· CHAPTER FOUR OF FOUR ·

A new archbishop's top adviser wants no part of the decades-long effort to protect abusive priests and keep their crimes secret.

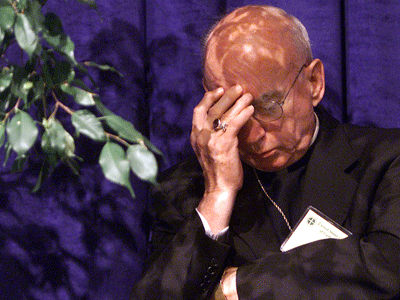

Bishop John Nienstedt was driving near Marshall, Minn., on April 2, 2007, when his phone rang with a call from the Vatican Embassy.

Cell phone reception was spotty, and it took nearly an hour to understand that Pope Benedict XVI had appointed him as the new archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis. He would take over in May 2008 when Archbishop Harry Flynn retired.

In the Twin Cities, reaction was mixed. Catholics had grown accustomed to the less doctrinaire approach of Flynn and his predecessor, Archbishop John Roach.

Twin Cities Archbishop Harry Flynn announced in 2007 that New Ulm Bishop John Nienstedt had been appointed his successor. The two shared a year of transition before Flynn's 2008 retirement. Greta Cunningham/MPR News file 2007

Twin Cities Archbishop Harry Flynn announced in 2007 that New Ulm Bishop John Nienstedt had been appointed his successor. The two shared a year of transition before Flynn's 2008 retirement. Greta Cunningham/MPR News file 2007

Nienstedt had built a reputation as the conservative bishop of New Ulm, Minn. He criticized parishioners who missed weekly Mass, spoke of Satan's efforts to drive men away from the priesthood and warned that "homosexual inclination is a result of some psychological trauma" that occurs before the age of 3.

He saw himself as fighting for the souls of the faithful. "Believing in sin has become countercultural," he wrote in 2005. "Oh, the reality of crime, violence, road rage, sexual promiscuity, infidelity and deceit are all around us."

The new archbishop exuded self-control. At age 61, 6 feet tall, trim, with perfect posture, Nienstedt kept his black clerical outfit spotless and his short gray hair neatly trimmed. When he walked into a room, he expected everyone to stand.

Nienstedt told a reporter that he would work to establish trust with priests, restructure the chancery and reduce the archdiocese's debt.

But the archbishop would soon encounter a situation more troubling than financial debt. He had walked into an archdiocese that was nearly three decades into a cover-up of clergy sexual abuse.

Nienstedt would later claim that he was "blindsided" in the fall of 2013 by an MPR News investigation that showed top church leaders had covered up abuse for decades.

"When I arrived here seven years ago, one of the first things I was told was that this whole question of clerical sexual abuse had been taken care of, I didn't have to worry about it," Nienstedt told reporters in December. "Unfortunately, I believed that."

However, hundreds of memos and dozens of interviews show that, within weeks of his arrival, Nienstedt learned that his predecessors had violated Vatican rules on clergy sexual abuse cases and hadn't reported abuse to police. He also learned that the archdiocese had ignored Vatican rules on church finances.

Nienstedt chose not to reveal the cover-up. Instead, he contributed to it.

'A plague to the church'

Though he didn't realize it at the time, Nienstedt set in motion the unraveling of the chancery's secrets as soon as he arrived.

The archbishop's first decision was to remove the Rev. Kevin McDonough from the top post he'd held for 17 years.

Vicars general

Three priests have served as vicar general and moderator of the curia — a position sometimes described as the archbishop's chief of staff — under Archbishop John Nienstedt after the Rev. Kevin McDonough, who had been appointed by Archbishop John Roach and also served under Archbishop Harry Flynn.• Rev. Kevin McDonough (1991-2008)

• Bishop Lee Piche (appointed June 2008)

• Rev. Peter Laird (2009-2013)

• Rev. Charles Lachowitzer (Nov. 2013-present)

The archdiocese often has more than one vicar general serving at a time — but only one who is also moderator of the curia.

As vicar general, McDonough had managed the archdiocese's response to clergy sexual abuse for Flynn and Roach. He negotiated secret deals with abusers, met with victims and worked to keep the scandal quiet. Nearly every allegation of clergy sexual abuse had crossed his desk.

Now McDonough was out of the inner circle. He had accepted a less prominent job as head of the archdiocese's child safety programs.

Nienstedt appointed the Rev. Lee Piche as his new vicar general. A year later, he appointed a second vicar general, the Rev. Peter Laird, who took over most duties.

The archbishop gave one of the most sensitive jobs in the chancery to a 33-year-old canon lawyer named Jennifer Haselberger. As chancellor for canonical affairs, Haselberger managed the archdiocese's files and advised the archbishop on church law. She had access to thousands of top-secret memos and handwritten notes kept locked in the chancery vault.

Haselberger was a devout Catholic who admired the complex, 2,000-year-old legal system of the Catholic Church. She received a license to practice canon law from a Catholic university in Belgium and returned to the U.S. in 2004, two years after the Boston abuse scandal broke. She had also worked for the dioceses of Crookston and Fargo.

Haselberger saw her work on abuse cases as a way of living out her faith. "This is really staring in the face of what I can only describe as evil — and just a plague to the church," she said.

"I'd always felt that part of my job was helping to restore justice." Jennifer HaselbergerJeffrey Thompson/MPR News file 2013

She believed that the church's canon law system had the power to help victims, punish abusers and restore the trust of parishioners.

Haselberger took comfort in being able to tell victims that "the Holy Father himself heard you, believed what you were saying, and has imposed the penalty of dismissal," she said. "You really had a sense that justice was being done."

The Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis chancery — which houses its administrative offices — overlooks the city of St. Paul, at the corner of Summit and Selby avenues.Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

The Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis chancery — which houses its administrative offices — overlooks the city of St. Paul, at the corner of Summit and Selby avenues.Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

Unfamiliar with the rules

In St. Paul, Haselberger found herself surrounded by attorneys and priests who did not share her enthusiasm for the laws of the church.

Right away, she encountered resistance.

Rev. Francisco "Fredy" Montero Monar was arrested in June 2007 on allegations that he had sexually abused a 4-year-old girl. | Background and assignment history Ambar Espinoza/MPR News file

Rev. Francisco "Fredy" Montero Monar was arrested in June 2007 on allegations that he had sexually abused a 4-year-old girl. | Background and assignment history Ambar Espinoza/MPR News file

That summer, a visiting priest from Ecuador, the Rev. Francisco Montero, had fled during a criminal investigation into whether he had sexually abused a 4-year-old girl. No one had reported the allegation to Rome, a step required by canon law.

When Haselberger asked a chancery official for an explanation, the official claimed not to know it had to be reported, she said.

She couldn't understand how an archdiocese that claimed to be a national leader on clergy sexual abuse didn't know the rules.

"I mean you could literally go to Google and say 'what to do when a priest had been accused of sexual abuse of a minor.' Anybody could find it," she said. "And so the idea that they were unaware and that that hadn't been done, just completely had me taken aback."

In her third month on the job, she learned that McDonough, Flynn's top deputy, had given a "verbal OK" for a priest accused of sexual misconduct to return to his religious order.

She notified Nienstedt in a memo: "I would prefer to have something in writing regarding the accusation, the investigation, and its resolution."

Nienstedt replied with a handwritten note: "I do not understand your reaction. It seems a bit extreme."

Haselberger stumbled across a far worse problem a few weeks later, when Nienstedt asked her to review the files of priests who had sexually abused children to make sure the paperwork was in order.

Haselberger thought it would be a quick check. She assumed Flynn would have asked the Vatican to defrock most abusers. If any remained, she expected that they would be elderly and living a closely monitored life of "prayer and penance," as required by church law.

Instead, the records she found showed that only 11 priests had been reported to the Vatican for alleged sexual abuse of children. The files indicated that Flynn had not asked the pope to defrock any of them. She couldn't find any official restrictions, either. Most of the priests lived in private homes.

"I was absolutely shocked," Haselberger said.

She notified Nienstedt.

The archbishop told Haselberger that he had too many problems to fix all at once.

A statue of Girolamo Savonarola stands in Ferrara, Italy. sterte/Creative Commons via Flickr

A statue of Girolamo Savonarola stands in Ferrara, Italy. sterte/Creative Commons via Flickr

"As you have probably noticed by now, there have been in the past a good number of transactions in which proper canonical processes were not followed or, if followed, they were not properly recorded," Nienstedt wrote in a Dec. 19, 2008, memo to Haselberger.

"Given this situation, I do not believe that it is prudent for us to try and correct all the mistakes of the past thirty years in my first six months."

He added, "I certainly do not want to become known as the Archdiocesan Savonarola."

Girolamo Savonarola was a Dominican friar who was excommunicated in 1497 after he denounced corruption in the Catholic Church.

'Blue memo Mondays'

Although the archbishop and Haselberger worked in offices close to each other, they rarely spoke. Nienstedt told his senior advisers that he preferred to communicate in writing.

At a meeting of senior advisers, Nienstedt said, "Don't talk to me," Haselberger recalled. "If you see me in the halls, don't stop me and ask a question about something you're working on because if you do, I will say whatever it takes to get you to end the conversation."

• Source notes

• Explore the full investigation

Chancery employees began to dread what they referred to as "blue memo Mondays," when they would come to work and find missives from Nienstedt on blue paper.

Nienstedt reprimanded the archdiocese's attorney for not wearing a tie to a meeting. He demanded that the accounting director explain why he left a light on in the chancery garage over the weekend. He complained about the size of the margins on a Word document.

At the top levels of the chancery, the reliance on memos fueled rumors and petty rivalries.

Senior advisers rarely debated important issues openly. Instead, they wrote memos directly to the archbishop that tried to anticipate and address objections that other advisers might raise in their own memos.

Decisions that could have been made in five minutes took months.

In one case, senior advisers debated in memos for more than a year whether images on a priest's computer met the legal definition of child pornography.

Haselberger ended that dispute in February of 2013, when she reported the images to the Ramsey County Attorney's Office.

Documents stashed in boxes

Haselberger spent most of her time trying to organize the archdiocese's files.

"When I started, the priest files were just an absolute mess," she recalled.

"So you'd have a Manila folder and you'd have everything kind of stuffed in there, from mimeographed papers from way back to copies of letters to memos, just all in this kind of mad jumble, no order whatsoever."

The chancery kept its clergy files in a locked vault on the first floor.

Attorney Jeff Anderson

Jennifer Simonson/MPR News file 2013

Attorney Jeff Anderson

Jennifer Simonson/MPR News file 2013

But Haselberger and her employees soon realized that the most incriminating documents on alleged sex crimes by priests had been removed.

Victims' attorney Jeff Anderson had suspected for decades that the archdiocese hid documents on abusers in a "secret archive." The Vatican, he knew, required each diocese to maintain such an archive for its most sensitive files.

Haselberger found the mysterious "secret archive" in the corner of the basement. It was a small metal safe — and it was empty. Instead, she discovered the documents stashed in boxes in the chancery basement and in a filing cabinet behind an empty desk that used to belong to McDonough's secretary.

Haselberger and her employees in the records department began to sort the priest files into color-coded binders.

As Haselberger organized the files, she found evidence of earlier cover-ups.

She learned that the Rev. Joseph Gallatin had touched the chest of a 17-year-old boy while he slept and had remained in ministry despite his sexual attraction to teenagers.

She found that the archdiocese was paying the Rev. Michael Stevens, a convicted child abuser, to help maintain a database related to clergy sexual abuse.

Rev. Joseph Gallatin: Background and assignment history The Catholic Bulletin

Rev. Joseph Gallatin: Background and assignment history The Catholic Bulletin

Rev. Michael Stevens: Background and assignment history The Catholic Bulletin

Rev. Michael Stevens: Background and assignment history The Catholic Bulletin

Stevens had pleaded guilty in 1987 to sexually abusing a 14-year-old boy in a Fridley motel room. His file showed that he had remained in the priesthood and was later hired by Flynn to work on the archdiocese's computers. When the Boston abuse scandal broke in 2002, Flynn announced that he would remove Stevens as an employee. Privately, the archbishop hired him back as an independent contractor. Some of Stevens' work involved parishes with schools.

Haselberger warned that the job could give Stevens access to children. "There is no lessened liability or responsibility because he is working on computers," she told Laird in a June 9, 2011, memo.

She added that a "psychosexual evaluation and risk assessment" of Stevens in 2005 had recommended "diligent monitoring" — but Stevens had met with a monitor just six times in two years.

No one acted on Haselberger's complaints. Stevens and Gallatin remained in their jobs until MPR News reported the cover-up last year.

Haselberger handled every problem with the same urgency and attention to detail. At times, her approach could be grating.

When she returned from a vacation in the fall of 2009, she was annoyed to learn that Nienstedt had appointed an Eastern rite priest to serve as pastor in violation of canon law.

"I have begun the process for requesting a bi-ritual indult, but it is unclear if his Archbishop in India will support it, and the parish remains in limbo until it is done," she wrote in a memo to Laird.

"It can't be; I warned them." Jennifer HaselbergerJeffrey Thompson/MPR News file 2013

A warning ignored

When priests came up for reassignment, Haselberger checked their files.

Sometimes she found disturbing information. In April 2009, Haselberger learned that the Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer had approached young men for sex at a Barnes and Noble store in Roseville several years earlier, cruised nearby parks and received treatment for sexual problems. She read angry letters that McDonough, the former top deputy, had received in 2004 from the father of one of the young men approached at the bookstore.

"As difficult as it is to say, I cannot help but get a sense that this is just going to 'quietly go away,'" the man wrote. "That I will never hear of anything more, until God forbid, I read a police log or hear of another individual being approached."

She alerted Nienstedt and urged him to review the file before he decided whether to appoint Wehmeyer as a pastor.

"I remember thinking at the time, all I have to do is tell him this, and the argument is done," she said.

While she waited for a response, more complaints came in. A priest called to say that Wehmeyer had approached him for sex. Someone else reported seeing Wehmeyer acting suspiciously with boys at a campground.

Later that year, Nienstedt appointed Wehmeyer as pastor of Blessed Sacrament and St. Thomas the Apostle, two St. Paul parishes that have since merged.

The former top deputy who handled the initial complaints about Wehmeyer recommended that the archdiocese not tell parish employees about his sexual misconduct.

"I think that you share with me the opinion that he really was not all that interested in an actual sexual encounter, but rather was obtaining some stimulation by 'playing with fire,'" McDonough wrote in a 2011 memo to the head of the archdiocese's monitoring program. "This sort of behavior would not show up in the workplace."

The Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer is serving a prison sentence for abusing two boys in 2010. | Background and assignment history Courtesy Minnesota Department of Corrections

The Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer is serving a prison sentence for abusing two boys in 2010. | Background and assignment history Courtesy Minnesota Department of Corrections

Wehmeyer abused the sons of a parish employee in the camper he parked outside the Blessed Sacrament rectory. Courtesy St. Paul Police Department

Wehmeyer abused the sons of a parish employee in the camper he parked outside the Blessed Sacrament rectory. Courtesy St. Paul Police Department

By that time, Wehmeyer had already abused two sons of a parish employee.

Wehmeyer had lured the boys into a white camper he kept outside the rectory, where he gave them alcohol, showed them pornography and told them to touch themselves. At least once, he touched one of the boys.

The boys reported the abuse to their mother in 2012, and Wehmeyer was arrested.

Haselberger was devastated by the thought that she had failed to protect children from an abusive priest.

"From the very moment, I've been asking myself, 'What else could I have done? What pressure did I not apply? Who didn't I talk to? What on earth could have happened?'" she said.

In the months after Wehmeyer's arrest, no one held meetings to talk about how the abuse had happened or how similar cases could be prevented, she said.

Instead, officials focused on how to spin the story as an example of the church's quick response to allegations of sexual abuse.

Haselberger began to doubt whether she should continue as chancellor.

For four years, she had brought her concerns to Nienstedt or her fellow deputies. She'd written memos and emails. None of it had protected those two boys.

Rev. Harry Walsh: Background and assignment history Jeffrey Thompson/MPR News

Rev. Harry Walsh: Background and assignment history Jeffrey Thompson/MPR News

'It will surface the question'

Haselberger was torn because, in a handful of cases, Nienstedt had followed her advice.

The archbishop tried to remove two men — the Rev. Harry Walsh and the Rev. Joseph Wajda — from the priesthood. Both had been accused of abuse decades earlier and denied the allegations.

Nienstedt explained to the Vatican why the archdiocese hadn't reported the allegations against Walsh sooner. "As you are aware, I only become Archbishop of Saint Paul and Minneapolis in May of 2008," he wrote. "Therefore, these decisions were taken prior to my arrival in this Archdiocese."

Although Nienstedt was successful in getting Walsh kicked out, he didn't tell parishioners. No one knew that Walsh had been accused of abuse or that he was no longer a priest.

St. Henry Catholic Church in Monticello Jeffrey Thompson/MPR News

St. Henry Catholic Church in Monticello Jeffrey Thompson/MPR News

Parishioners at St. Henry Church in Monticello, where Walsh served as music minister, accepted Walsh's explanation that he had decided to retire to focus on other projects. They threw him a party and collected donations.

Walsh also taught sex education to teenagers under contract in Wright County. He remained in that job because Nienstedt chose not to disclose the allegations. After MPR News approached Wright County with the information in December 2013, Walsh's contract was terminated.

The archdiocese couldn't release information about abusive priests without revealing that past archbishops had covered up their abuse.

Nienstedt encountered the same problem in the case of the Rev. Joseph Wajda in the summer of 2012. The archbishop learned that the Vatican had decided to defrock Wajda, who had been accused of alleged sexual abuse in the 1980s.

"We run the risk of being perceived incorrectly if we try to keep this below the radar." Sarah Mealey

It was the first time that the archdiocese had followed the Vatican process for defrocking a priest for abuse, Communications Director Sarah Mealey wrote in an email to senior advisers.

Mealey wanted to release a public statement.

"I do not recommend that we keep this as private communication — mainly because, in this day and age, frankly nothing is 'private' and we run the risk of being perceived incorrectly if we try to keep this below the radar," she wrote.

Haselberger forwarded the email to Eisenzimmer, the archdiocese's attorney.

"Thoughts?" she wrote.

Eisenzimmer replied, "It will surface the question of naming other abusers and why we didn't do this with others."

Financial secrets unravel

Some of the deepest secrets of the cover-up unraveled when the archdiocese brought in an outside auditing firm in 2012.

The auditors had been hired to investigate allegations that accounting director Scott Domeier had stolen money from the chancery. Domeier would later plead guilty to stealing nearly $700,000.

As they looked for suspicious transactions, the auditors found the secret payments to abusive priests that Flynn and McDonough had set up years earlier.

The auditors told Haselberger, and she notified Nienstedt.

"There is little doubt of the scandal that would result should the fact of these payments become public," Haselberger wrote in a four-page memo to Nienstedt on Feb. 17, 2012.

She described the payments to three admitted abusers — the Rev. Robert Kapoun, the Rev. Clarence Vavra and former priest Lee Krautkremer — as well as payments to the Rev. Stanley Kozlak, who fathered a child with a married parishioner, and to two other priests.

"I believe that there is some risk that these records could be subpoenaed by opposing counsel in any civil or criminal case that might result from the matters currently being audited, and therefore it seemed necessary that you at least be aware that the payments have or are being made," she wrote.

Nienstedt returned the memo with a handwritten note on the side: "This is the first I've heard of this," he wrote. "How do you and Andy suggest we proceed? Please advise."

Haselberger recommended that the archbishop cut off the payments.

Domeier, the former accounting director, told MPR News that Nienstedt already knew about the payments and had approved them every year.

The auditors didn't find every secret deal. And some couldn't be undone. Several priests had signed legally binding agreements with Flynn and McDonough after the national abuse scandal in 2002.

Demonstrators gathered outside the Cathedral of St. Paul before Mass in early October 2013, days after an MPR News investigation that included revelations from former top church official Jennifer Haselberger. Meg Martin/MPR News

Demonstrators gathered outside the Cathedral of St. Paul before Mass in early October 2013, days after an MPR News investigation that included revelations from former top church official Jennifer Haselberger. Meg Martin/MPR News

The final memo

By the end of 2012, Haselberger realized she had failed in her efforts to persuade Nienstedt and his top advisers to change their approach.

Laird suspended Haselberger in December 2012. In a deposition this year, Laird said he suspended her because of a "work conflict" between Haselberger and another employee.

Haselberger viewed the brief suspension as a punishment for her efforts to change how the archdiocese handled clergy sexual abuse cases.

Rev. Peter Laird Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

Rev. Peter Laird Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

In February 2013, she called the Ramsey County Attorney's Office to report alleged child pornography that the archdiocese had found on a priest's computer.

Again, she thought of resigning. And again she hesitated.

"I was very afraid of what would happen when no one was there to raise these questions," she said. "I didn't want to let them win. I didn't want to let that be the church and the archdiocese."

As she anguished over the decision, she kept uncovering new problems.

She wrote a six-page memo on a priest's alleged "sex binges" and theft. She warned of restrictions on the funeral Mass of a priest who had been accused of sexual assault. She investigated a priest for soliciting prostitutes — the archdiocese had learned of that problem when the priest refused to pay his bill and a pimp called the chancery to collect.

Then, on April 30, 2013, Haselberger wrote her final memo to Nienstedt:

"I am informing you that I am resigning my position, effective immediately."

She told the archbishop that it was "impossible for me to continue in my position given my personal ethics, religious convictions and sense of integrity."

"Nothing was going to change." Jennifer HaselbergerJeffrey Thompson/MPR News file 2013

She concluded, "I ask, on behalf of all the members of the faithful of this Archdiocese, that you take your responsibilities toward the protection of the young and vulnerable seriously, and that you allow an independent review of all clergy files, and that you publish the list of all known offenders."

Nienstedt composed a brief reply. "His letter said that he accepted my resignation and that he'd enjoyed working with me, and that was the extent of it," Haselberger recalled.

Events converge

The cover-up was unraveling at the worst possible moment. Two weeks after Haselberger's resignation, the state Legislature passed a law that gave victims of child sexual abuse more time to sue.

Victims' attorney Jeff Anderson had been preparing for this moment for nearly two decades. He filed more than a dozen suits, and the archdiocese consulted with bankruptcy attorneys.

In July, Haselberger contacted MPR News to divulge the church's secrets. She said she had hoped that Nienstedt would have released information on abusers, but since he had refused, she felt that she had to warn the public.

"Now it's not my burden to carry any longer," she said.

Domeier, the former accounting director, told MPR News about the archdiocese's payments to abusive priests.

On Sept. 23, 2013, MPR News published its first report on the archdiocese's decision not to warn parishioners about Wehmeyer. Catholics responded with shock and anger.

Laird met privately with Nienstedt and asked him to tell the public that he had opposed Wehmeyer's appointment as pastor.

Nienstedt refused. A week later, Laird resigned.

The archbishop responded to the scandal with promises of transparency. He convened a task force and hired a firm to review clergy files.

Behind the scenes, Nienstedt faced angry priests.

"Archbishop, you're a liar, you're a thief, you're a coward," one priest told Nienstedt at a private gathering in October, according to a secret recording obtained by MPR News.

-

Listen Nienstedt meets with priests

"Archbishop, you're a liar, you're a thief, you're a coward ... That's what my people are saying."

Nienstedt told priests that he was "blindsided" by the reports of a cover-up.

"We had so many other things happening with the strategic plans and with the Rediscover [outreach] program, and trying to get on top of the financial difficulties that we had, and that's kind of where my focus was," Nienstedt said. "And I presumed that this was being handled correctly, and it obviously wasn't."

After the first news reports, "You just felt like a punching bag, you know," Nienstedt said. "It's one thing coming after another after another."

The archbishop blamed the media. "People in communications say this is probably MPR's one chance to get a Pulitzer Prize, like the Boston Globe did during the Cardinal Law period where they were able to string things together and come up with a kind of a mounting climax of the whole thing pointing blame and that sort of thing."

Nienstedt sought to reassure his priests. "I am on your side," he said. "And it hurts me whenever we have to take steps against a priest because I, like you, hold the priesthood in such esteem. But we're just living in this atmosphere now...I think, in order to reestablish credibility, we have to be able to say we don't have anyone in ministry who is a danger to children or to vulnerable adults."

-

Listen Nienstedt meets with priests

"I am on your side. And it hurts me whenever we have to take steps against a priest."

Nienstedt told his priests that he was trying to be honest and straightforward with them. Within months, however, he would authorize a secret investigation into his private life. In a statement released earlier this month, Nienstedt acknowledged that a law firm had been commissioned to investigate allegations of misconduct against him.

An archdiocese lawyer told Ramsey County Attorney John Choi that the investigation focused on alleged "sexual conduct with an adult," according to a spokesman for the county attorney.

Prosecutors couldn't reveal more because of the "ongoing nature of the overall investigation" of the archdiocese, he said.

Nearly a year into the scandal, though, Choi has refused to convene a grand jury. No one has faced criminal charges. Police have not asked the archdiocese to turn over all of its files. Even today, the church refuses to disclose the names of every priest accused of sexually abusing children.

Ramsey County Judge John Van de North forced the archdiocese in December to release a list of 33 "credibly accused" priests, a disclosure that victims of clergy sexual abuse had requested for years.

Van de North also ordered the depositions of Nienstedt and Flynn.

Under oath, Flynn said he could no longer remember most of the abuse cases, and Nienstedt said his deputies had assured him that the cases had been handled properly.

Nienstedt, Flynn, former top deputies Laird and McDonough, attorney Eisenzimmer and other archdiocese officials declined to comment for this story.

Cheryl and Jeff Herrity Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

Cheryl and Jeff Herrity Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

'Call it what it is'

Nearly 30 years ago, a Catholic couple called Jeff Anderson to report that a priest had sexually abused their son. Anderson's hunt for answers led to the archdiocese's first abuse scandal, in 1987. Archbishop John Roach had pledged healing and urged parishioners and reporters to move on. Meanwhile, in the Diocese of Lafayette, La., Bishop Harry Flynn offered similar assurances.

Every time the church faced another allegation of a cover-up, the cycle repeated itself. Bishops expressed regret and vowed to create tougher policies. Reporters couldn't resist the lure of a strong narrative and wrote stories about how the church had healed.

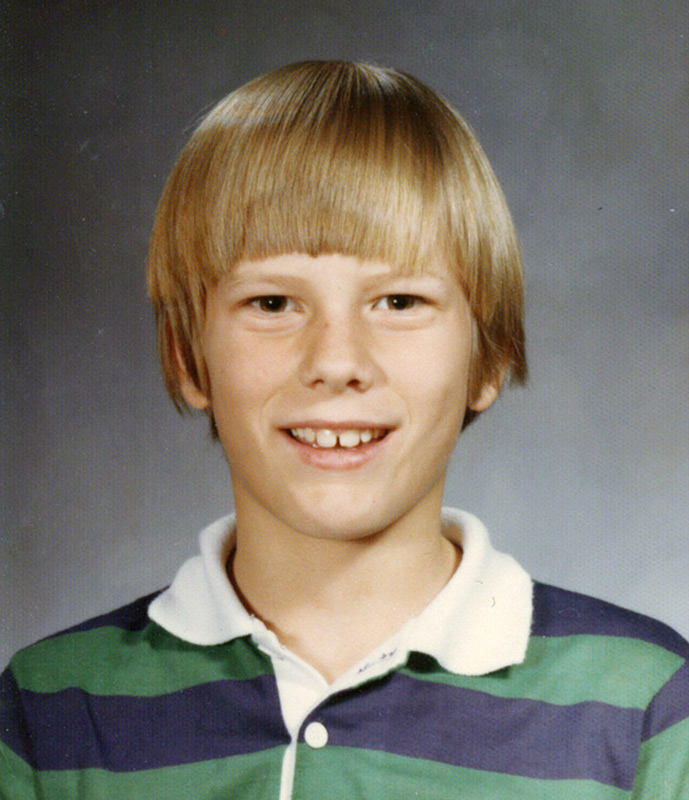

Brian Herrity at about age 9, close to the time when the abuse began. Courtesy Herrity family

Brian Herrity at about age 9, close to the time when the abuse began. Courtesy Herrity family

Meanwhile, church lawyers played hardball with victims and church therapists kept complaints secret. Police didn't investigate, prosecutors showed no interest, and judges sealed thousands of documents.

Priests protected each other, bishops protected the priests, and parishioners didn't demand answers.

Jeff and Cheryl Herrity buried their son Brian nearly 20 years ago. The Rev. Gilbert Gustafson had forced him to perform oral sex on the family's porch while his mother watched TV in the living room. After turning to drugs and risky sex as an adult, Brian died of AIDS.

Cheryl said she's watched as three archbishops have expressed regret and promised to protect children.

She's heard Roach, Flynn and Nienstedt all claim that "mistakes have been made."

And she's sick of it.

"They are unable to tell the truth. Call it what it is: sexual crimes against little children," she said.

This time, she doesn't think the story will be any different: The scandal will fade from the headlines, no one will face criminal charges for the cover-up, and priests who rape children will continue to be protected by powerful men.

"Nothing has changed."

This story was reported by Madeleine Baran with help from Sasha Aslanian, Meg Martin, Tom Scheck and Laura Yuen. It was edited by Eric Ringham. The project's editor is Chris Worthington.

Top photo: The Cathedral of St. Paul at dusk Jennifer Simonson/MPR News

«

Chapter 3

«

Chapter 3  Documentary »

Documentary »