· CHAPTER ONE OF FOUR ·

After clergy sex abuse rocks a Louisiana diocese, a newly appointed bishop develops the tactics he'll later use in Minnesota.

Lafayette, La. — The Diocese of Lafayette stretches from the city south to Vermilion Bay, whose waters lead to the Gulf of Mexico. Down among the bayous and sugar cane fields of southern Louisiana, Catholicism runs deep.

Lafayette is the capital of Louisiana's Cajun country, about 135 miles west of New Orleans. Molly Bloom/MPR News

Lafayette is the capital of Louisiana's Cajun country, about 135 miles west of New Orleans. Molly Bloom/MPR News

Many of the 300,000 Catholics who live here trace their history back to the late 1700s, when their French ancestors fled Canada to escape British rule. In this humid, undeveloped land, they discovered waters filled with shrimp, oysters and crawfish, and they built churches on patches of dry ground.

For generations, they believed the priest served as the living face of Jesus Christ. He forgave their sins, baptized the young and anointed the sick. In his purity, he gave the faithful a glimpse of what heaven would be like.

No one had ever heard of a priest raping a child.

So when the Rev. Gilbert Gauthe arrived in the 1970s and showed an interest in young boys, no one paid much attention.

The priest took boys on camping trips and invited them for sleepovers in the rectory. He claimed to hold practices for altar boys every day at 6 a.m. and encouraged parents to let their boys spend the night.

His sexual appetite was uncontrollable. He put bars on the windows of a rectory. He kept a gun by the side of his bed, and when children refused to submit he threatened to use it. At night, he raped the boys, forced them to perform sex acts on each other, and took photographs on his Polaroid camera.

It went on this way for more than a decade. Gauthe remained in ministry even when his bishop learned that he had abused one boy and licked the faces of two others. After the second complaint, the bishop transferred Gauthe to a small church in the isolated town of Henry, La. On Sundays, the priest stood at the altar and surveyed his victims.

The vestibule of St. Mary Magdalene Church in downtown Abbeville, La. The Rev. Gilbert Gauthe served here from 1976 until 1977, when he was transferred to St. John in Henry. William Widmer/For MPR News

The vestibule of St. Mary Magdalene Church in downtown Abbeville, La. The Rev. Gilbert Gauthe served here from 1976 until 1977, when he was transferred to St. John in Henry. William Widmer/For MPR News

Finally, in 1983, a boy told his father, Wayne Sagrera, and Sagrera reported it to the diocese. The bishop sent Gauthe away for psychological treatment and offered nine families confidential settlements of more than $4 million.

One family refused to settle and went public, and the community awoke to the horror of what the priest had been doing to its children.

The Rev. Gilbert Gauthe (right) was transferred in 1977 to the parish of St. John (left), where he served the southern Louisiana towns of Henry and Erath. William Widmer/For MPR News and AP file photo

The Rev. Gilbert Gauthe (right) was transferred in 1977 to the parish of St. John (left), where he served the southern Louisiana towns of Henry and Erath. William Widmer/For MPR News and AP file photo

The Gastal family sued the diocese for failing to protect their 10-year-old son, Scott, who had been abused by Gauthe for more than a year. When Scott was hospitalized for rectal bleeding caused by the abuse, Gauthe stopped by to give him a toy car. The boy later worried that Gauthe would break into his parents' home and attack him. He would stay up all night checking the locks.

The boy testified graphically in court in 1986, struggling at times to find the words to describe what had happened. He said Gauthe had put his "pee-pee" inside him. The jury awarded $1 million.

The case made headlines around the country, especially after freelance reporter Jason Berry dug into the details and found a cover-up. As months passed, it became clear that Gauthe had been abusing children for decades. He later told a psychologist that he had abused more than 300 children. The scandal grew even after Gauthe pleaded guilty to 34 criminal counts and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

More parents threatened to come forward. Other priests were accused. Reporters began to wonder whether this was truly an isolated incident or an example of something that ran deeper and farther than a single diocese.

Their suspicions would prove correct. And the events unfolding in Louisiana would prove key to understanding a story that would play out decades later in Minnesota.

Vatican 'feared a domino effect'

The news from Louisiana soon reached the Vatican Embassy in Washington, D.C., where the Rev. Thomas Doyle, a young canon lawyer and fast-rising star in the church hierarchy, became alarmed. He wondered: How many other priests had abused children? And how many bishops had covered it up?

Doyle quickly concluded that the scandal of priests sexually abusing children – and the failure of the church hierarchy to stop it – could destroy the Catholic Church in the United States. The Vatican "feared a domino effect," he recalled in a recent interview. "The risk was the loss of prestige, the loss of power, the loss of respect," and the loss of money.

There was also the spiritual risk of scandal, a word that has a different meaning in the Catholic Church. Scandal threatens to separate believers from God. It could send people to hell.

The Rev. Thomas Doyle spoke to the 2002 national conference of Voice of the Faithful, a group that formed in response to the clergy sex abuse scandal. AP file 2002

The Rev. Thomas Doyle spoke to the 2002 national conference of Voice of the Faithful, a group that formed in response to the clergy sex abuse scandal. AP file 2002

As the crisis unfolded in 1985, Doyle teamed up with Ray Mouton, Gauthe's criminal defense attorney, and the Rev. Michael Peterson, who ran a treatment center in Maryland for priests with sexual disorders. They wrote a confidential report called "The Problem of Sexual Molestation by Roman Catholic Clergy." It warned that hundreds of priests might be abusing children and that lawsuits and settlements could cost the U.S. Catholic Church $1 billion in 10 years.

No one listened.

"They literally laughed that off," Doyle said. "You know, they were the Catholic Church, much too big and powerful to ever fall prey to these lawyers and these people."

He watched as Lafayette Bishop Gerard Frey, then 71, failed to repair the scandal. "There was no playbook at that time. Nobody knew how to do it," Doyle said.

Frey had offered prayers, policies and promises, but he couldn't undo his failure years earlier to act on the complaints about Gauthe. A local newspaper called for his resignation. In an interview, Frey said Gauthe had tricked him into thinking he was cured.

Frey wouldn't directly admit that he had been wrong to keep Gauthe in ministry. "Unfortunately, circumstances have proven that my subjective evaluation was in error," he said.

Doyle read the news reports with dismay. He suggested that the pope send a new bishop to Lafayette to serve alongside Frey for the next three years and then replace him when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 75.

He recommended a parish priest named Harry Flynn.

As bishop of Lafayette, Flynn hosted Mother Teresa at the Cajundome. Acadiana Catholic/1985

As bishop of Lafayette, Flynn hosted Mother Teresa at the Cajundome. Acadiana Catholic/1985

A contented pastor gets a call

Flynn "was very well respected at the time as a man, a priest who dealt well with other priests," Doyle recalled. "He had a reputation for being a really good guy, very pastoral, very compassionate, and that's why we focused on him rather than a company man who would be purely administrative."

Flynn was also a practical choice. "We thought that the church's reputation was going to be decimated anyway when the cover-up became known, and that the only way they would be able to redeem this was by truly sincere compassion and pastoral contact with the victims," he said.

Doyle would soon be disappointed.

Flynn, then 52, turned down the job at first and went to relax at his cabin in upstate New York. One night, a state trooper knocked on the back door.

"Are you Father Flynn?" the trooper asked. "Cardinal O'Connor wants you to call him tonight."

Flynn returned the call, and New York's Cardinal John O'Connor persuaded him to accept the job. The appointment took him by surprise, Flynn later said in an interview.

Flynn had been serving as pastor of St. Ambrose Catholic Church in Latham, N.Y., just a few miles from where he grew up. His connection to the priesthood began when he was 6 years old and watched a priest deliver a daily Eucharist to his dying father.

Flynn's mother died when he was 12, and the young orphan turned to the church for solace. He would stop by on his walk to school for a few moments of silent prayer. The Catholic Church seemed safe and enduring; its rituals offered comfort. Flynn later felt called to become a priest, and was ordained in 1960.

In the years that followed, he served as rector of the oldest seminary in the country, Mount St. Mary's in Emmitsburg, Md., and as a pastor in the Diocese of Albany. He felt his strongest connection to seminary students and other priests, and became known nationally as a leader in recruiting men to the priesthood.

Life as a bishop would be different. He would be responsible for all the souls in his diocese, parishioners and priests alike. He would become part of the fiercely competitive church hierarchy, in which promotions are influenced by loyalty and personal connections. If he impressed the Vatican and his fellow bishops, he might be promoted to cardinal, placing him in the small, influential group that elects the pope.

It was a lot for a parish priest to consider. But before any of that could happen, he needed to resolve the crisis in Lafayette.

The birth of a legend

Flynn would later claim that he healed the Diocese of Lafayette and restored the faith of its Catholics. Bishops, reporters and parishioners were amazed by his success, and Flynn, then the archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis, became a much sought-after expert on clergy sexual abuse.

"These people were crying out for someone to heal them fully," Flynn wrote in April 2002. "When they told me of the terrible acts perpetrated against them or their children, I was sometimes overwhelmed by the gravity and intensity of their accounts."

The Lafayette scandal showed him that "the bishop needs to quiet his own heart and be able to receive the confusion and hurt before attempting to respond to it," he told bishops in a 1994 national report on clergy sexual abuse.

"For a while, it was not easy being a Catholic in Lafayette." Archbishop Harry FlynnSiena College "Trusting the Clergy?" seminar, March 2003

At a national conference on the topic in 2003, Flynn addressed the audience as keynote speaker. "My experience of this problem as a bishop goes back to the place and almost to the time of the first case of this kind to gain widespread public attention," he said. "This was in the Diocese of Lafayette, La."

The assignment had been a painful one. "For a while, it was not easy being a Catholic – and definitely not a priest or a bishop – in Lafayette," he said. "One of the things that gives me hope in the current crisis is the experience I had in Lafayette of how people of good faith dealt with these terrible happenings. They were able, in a period of great testing, ultimately to discern between the grievous failings of the church's ministers and the truth and integrity of her Gospel message.

"This is not mere wishful thinking. The local church of Lafayette came to this realization only after suffering a great deal in facing up to the terrible things done to innocent children by men who should be among the most trustworthy in the community."

"[Flynn] was spit on, thrown in the mud." Rev. Jim Wiesner

During the dark days of the national scandal in 2002, Flynn's legend grew. "The story is that when they sent Archbishop Flynn to Louisiana, he had a driver take him to every family where there had been a victim," the Rev. Jim Wiesner, who served as a priest in Minneapolis in the 1990s, told the Memphis Commercial Appeal. "He was spit on, thrown in the mud. When people asked him, 'Why did you keep doing that?' he said, 'To give them an opportunity to voice their anger.'"

News organizations, including the Star Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press, repeated similar claims without verifying them. When U.S. bishops selected Flynn to lead their response to the national clergy abuse scandal, a Star Tribune editorial praised the selection as a sign that the church was serious about reform.

Flynn became the face of the church's response. He led the committee that wrote the church's policy, called the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People. His background gave the Catholic Church tremendous credibility at a moment of crisis.

There was just one problem. The story wasn't true.

Behind the scenes, a nightmare

Flynn arrived in Lafayette on a rainy day in July 1986 and moved into a residence with the vicar general, Alexandre Larroque, who had played a key role in covering up Gauthe's abuse.

Monsignor Alexandre Larroque Acadiana Catholic/April 1988

Monsignor Alexandre Larroque Acadiana Catholic/April 1988

The diocese newspaper announced Flynn's appointment with a banner headline, "The diocese gets a winner!" At a news conference, Flynn projected confidence: "If you know church history, the church has faced many crises through the years, but the church, which is Jesus Christ and the presence of the Lord, is bigger than any crisis, and the church will survive."

Behind the scenes lay a nightmarish situation. No one knew when the scandal would end or how to fix it. It seemed a new lawsuit was being filed every day.

Doyle, the Vatican Embassy official, told the new bishop to call Gauthe's attorney, Ray Mouton, for a briefing on the scandal. "He knows the ins and the outs, he knows the deep layers and he can help you more than anyone else," Doyle told him.

Mouton came from a prominent Lafayette family that had donated the land for the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist, the spiritual center of the diocese. He was sickened by his knowledge of Gauthe's crimes and wanted the church to offer counseling to every victim.

He never got a chance to suggest it. Flynn never called.

"My office was four blocks from his office," Mouton recalled in a recent interview, "so I wrote him a letter, a very nice letter. I welcomed him to Lafayette and stressed that it was urgent that I meet with him."

Years after representing Gauthe, attorney Ray Mouton wrote "In God's House," a fictionalized account of his experience. Courtesy M. Barrios

Years after representing Gauthe, attorney Ray Mouton wrote "In God's House," a fictionalized account of his experience. Courtesy M. Barrios

No reply.

Mouton and Doyle were disappointed, but there was little Doyle could do. Later that year, Doyle was forced out of his job – his career ruined, he said, because of his efforts to force the church to confront the abuse crisis. He would spend the rest of his life on the outside, helping victims and pleading with the church to protect children. Mouton also spent years pressuring the church to change, but the stress and conflict thwarted his quest.

Another Catholic attorney who had represented victims, Anthony Fontana, was frustrated in his efforts to get the bishop's attention. "There's another problem you need to know about," he told Flynn. A Lafayette priest named Gilbert Dutel had been accused of coercing young adult men into having sex.

Flynn offered a calm reply. He explained that Dutel was cured and that, regardless, he needed to keep him in ministry because of the priest shortage.

Fontana was dismayed. Flynn was just like the previous bishop, he thought.

Fontana would include the details of the conversation in a sworn affidavit later, in 1995. That affidavit – like thousands of other documents about the clergy sexual abuse scandal in Lafayette – was sealed by a federal judge as part of a massive insurance lawsuit the diocese filed two years after Flynn arrived. In the lawsuit, the church sought to force the insurance agency to reimburse it for settlements it had paid to victims.

Since then, the documents have sat in five dusty boxes in a federal office building in Fort Worth, Texas. There are no records of any major news reports on the suit, even though a judge lifted the seal in 1998.

Catholics celebrated Palm Sunday Mass in April at Lafayette's Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist. William Widmer/For MPR News

Catholics celebrated Palm Sunday Mass in April at Lafayette's Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist. William Widmer/For MPR News

Playing hardball in court

The files do not support the claim that Flynn healed the diocese. They also contain no suggestion that Flynn called police about priests accused of sexually assaulting children. Hundreds of documents reveal that Flynn's diocese used many of the same aggressive legal tactics that he would later employ in the Twin Cities.

Attorneys hired by the diocese argued that victims waited too long to come forward and that the public didn't need to know the names of accused priests. The diocese fought efforts by victims to seek compensation from the church and focused on keeping the scandal as private as possible, which meant that fewer victims came forward to sue.

In the case of Dutel, the documents show, the allegations weren't limited to young adults. Dutel had also been accused of sexually abusing a child. In an interview with a lawyer in 1992, the alleged victim said Dutel had abused him in the 1970s, starting when he was 9 years old.

Still, Flynn kept Dutel in ministry. No records exist of any reports to police.

Dutel, 69, now serves as the pastor of St. Edmond Catholic Church in Lafayette. Over the 22 years since his accuser came forward, Dutel has worked in elementary and high schools and served in several parishes. There's even a playground named after him.

• Source notes

• Explore the full investigation

Reached last week, Dutel denied the allegations and declined to say whether Flynn had informed him of the complaints: "I have a sense that I am not sure that I should be talking to you, because I don't know where this information is coming from." He declined an offer from MPR News to send him the documents for his review.

The diocese would eventually win its lawsuit against the insurance broker, Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. It would recoup more than $4 million despite the agency's plea that the courts make the church pay for the cover-up. "This Diocese does not deserve to be rewarded for its deceit, and the harm caused by that deceit and the criminal acts of its priests," the firm argued.

"Unbeknownst to Gallagher, the Diocese was a ticking time bomb," it said in another court filing. "Gallagher did not, and could not, foresee that the Diocese of Lafayette would have not one but several child molesters in its employ as Roman Catholic priests. Only the Diocese knew that it had active priests who had molested children. During the 1970's and early 1980's, the men who ran the Diocese of Lafayette manufactured a time-bomb of epic proportions.

"The time-bomb exploded in 1983 and since that time the Diocese has been hit by over a hundred claims relating to allegations that minors had been fondled, raped, sodomized and otherwise molested before, during or even after the Diocese began using Gallagher as its insurance agency in 1981."

In 1995, the agency called the rampant abuse by Gauthe and others "the equivalent of dozens of hurricanes." The diocese was "ground zero when it comes to pedophilia," it said, and "incredibly," most of the men who orchestrated the cover-up "are still in positions of leadership."

In August 1987, Flynn blessed the shrimp fleet in Delcambre. Acadiana Catholic/September 1987

In August 1987, Flynn blessed the shrimp fleet in Delcambre. Acadiana Catholic/September 1987

Shrimp boats and candy

While the insurance lawsuit made its way privately through the courts, Flynn kept busy. He recruited men to the priesthood, welcomed Mother Teresa to a packed event at the Cajundome and celebrated a special Mass for lawyers. He spent Christmas Eve with inmates at a Lafayette jail. On Valentine's Day, he delivered candy to each of the diocese's nearly 100 employees.

"Bishop Flynn does indeed seem to be everywhere, having come into the Lafayette Diocese like an Irish whirlwind, sweeping the people of Acadiana right off their feet with his Gaelic charm," a columnist for the diocese newspaper wrote in May 1989. (Acadiana is an informal name for French Louisiana.) "His calendar is booked months in advance, yet those really in need seem always to have access to him."

The rural town of Delcambre, La., is roughly 20 miles south of Lafayette. Molly Bloom/MPR News

The rural town of Delcambre, La., is roughly 20 miles south of Lafayette. Molly Bloom/MPR News

The New York priest embraced Cajun life. He played a starring role in the biggest event of the year – the blessing of the shrimp fleet in the waters off Delcambre, on the southern edge of the diocese.

The local Catholic newspaper celebrated the event with a full-page cover photo in September 1987. The photo shows Flynn, in a white robe and red cap, standing on the deck of one of the shrimp boats.

As thousands looked on from shore, boats lined up in the water. They circled around, one by one, and Flynn threw holy water on them.

Down along the water in Delcambre, Mike LeBlanc, who runs a gas station where shrimp boats fuel up, still remembers Flynn's visit, although he was just a child at the time. It was unusual for a bishop to come down to bless the fleet, he said. "I don't know why he came that year, but it was something nice, real nice. It was a big thing here."

The Rev. Chester Arceneaux stood on the boat with Flynn that day. Arceneaux was a new priest at the time. Now he's the pastor of the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist, the most prominent church in the diocese.

Last April, on Palm Sunday, Arceneaux, dressed in a long red robe, led a procession of children carrying palm fronds into the cathedral. The church was packed, and the priest reminded the Cajun crowd of the need to fast for Lent. "That includes crawfish," he said.

The Rev. Chester Arceneaux (left) is now pastor of the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist parish in Lafayette. He was ordained by Bishop Harry Flynn and remembers him fondly. William Widmer/For MPR News

The Rev. Chester Arceneaux (left) is now pastor of the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist parish in Lafayette. He was ordained by Bishop Harry Flynn and remembers him fondly. William Widmer/For MPR News

After shaking the hands of departing parishioners, Arceneaux stayed outside for a few minutes to talk about his memories of Flynn, the bishop who ordained him.

Flynn was a father figure to him, he said, a spiritual leader who connected with priests and parishioners alike.

"He was a great listener and a great healer of the people who were struggling at the time of the scandals that we had here within the diocese," he said. "He had that beautiful gift of knowing people personally and knowing their experience. And that's what gave the church of Lafayette, at a difficult time it was, that great hope...that truly the shepherd had come to nurture them and to listen to them and to heal them."

The Diocese of Lafayette's headquarters sits just beyond the city's center. William Widmer/For MPR News

The Diocese of Lafayette's headquarters sits just beyond the city's center. William Widmer/For MPR News

The nun who lived Flynn's legend

Others closer to the scandal had a different opinion.

While Flynn was immersing himself in Cajun life, a nun and former teacher named Sister Bartholomew DeRouen was trying to reach out to parents whose children had been abused by Gauthe.

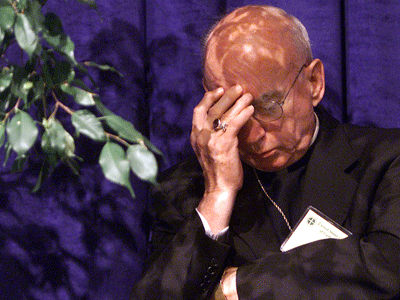

Bishop Gerard Frey Courtesy McNeese State University archives

Bishop Gerard Frey Courtesy McNeese State University archives

Sister Bartholomew, who goes by "Sister B," was given the job by Bishop Frey in 1985 after the Gauthe scandal broke. Frey felt uncomfortable meeting with the families, he would later testify, and thought a woman could do a better job.

But Frey didn't make the job any easier. He wouldn't give Sister Bartholomew the names of victims, so she spent hours driving aimlessly up and down rural roads. Out of desperation, she visited Gauthe in prison. He refused to help.

"It was like talking to evil," she recalled. "He said, 'I didn't molest any of those boys. I just made them feel good.'"

She found some families by chance, as happened one day when she stopped at a random house to ask a favor. The woman at the door cut her off. "We know who you are," she said. "And we don't have any use for you here."

"Actually," Sister Bartholomew said, "I'm just wondering if I could use the bathroom."

Five minutes later, the whole family had gathered in the living room. They were ready to talk.

"I blessed my bladder that day," she said.

However, there was little she could do in most cases. Parents did not want to return to the parishes where their children had been abused. When Sister Bartholomew suggested other pastors, parents would shake their heads and tell her that those priests, too, were suspected of sexually abusing children.

And then, when Flynn arrived, Sister Bartholomew almost lost her job. One of Flynn's closest advisers, Monsignor Richard Greene, tried to fire her, she said, but she refused to leave.

Greene and other priests saw the Gauthe scandal as a way to advance their careers, she explained. "It was like once it came out in the open and people began to talk about it, it became sort of the 'in' thing to be involved with the Gauthe situation, to be one of the good guys," she said.

Although Flynn was more charming than Frey, she said, he also gave her no names. Nor did he go door to door to talk to victims, as would later be asserted, she said. "He was a disappointment."

Neither Flynn nor Frey seemed to understand how deeply the families had been harmed by the abuse and the church's cover-up, she said. "I think they just put their heads in the sand."

Greene, reached in April, said he barely knew Flynn. "I was simply a pastor in one of the parishes," he said.

Monsignor Larroque, who lived with Flynn and served as one of his top deputies, was similarly reticent. When asked to share his memories of working alongside Flynn, he paused. "I'd rather not," he said.

Lennis Baudoin is among the fishermen who collect crawfish from traps next to St. John church in Henry. William Widmer/For MPR News

Lennis Baudoin is among the fishermen who collect crawfish from traps next to St. John church in Henry. William Widmer/For MPR News

'The church came first'

A short drive from the shrimp boats in Delcambre are the isolated communities of Henry and Esther, where alligators outnumber people and sugar cane fields stretch on for miles. It's where Gauthe terrorized hundreds of children.

Wayne and Rose Sagrera built their home here in 1974. They run a successful alligator farm, with hundreds of reptiles kept in locked pools across the field.

At the front door, two alligator-shaped gargoyles welcome visitors. Inside the airy home, pictures of children and grandchildren line the walls.

The small towns of Esther and Henry lie 25 and 10 miles from Delcambre, respectively. Molly Bloom/MPR News

The small towns of Esther and Henry lie 25 and 10 miles from Delcambre, respectively. Molly Bloom/MPR News

Three of the Sagreras' sons were abused by Gauthe. In 1983, Wayne Sagrera became the first to report the abuse to the diocese, and he pleaded with a church official to remove Gauthe from ministry. The official told him, "Well, you know, we don't have anybody to say Mass Sunday," he recalled.

Sagrera told him, "It really doesn't make too damn much difference because the anger is starting to swell in the community, and someone can possibly kill him and if I see him it will probably be me."

The threat worked. Church officials sent Gauthe away for psychological treatment. The Sagreras later accepted a private settlement from the diocese for several hundred thousand dollars.

Family members were still in shock when Flynn arrived in 1986, three years after they had first learned of the abuse. The Sagreras had formed a weekly prayer group with the families of about six other victims.

Flynn began attending the prayer group. "He said that he came here to heal," Wayne Sagrera said.

But the new bishop struggled to relate to the families, Rose Sagrera recalled. He listened but showed no emotion. The meetings seemed awkward and forced.

"I don't think that he got, or could get in touch with, the human suffering that was going on," she said. "I don't think he had a hold on that at all. I don't know if he didn't care or wasn't capable. I don't think he got that. If you get that human suffering, you have to show some feelings, you have to care, and we didn't see that."

The Sagreras tried to socialize with Flynn to make him feel welcome. They brought one of their sons to a barbeque with the new bishop and his adviser, Monsignor Greene, the same priest who had tried to fire Sister Bartholomew.

Flynn didn't talk to the boy. And at one point, Greene pointed at the boy and said, "See that child right there? He's the reason Harry Flynn is a bishop."

Wayne Sagrera hadn't given up on Flynn, though, and wondered if it would be better to meet with him alone. In several private meetings, he pleaded with Flynn to reach out to the parishes where Gauthe had served to find other victims and offer them counseling.

He told the new bishop that Gauthe had acknowledged abusing hundreds of children, but that only a few dozen had come forward. He worried about the other kids, particularly because many of the parents were in denial about what had happened.

Flynn's response startled him. Flynn admitted that the church had been wrong to keep Gauthe in ministry and that it had mishandled the entire situation. But, he explained, there was nothing he could do.

"[Flynn] was here not to heal. He was here to save the Catholic Church in this area." Wayne Sagrera

"He used the excuse that he made a vow to protect the church," Wayne Sagrera recalled. "He made it very plain that the church came first...On numerous occasions he admitted they were at fault, but he would not come forward and do anything about it."

Wayne was furious. "I guess maybe I'm a little bit simple a human being, but to me your responsibility lies with your parishioners, not with the church," he said.

The final straw came when the Sagreras asked Flynn for a favor.

Their second-youngest son, who had been abused by Gauthe starting at age 6, was slowly recovering from the abuse. He'd spent six months in a psychiatric hospital after he told his parents that he wanted to kill himself. After he was released, he told his parents that he wanted to go back to being a regular kid.

He returned to his Catholic elementary school and asked to join the football team. His parents took it as a good sign that he was on the mend. But the school counselor refused to let him play.

The Sagreras asked Flynn to intercede. As bishop, he could override the decision. "He very coldly said no," Rose Sagrera said. "The child had to follow the school rules, and there were no exceptions."

"That finished it off," Wayne said. "That was the last meeting with Bishop Flynn."

The families' prayer group broke up. "It was causing more pain than healing," Rose recalled.

The couple said they're not surprised that people think Flynn healed the diocese.

Wayne said, "It's hard for someone who is not directly involved" to understand the pain felt by the victims and their families. "So I'm sure some of those people feel, 'Well it's taken care of now. The bishop came and everything's good.'...But I don't see how healing can be done if you don't deal with the people who were involved, if you don't come forward and do something for these children."

He finds Flynn's claim that he healed the diocese offensive. "He was here not to heal. He was here to save the Catholic Church in this area."

The Sagreras' boys are now doing well. But some of the other victims, they said, never really recovered.

Scott Gastal, 40, testified when he was 11 that he had been abused by the Rev. Gilbert Gauthe, his family's parish priest. William Widmer/For MPR News

Scott Gastal, 40, testified when he was 11 that he had been abused by the Rev. Gilbert Gauthe, his family's parish priest. William Widmer/For MPR News

'I wanted to put a stop to it'

The boy who sparked the national clergy sexual abuse scandal is now 40 years old.

Scott Gastal lives with his girlfriend in a small home in Mouton Cove, just a few miles down the road from the church where he was abused. Most days he doesn't leave the house.

During a recent visit, the front door stood open. Inside, the home was empty except for a mattress on the floor of the living room, a few prescription pill bottles, and a crucifix hanging above the front door.

Gastal is 6 feet tall and thin, with a receding hairline and dark circles under his eyes. He wore an orange T-shirt and dark blue athletic shorts. He appeared fragile and shy, apologizing for the lack of chairs and offering a seat on the bed.

He said he would be moving soon. He wanted to get away from this place where everyone knows what happened.

But he said he doesn't regret telling the world what Gauthe did.

"I wanted to put a stop to it," he said. "I wanted the man to pay for what he did to me...I feel at least I stopped something, a monster, from doing it to other kids."

The abuse "just had a major effect on my life," he said softly, pushing his hands into the mattress. "Things I wanted to accomplish in life I couldn't get done because of it."

Gastal said he suffers from severe post-traumatic stress disorder and insomnia brought on by the abuse, and receives federal disability payments as a result. He said he was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown in 1998. "Things just started all to build up on me," he said, "and before I knew it, it was just out of control."

Now he sees a therapist once a month and hopes to go to school to become a social worker.

He never received any of the $1 million awarded to him. His parents spent it before he was old enough to claim it.

"How I feel is that the church let me down," he said, "and lawyers soon after let me down because they didn't invest the money right. I wasn't taken care of the way I was supposed to."

Gastal said he never met with Flynn or anyone else from the church, and no one apologized to him or his family. He was surprised to learn that Flynn claims he met with all the victims and healed the diocese.

"That's the first I'm hearing of anything like that," he said.

Gastal sometimes runs into other victims of Gauthe, but they don't have any support group or other assistance. "Nobody sticks together like that."

He said he hopes his story encourages other victims of sexual abuse to get help.

Roach announced Flynn's appointment as his successor and coadjutor bishop of the Twin Cities archdiocese in February 1994. Courtesy KARE-11

Roach announced Flynn's appointment as his successor and coadjutor bishop of the Twin Cities archdiocese in February 1994. Courtesy KARE-11

St. Paul's next archbishop

None of the other Gauthe victims has come forward publicly to talk about what happened. The silence has allowed the horror to fade in the minds of most parishioners here.

By the time Flynn left Lafayette, he was beloved by many. He'd won praise from his fellow bishops and had been appointed to serve on a national committee on clergy sexual abuse. One of his fellow committee members was Archbishop John Roach of St. Paul and Minneapolis, where the Catholic Church's second major clergy abuse scandal had broken in 1987.

Roach admired the Lafayette bishop, 12 years his junior. When it came time for Roach to retire, he suggested Flynn as a successor. The Vatican agreed, and the appointment was announced in February 1994.

At a news conference, Roach praised Flynn's work: "Since coming to the Lafayette Diocese, he has reached out with compassion and reconciliation, encouraging harmony, always stressing the spiritual dimension of daily life."

Flynn said he welcomed the new assignment. "Lafayette has been very good to me and I hope that I will find that same love and that same nurturing in this archdiocese," he said.

In Lafayette, thousands packed the cathedral for one final Mass. At a reception, Flynn shook the hands of parishioners for nearly six hours.

Editor's note (July 23, 2014): This story has been updated to more precisely describe what led Ray Mouton to end his efforts to change church policy.

This story was reported by Madeleine Baran with help from Sasha Aslanian, Meg Martin, Tom Scheck and Laura Yuen. It was edited by Eric Ringham. The project's editor is Chris Worthington.

Top photo: St. Mary Magdalene Church in downtown Abbeville, La., where the Rev. Gilbert Gauthe served from 1976 until 1977. William Widmer/For MPR News

«

Documentary

«

Documentary  Chapter 2 »

Chapter 2 »