Timeline: Mental illness and war through history

Doctors used to call it "shell shock," "soldier's heart," or "nostalgia." Soldiers would shake uncontrollably, experience heart palpitations, or go blind after witnessing trauma on the battlefield. From as far back as ancient Greece, history reveals the psychological toll of war on soldiers. Today we call the condition post-traumatic stress disorder. Click on the dates in the right column to advance the timeline.

490 B.C: A soldier goes blind "without blow of sword"

A marble sculpture from 420 B.C. depicts a battle between Greek and Persian soldiers, possibly the Battle of Marathon. (The British Museum)

The Greek historian Herodotus describes an Athenian warrior who became blind when a soldier standing next to him was killed during the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.

"A strange prodigy likewise happened at this fight. Epizelus, the son of Cuphagoras, an Athenian, was in the thick of the fray, and behaving himself as a brave man should, when suddenly he was stricken with blindness, without blow of sword or dart; and this blindness continued thenceforth during the whole of his after life," Herodotus wrote.

"The following is the account which he himself, as I have heard, gave of the matter: he said that a gigantic warrior, with a huge beard, which shaded all his shield, stood over against him; but the ghostly semblance passed him by, and slew the man at his side. Such, as I understand, was the tale which Epizelus told."

1678: "Broken" soldiers long to return home

First battle of Villmergen (1656) in Switzerland, depicted by an unknown 18th century artist (Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Johannes Hofer, a Swiss physician, coins the term "nostalgia" to refer to cases of homesickness, a condition that afflicted Swiss troops stationed far from home.

Around the same time, German and French doctors also diagnosed the condition as homesickness ("heimweh" and "maladie du pays"), as they believed the symptoms came from a soldier's longing to return home. Spanish doctors called it "estar roto," literally, "to be broken."

"Nostalgia" remained a common mental illness for the next 200 years.

1761: A disease called "nostalgia" torments soldiers

Austrian physician Josef Leopold Auenbrugger describes the plight of trauma-stricken soldiers, in his book "Inventum Novum."

"When young men who are still growing are forced to enter military service and thus lose all hope of returning safe and sound to their beloved homeland, they become sad, taciturn, listless, solitary, musing, full of sighs and moans. Finally, these cease to pay attention and become indifferent to everything which the maintenance of life requires of them. This disease is called nostalgia. Neither medicaments, nor arguments, nor promises, nor threats of punishment are able to produce any improvement."

Josef Leopold Auenbrugger, a noted Austrian physician, in an undated portrait. (Wikimedia Commons)

Civil War: "Soldier's heart" afflicts troops

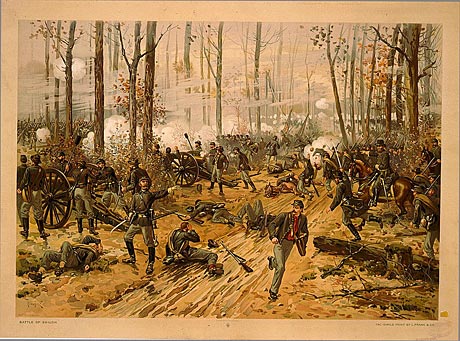

The Battle of Shiloh, as depicted by the artist Thure de Thulstrup in 1888. (U.S. Library of Congress)

The brutal battles of the Civil War triggered widespread psychiatric trauma among the troops. Thousands of soldiers were stricken with the psychiatric condition known as nostalgia, making the disorder the second most common diagnosis made by Union doctors in the 1860s. Physicians also created several new terms, including "soldier's heart" and "exhausted heart," to describe the experiences of emotionally distraught soldiers. Symptoms included sudden mood changes, heart palpitations, self-inflicted injuries, paralysis, tremors, and a longing to return home.

Noted author Ambrose Bierce wrote that he was plagued "by visions of the dead and dying" many years after the war ended. Bierce fought as a Union soldier in the Battle of Shiloh, an intense two-day fight that killed more than 23,000 men.

Noted author Ambrose Bierce wrote that he was plagued "by visions of the dead and dying" many years after the war ended. Bierce fought as a Union soldier in the Battle of Shiloh, an intense two-day fight that killed more than 23,000 men.

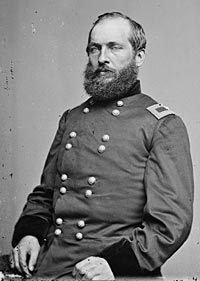

The war also forever changed Union general and future U.S. President James Garfield. "At the sight of these dead men whom other men had killed, something went out of him, the habit of a lifetime, that never came back again: The sense of the sacredness of life and the impossibility of destroying it," wrote 19th century author William Dean Howells of Garfield.

James Garfield, Civil War general and future president, in a photo taken between 1855 and 1865. (U.S. Library of Congress)

World War I: "Shell shock" hits the trenches

Wounded British soldiers in a trench during World War I. (Library of Congress)

Military physicians started using the terms "shell shock" and "combat fatigue" to describe soldiers' reactions to trauma in the early years of World War I. Victims appeared detached from daily life, suffered amnesia, developed a peculiar gait, and became blind or deaf.

"Shell Shock! Do they know what it means? Men become like weak children, crying and waving their arms madly, clinging to the nearest man and praying not to be left alone," one man wrote in his journal, in the middle of the vicious Battle of the Somme in 1916.

At first, the military believed that shell shock was a physical reaction to shelling, an actual "shock" to the nervous system. But when soldiers who never experienced shelling started reporting the same symptoms, physicians began to classify the condition as a psychiatric disorder.

French infantry firing from a trench during World War I. (Library of Congress)

"I wish you could be here in this orgie of neuroses and psychoses and gaits and paralyses," a professor of medicine at Oxford wrote to a colleague in 1915. "I cannot imagine what has got into the central nervous symptom of the men...Hysterical dumbness, deafness, blindness, anaesthesia galore. I suppose it was the shock and the strain, but I wonder if it was ever thus in previous wars?"

Reporters struggled to explain the bizarre and wide-ranging symptoms. "The soldier, having passed into this state of lessened control, becomes a prey to his primitive instincts," the Times reported in 1915. "He may be so affected that changes occur in his sense perceptions; he may become blind or deaf or lose the sense of smell or taste. He is cut off from his normal self and the associations that go to make up that self. Like a carriage which has lost its driver, he is liable to all manner of accidents. At night insomnia troubles him, and such sleep as he gets is full of visions; past experiences on the battlefield are recalled vividly; the will that can brace a man against fear is lacking."

World War II: Long deployments cause "battle fatigue"

A Marine returns after two days of battle on the beaches of the Marshall Islands in February 1944. (U.S. National Archives)

British and American physicians use the terms "battle fatigue," "combat fatigue," and "gross stress reaction" to describe traumatic responses to combat during World War II. As the terms imply, the military believed that the condition was partly related to long deployments.

Historian Ben Shephard describes one British soldier's emotional breakdown. The soldier collapsed and lost the ability to speak after he saw his best friend's body blown apart by a landmine. He was transferred to a psychiatric hospital in Cairo, where a general described him as "tremulous, dazed, tearful, show[ing] the startle reflex." Many of his fellow patients "had severe battle dreams and were restless and inclined to scream in their sleep." The soldier returned to active duty 49 days later. After the war ended, his wife told a doctor that her husband was "well employed but inclined to rush out of doors when the children are noisy."

"I sometimes get in a mood that I want to kill myself or somebody who has said something I dislike. It has only been since I came back from the front line. My life before I came into the army was uneventful but full of childish dreams," recounted one British soldier after being evacuated to a psychiatric hospital.

The 1946 U.S. Army-funded documentary "Let There Be Light" follows 75 "psycho-neurotic" soldiers being treated at a psychiatric hospital. Upon review, the military banned the film. It was not declassified until 1980.

As the camera pans across a group of soldiers, the narrator solemnly announces: "These are the casualties of the spirit, the troubled in mind, men who are damaged emotionally. Born and bred in peace, educated to hate war, they were overnight plunged into sudden and terrible situations. Every man has his breaking point, and these, in the fulfillment of their duties as soldiers, were forced beyond the limit of human endurance."

1952: "Gross stress reaction" becomes official

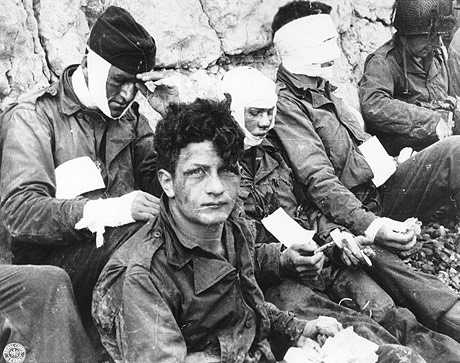

Casualties on Omaha Beach. (U.S. National Archives)

In the aftermath of World War II, psychiatrists included the condition, under the name "gross stress reaction," in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The DSM gave clinicians a common language for mental health disorders and began to shape the ways the public viewed mental illness.

"Under conditions of great or unusual stress, a normal personality may utilize established patterns of reaction to deal with overwhelming fear," the entry states. "When promptly and adequately treated, the condition may clear rapidly."

The diagnosis was restricted to combat soldiers and those who experienced a "civilian catastrophe" (defined as fire, earthquake, explosion, etc.).

U.S. soldiers shell German soldiers retreating in northern France, July 11, 1944. (U.S. National Archives)

1968: Diagnosis removed from manual

The American Psychiatric Association removes "gross stress reaction" from the DSM. As a result, mental health professionals could no longer diagnose a soldier with a specifically combat-related mental illness. For Vietnam War veterans, the lack of a suitable diagnosis made it difficult to access health and disability benefits.

The American Psychiatric Association removes "gross stress reaction" from the DSM. As a result, mental health professionals could no longer diagnose a soldier with a specifically combat-related mental illness. For Vietnam War veterans, the lack of a suitable diagnosis made it difficult to access health and disability benefits.

A Marine recruiting poster from 1971 emphasized military toughness. (U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

"Post-Vietnam Syndrome"

U.S. troops carry a wounded soldier through a swampy area in Vietnam in 1969. (U.S. National Archives)

The military continues to use the term "combat fatigue" to describe emotionally distraught soldiers. Officials classified many soldiers as suffering from "character disorders," and focused on behavioral problems, rather than diagnosing mental illness.

After the war ended, the media began to refer to "Post-Vietnam Syndrome," to describe the psychological difficulties of returning soldiers, a term challenged by many military psychiatrists. A physician and supporter of the term described the symptoms in a 1972 New York Times article. The victims, he wrote, experienced "growing apathy, cynicism, alienation, depression, mistrust and expectation of betrayal, as well as an inability to concentrate, insomnia, nightmares, restlessness, uprootedness, and impatience with almost any job or course of study."

About 15 percent of American soldiers who served in Vietnam were still suffering from war-related mental health issues fifteen years after the war, according to a government-funded report published in 1990.

1980: Post-traumatic stress disorder gains acceptance

A Marine waits to take psychological tests at a base in California. The military is testing Marines and soldiers before they ship out, in search of clues that might help predict who is most susceptible to PTSD. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The American Psychiatric Association includes post-traumatic stress disorder in the updated DSM, after a prolonged fight by Vietnam War veterans and other groups. The diagnosis applied to people who suffered a psychologically distressing effect "outside the range of usual human experience." The DSM listed military combat as one potential source of trauma, along with rape, severe physical assault, and other types of trauma.

Symptoms are wide-ranging, and include flashbacks, dissociative episodes, efforts to avoid feelings or activities associated with the trauma, amnesia, a feeling of detachment or estrangement from others, insomnia, anger outbursts, and an exaggerated startle response.

In The Spotlight

-

The Current Music Blog

Your daily note for good music, news and pop culture. With attempted jokes.