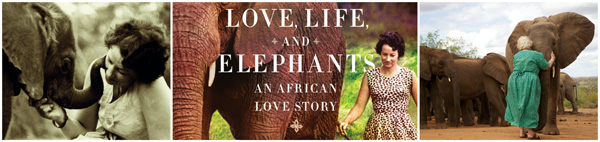

The First Baby Elephant Orphanage in Africa

Heather McElhatton

Part of A Beautiful World

Why do elephants line up to hug a little old lady in Nairobi National Park? She's their mother. Their adopted human mother. Dame Daphne Sheldrick has been saving orphaned baby elephants in Africa for over fifty years now, rescuing hundreds from certain death after their mothers and entire families were slaughtered by poachers for their ivory tusks. She founded the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya, where hundreds of orphaned baby elephants have been saved and returned to the wild.

Orphaned baby elephants is an ongoing and rising problem in Africa, as the ivory trade continues to decimate elephant populations. Poachers hunt mature elephants for their tusks, leaving newborns and adolescent elephants alone and abandoned. These orphaned elephants, many newborns, stand no chance of surviving on their own, it's critical they have their families to survive. Elephants mature at roughly the same rate that humans do, their lives can span 80 years. Just like human babies, baby elephants completely depend on their families for survival, for the first ten years of their lives. Their mothers provide them with milk for the first two years after they're born, and the extended herd provides physical protection from predators. Without their families, orphaned elephants die.

"For elephants, family is everything." Daphne says. "Their relationship with their families goes on long after death. You'll see elephants returning to the spot where a loved one has died, to visit their bones. And sometimes they'll carry off a bone with them."

We get many requests from people, and if we interview them and deem them compassionate and they understand why we exist, and what we need to do and they understand the role, that person will then spend time with us in the Bush with the other keepers and with the elephants, and it's all about whether the elephants accept that individual. There are some people they will just not take to. And they're reading the heart of that person, and sensing something in that person they can't relate to, and there's no empathy. Then there will be other people they take to immediately. Elephants can sense the goodness...or not..in an individual around them and you can see that every time people come and visit our elephants - we're open an hour every day - you see these different interactions, and you can see where the elephants are obviously reading goodness in people and are automatically drawn to them. We have one keeper for example, a gentleman named Mishak Nzimbi, who's been with us for twenty years now, longest standing keeper, and we call him "Mishak Magic," because he has something about him that every infant elephant, even those in the worst possible condition and health, they take to him and he can bring them back from the brink just by being who he is and its incredible to watch.

By way of airplane and bouncing jeeps, rushing through vast forests and savanna's to save themShe was the first person to figure out the right milk mix for the young orphans, allowing her to successfully save hundreds of orphaned elephants.

It has just about everything you would want in an orphanage: dormitories -- each orphan has a private room. There is a communal bath, a playground, and a dining area. There are as many as 14 orphans here at any one time and they stay a number of years before going back to the bush. The regimen at the orphanage is anything but Dickensian. Unlike Oliver Twist, when one of these orphans asks for more, that's what he gets. More.

"It's sad to say," Robert Brandford says. He's the Executive Director of The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. "But today in the wild, you'll see elephants turn their heads and hide their tusks from people, because they know they're being slaughtered for something on their face."

Daphne knows elephants in a way few humans do. She was born in Kenya during the summer of 1934. She grew up on her family's farm, exploring the wonders of East Africa's Great Rift Valley with her siblings, and her earliest memories were surrounded by animals and for her, it was completely normal to take a walk through the forest accompanied by a pack of family pets, which included a mob of dogs, Bob the impala, Daisy the Waterbuck and Rickey-Tickey-Tavey, a dwarf mongoose who ran ahead and led the pack down the scrub-lined trails.

Later in life, from 1955-1976, Daphne worked alongside her husband, David Sheldrick, the first and founding warden of Tsavo National Park in Kenya. Tsavo covers over eight-thousand square miles, and was wild, rugged terrain back then, thick with bush, tangled with vegetation and heavily populated with large herds of wild animals. As the founding warden, David was tasked with creating the first roads inside the park and building an infrastructure that would allow humans to visit and experience the vast, untamed African wilderness for themselves.

During that time, they lived inside the park and interacting with wild animals became a routine part of their daily lives. Whenever someone found a wounded or infant animal requiring assistance, they alerted the Sheldricks, who frequently took them in, and lived side-by-side with them.

"There are photographs of Daphne having tea on the lawn with baby elephants," Brandford says. "And elephants in the kitchen and sleeping in bed with her daughter. It's marvelous."

Daphne says her passion for Nature and philosophies about wildlife were heavily influenced by this time working with David, and guided her future endeavors to continue his work after he died.

"David's philosophy played a very important part in my understanding and interpretation of animal behavior. He believed that wild animals were, in many ways, more sophisticated than us humans, more perfect in terms of nature, honed by natural selection over millennial and specially adapted for the environmental slot they occupied, contributing to the well-being of the whole. He was intolerant of those who viewed animal intelligence as inferior to that of the human animal, for in his view, each species had evolved along a different branch of life in a way that suited its purpose; there were bound to be things that we humans would never fully understand about animal intelligence, and those who claimed they did merely illustrated ignorance. 'The more you know, the more you know you don't know,' he said. We should never be so arrogant as to believe we have all the answers."

- "Love, Life and Elephants, an African Love Story." by Dame Daphne Sheldrick

Survival is becoming more and more difficult for elephants. The ivory trade has decimated their numbers, and poachers hunt them tirelessly to fill the seemingly endless demand coming primarily from China.

Brandford says, "An elephant is killed every 15 minutes. At this rate, there won't be any wild elephants left in twenty years. Their species will die out in our lifetime. And for what? Ivory isn't used for medicine or food, it's used to ornament rooms. It's a decoration. To think we will lose an entire species for decoration is heartbreaking."

"Elephants are a keystone species," Brandford says. "If we lose elephants, we lose other species as as well.

LINKS: David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

Discover more stories from A Beautiful World on Soundcloud

Learn more about A Beautiful World