me. There are very many injustices that befall us -- and I am part of that 'us.' But there will always be that part of me that is truly American. The people that are coming into this country have to get that. That's what I do. I teach citizenship and I teach them to be proud of this country, because it's a wonderful country. They're learning it. It's in me."

Luis Del Aguila, Faribault

In the last 10 years, Luis Del Aguila has held many jobs, from mailman to mortgage originator, from car-washer to small business owner. As a newcomer to the United States, he is always looking for opportunities.

Del Aguila, of Faribault, Minnesota, owns the multi-purpose business Anadelas on Main Street, which sells clothes and shoes and offers a variety of financial services. His motto: adaptation.

A native of Guatemala, Del Aguila moved to the United States in 2003 when his son was only 6 years old. He spent 11 months in Los Angeles before moving to Faribault, where his sister-and-law's family lives.

He and his wife became U.S. citizens last year.

For Del Aguila, a big part of adapting to a new country means diversifying his business. He sells dresses on racks and shoes on tables that are visible from the shop window. On the counter in the back are two machines for wiring money internationally. Behind the counter there's a table for clothing alterations and a shelf with books dedicated to tax filing and number crunching. His business has expanded to accommodate local customer demands.

In Guatemala, where Del Aguila earned a bachelor's degree in business administration, he specialized in finances and was manager of a branch for a private financial company. During a tough period in Guatemala's economy, Del Aguila lost his job and his family made the decision to move to the United States.

Like many immigrants, he discovered upon arrival to the United States, that his degree in Guatemala means little. His first job in the United States was as a parking lot attendant in Los Angeles.

While Del Aguila may have been overqualified for most of his jobs in recent years, he still greatly values higher education. He passed this value on to his 16-year-old son, Christian. This fall, Christian will attend the boarding school Perpich Center for Arts Education.

Along with adapting to new work, Del Aguila and his family have had to adapt to a new culture. He said that for him and many other immigrants, the major obstacle isn't racism, but the fear of the unknown. Although he speaks sufficient English to meet his daily needs, he switched to Spanish in a recent interview to better express himself.

"We don't like the unknown, we are repelled by what we don't know," Del Aguila said. "There are opportunities for everyone, there is work for everyone. We are a big country, and there's a lot to do. So I think it is purely about adapting and learning how to coexist, to mutually respect different cultures, and to keep the good and push aside the bad habits that we all have."

Del Aguila recalls feeling uncomfortable and fearful in Guatemala when he saw people very different from him. In the United States, he knows that some people may be wary of him because he is an immigrant. This time, he is the one who is unknown, who is different. That, he said, makes it hard for him to make connections in the United States -- a land of opportunities, but also a land of networking.

Keeping in mind cultural obstacles, Del Aguila makes his goals both challenging and realistic. He emphasizes that his achievements are only made possible by hard work and, of course, adapting.

"I adjust to my reality, I adjust to what I know I can do, what I can develop," he said. "I'm not a person of big dreams that are out of the realm of possibility, right?

"I can't think 'I want to be the next Carlos Slim,' " he said, a reference to the Mexican telecom mogul. "Carlos Slim -- I can't, no, no, no, that's not my plan. I just adapt. To what is, to what I have, to what I can. I've only adapted."

Written by Silvia Foster-Frau

Beatriz Castro, Moorhead

Five words: Latina, student, feminist, activist, daughter

The thing Beatriz Castro misses most about her hometown of Madelia? The pupusas. Pupusas, tortillas stuffed with fillings and fried, may not evoke images of small-town Minnesota to some, but Madelia is a small town in southern Minnesota, home to Tony Downs Foods and a growing Latino population. In 1990, Latinos made up about nine percent of the town's population. In 2010, they accounted for 27 percent.

Beatriz's mother came to Minnesota in the late 1980s to escape civil war in El Salvador and found work at Tony Downs. Beatriz grew up in the small town and in school realized there were two different ways of looking at the world: one learned from her family and one from school. After high school, Beatriz chose to continue her education and she expects to earn her bachelor's degree next year from Minnesota State University Moorhead. She is interested in anthropology and gender studies and is working in the gender studies office this summer.

Being around a more diverse population in Moorhead has made her embrace the uniqueness of her own background. "I am Minnesotan as much as the next person but I am also a Central American. I can be both -- and I am proud to be both."

Magaly Cambara, Minneapolis

Cinco palabras: Cubano, madre, abuela, Latina, Hispana

Five words: Cuban, mother, grandmother, Latina, Hispanic

¿Porqué salió de Cuba?

Porque yo tengo una hija que vive aquí hace 11 años y ella me reclamó. Estoy aquí. Y mi hija me reclama a mí y entonces yo pedí para (mi otra hija). Entonces al año de yo venir vino mi hija con el niño. Estamos aquí los cuatro.

Es un poco diferente a la cultura de Cuba. Todo ha sido distinto. Para uno acostumbrarse no es tan fácil. Mi hija que lleva 11 años, ella está adaptada aquí. Pero yo. No es muy fácil adaptarse aquí. Porque otra cultura. Yo no hablo inglés. No tengo amistades americanos porque no puedo expresarme. Y por eso es difícil. Pero me siento bien. Estoy con mi familia.

El niño está aprendiendo inglés. Y me dice a mí, "Abuela. Tu lleva tanto tiempo aquí, tu no habla inglés. Y yo hace poquito que llegué yo hablo inglés." Y me dice las cosas. El me enseña. A veces el me enseña. Y tengo que repetirlo varias veces para que yo lo diga bien.

Translation:

Why did you leave Cuba?

Because I have a daughter who has lived here 11 years and she sponsored me. And then I asked my other daughter to come. A year after I came my (other) daughter came with her son. The four of us are here.

It's a little different than the culture in Cuba. Everything has been a change. It's not easy to adapt. My daughter has been here 11 years (and) she's adapted here. But me. It's not very easy to adapt here. Because it's another culture. I don't speak English. I don't have American friends because I can't express myself. Because of that it's difficult. But I feel good. I'm with family.

My grandson is learning English. And he tells me, "Grandmother, you've been here so long and you don't speak English. And I've been here just a short while and I speak English." He tells me things. He teaches me. And I have to repeat it various times to make sure I say it well.

Translated by David Cazares

Aureliano DeSoto, Minneapolis

Five words: Chicano, intellectual, professor, gay, Californian

I think I've always had a strong sense of myself culturally as Mexican American, born within a family that had widely differing racial and ethnic self-conceptions of itself (New Mexican, Español, white) that were intertwined with the racial politics of the United States, assimilation, and intermarriage with Anglos (white Americans). It wasn't until I went to college that I was able to better describe the racial and ethnic politics of both my family and myself. It was at that time that I adopted the term "chicano" as a self-descriptor, one I have maintained ever since, although arguably the concept of chicana/o itself is a moving target, subject to constant transformation and change.

Even though I have a rich professional and personal life in Minneapolis, and consider myself a Minnesotan, I don't "make sense" culturally in Minnesota, insofar as my particular background and cultural standpoint is determined by a Californian Mexican-American worldview. By this I mean the experience and perspective of Mexican peoples of historical long-standing in the United States, who are English-dominant (i.e., mostly use English in their personal and professional lives), are for the most part culturally and socially assimilated, have abstract relationships to contemporary immigration, are partnered or intermarried with other Americans (of any race), who self-identify principally as American, and whose demographics can support identifiable community institutions along with specific residential and commercial zones/neighborhoods/barrios. I find this Mexican American sensibility is missing here, and I often feel bifurcated between the places where I can be "recognized" (as a functionally assimilated gay chicano professional who is English-dominant) such as California, and my home in Minnesota, where I am most often just assumed to be white in my daily life, even (or maybe especially) by other latinas/os.

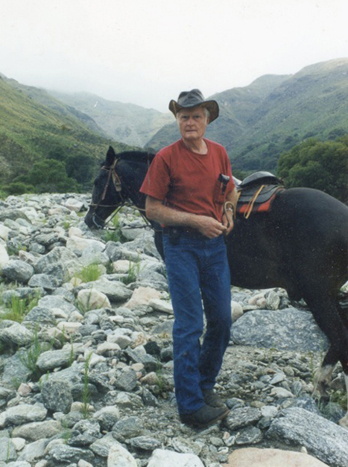

Rita Garcia, Lake Elmo

Five words: Latina, community activist, entrepreneur, businesswoman, change agent

Rita Garcia's story begins with her father's decision to come to Minnesota.

After her mother and father met and fell in love in Grand Rapids, Minn., they raised their family in Virginia, Minn.

There were no other Mexican families nearby, so their father, Dave Garcia, did his best to make sure his children learned about Mexican culture.

Even though many of her friends' parents and grandparents were immigrants, Garcia faced prejudice growing up, but found acceptance through girl scouts and athletics.

After dealing with periods of unemployment working in the iron mine, Garcia's parents became small business owners.

Garcia moved away from the Iron Range to attend college in Duluth. She eventually transferred to Mankato State University because they offered women's athletic education classes.

Her first job was as a student teacher on St. Paul's West Side. She taught physical education.

When Garcia was a senior in college her mother died and her younger sister, who was in junior high school at the time, came to live with her. Garcia was unable to find steady employment as a physical education teacher and decided to switch careers.

Working at Xerox, Garcia worked her way up from a repair technician to a vice president. Even though she was able to find success, she still sees many things that need to change.

The way Garcia has identified herself over time, reflects the shifts that have taken place in the population of the United States.

About the project

The demographics of Minnesota are changing and the growing Latino community is an important part of that change. The first wave of Latino migration to Minnesota began in the early 1900s, when migrant workers from Mexico would came to the state to work in factories and in farm fields. Some of these workers moved on, but some stayed, many settling on St. Paul's West Side.

More recently, Latinos have been the fastest growing group in Minnesota for the past decade, establishing thriving communities throughout the Twin Cities metro area and in greater Minnesota. As of July 2012, the Latino population had grown by 85 percent since 2000 to a total of 264,359, according to U.S. Census data. Looking at the youngest generation the trend seems likely to continue. Latinos make up 8.3 percent of Minnesotans under 18, making Latinos the largest minority group in that age group.

This project aims to tell the stories of Latinos in Minnesota, delving deeply into how they define their own identities and how they relate to the larger Latino community in the state. Through the Public Insight Network, MPR News collected the stories of over 125 people who trace their roots back to 17 different countries. Some of the respondents' families have been in Minnesota for generations, while others have arrived in the past few years. Some came to the state as migrant workers, others as professionals.Their stories make it clear that there is not a universal take on what it means to be Latino -- or Hispanic or Chicano -- in Minnesota. But the stories do have one thing in common: Whether the respondents or their ancestors came to the state for work, love, or education, Minnesota is now home.