Number of alleged sex abusers greater than archdiocese has revealed

By Madeleine Baran, Minnesota Public Radio

-

Listen

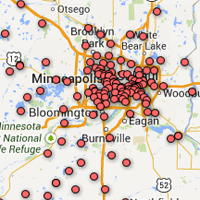

Feb. 19, 2014 An MPR News investigation found the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis has dealt with allegations and suspicions of child sexual abuse involving at least 70 clergy members since 1950.

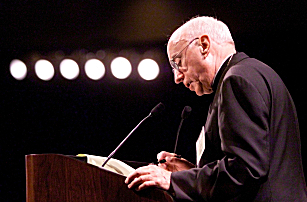

At the height of the national clergy abuse scandal 11 years ago, Archbishop Harry Flynn gave speeches across the country condemning child abuse and vowing to change the church.

Explore the full investigation Clergy abuse, cover-up and crisis in the Twin Cities Catholic church

Meanwhile, the Rev. Kevin McDonough, his deputy at the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis, sat in a chancery office and checked boxes on a form. He was completing the U.S. Catholic Church's first survey of abusive priests.

McDonough selected 33 priests. He wrote down their initials and dates of birth and sent them to researchers. The 33 men became known as the "credibly accused priests." The paperwork McDonough submitted became known as "the list." The archdiocese acknowledged the existence of the list in 2003 but declined to release the names.

• From the archive: 33 priests in Minneapolis Archdiocese abused minors, according to audit (Dec. 11, 2003)

The list symbolized all that victims believed was wrong about the Catholic Church's handling of abuse claims — the secrecy, the failure to warn the public, the hidden offenders. Victims' attorney Jeff Anderson received the list under court seal as part of a lawsuit in 2009. In December, a judge ordered the archdiocese to release the names to the public. The secrecy appeared finished.

But it wasn't. The list of 33 was incomplete. An MPR News investigation has found the actual number was more than double the archdiocese's official count. The priests served in nearly every parish in the archdiocese.

Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's alleged

Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's allegedSearch a database of 70 Twin Cities clergy members about whom MPR News has found allegations of child sexual abuse and other sexual improprieties.

They include men who admitted abusing children, such as the Rev. Gerald Funcheon, who testified under oath in 2012 that he had sexually abused a number of boys. "I couldn't count 'em up," he said. "I'll go, I don't know. I'll go to 18 ... I can't give you a number on this."

Funcheon, who served as a priest of the Crosier religious order, was "permanently removed from ministry" as of 1993, according to the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. He served locally in Anoka, Onamia and St. Cloud, and now lives in Dittmer, Mo. The video above shows Funcheon giving a sworn statement to St. Paul attorney Jeff Anderson.

• Document: Funcheon deposition

Others include a man dismissed from the priesthood for child sexual abuse and several men named by other dioceses and religious orders as credibly accused offenders. One priest left off the archdiocese's official list, who retired from the priesthood at age 53, is now under criminal investigation for alleged child sexual abuse.

The failure to disclose the information led parishioners to believe for more than a decade that the clergy abuse crisis was not as widespread as the media had reported. Top church officials boasted about the number as proof that the archdiocese was among the safest in the nation. The lack of transparency also reduced the risk that a victim might recognize a priest's name and file a lawsuit.

The list of 33, it turns out, was just one of many. There were handwritten lists and emailed lists and memos about lists stored on computers and in filing cabinets at the chancery in St. Paul. Some men appeared on every list, others on one or two. All of the lists obtained by MPR News contain information that police have never seen. Chancery officials later stopped writing lists for fear they could be obtained in lawsuits, former chancellor for canonical affairs Jennifer Haselberger told MPR News.

A review of these lists, court records, private settlements, police reports and hundreds of internal church documents has found that the archdiocese dealt with allegations and suspicions of child sexual abuse involving at least 70 clergy members since 1950.

MPR News also found more than a dozen other priests referred to as possible child abusers in private lists and memos but could find no information about their alleged crimes. MPR News is not naming those men.

Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's alleged

Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's allegedSearch a database of 70 Twin Cities clergy members about whom MPR News has found allegations of child sexual abuse and other sexual improprieties.

Why some men weren't included on the list of 33 is unclear. Documents suggest that in several cases McDonough simply lost track of allegations.

In a November 2005 memo to Flynn, for example, McDonough wrote about the case of the Rev. Kenneth LaVan: "It embarrasses me to acknowledge once again a lapse of memory on my own part. Although I had dealt with LaVan for many years about his boundary violations with adult females, I had forgotten that there were two allegations in the late 1980s concerning sexual involvement with teen-aged girls."

• Document: Read the full memo

In other cases, as the legal stakes climbed, McDonough demanded evidence that was nearly impossible to obtain. In one 2006 case, he rejected allegations from a man who couldn't produce copies of his medical records from the 1960s.

Some of the accused men remain in ministry. Others are long dead. Several have been included on other lists of "credibly accused" priests from other dioceses or religious orders but their assignments in this archdiocese were kept private.

Archbishop John Nienstedt, through a spokesman, declined to be interviewed. McDonough did not respond to an interview request. A spokesman for the archdiocese wouldn't explain how abuse claims were vetted.

Last year, the archdiocese hired Kinsale Management Consulting, a private firm, to review its clergy personnel files. On Monday, the archdiocese disclosed nine more names after MPR News began contacting some of the men.

St. Paul police have not asked the archdiocese to turn over its files on accused priests. Ramsey County Attorney John Choi has told MPR News that he doesn't plan to convene a grand jury. St. Paul Police Chief Thomas Smith has told MPR News he lacks probable cause for search warrants or subpoenas to seize the chancery's files.

• County attorney: Grand jury not a likely option in archdiocese investigation (Dec 16, 2013)

Ramsey County Judge John Van de North is the only public official who has ordered the archdiocese in recent months to disclose some of its information on allegedly abusive priests. It was Van de North who ordered the archdiocese to publicly disclose the names on the list of 33 credibly accused priests. The archdiocese posted the names on its website Dec. 5, 2013, with a disclaimer that said it didn't know why two of the men were on the list.

Van de North also ordered the archdiocese to turn over the names of all priests accused since 2004 of child sexual abuse. The archdiocese said it would appeal.

Private lists and public vows

For more than a decade, top church leaders had promised to be open and truthful about priests who sexually abused children. "We don't have secret abusers out there," McDonough told the Catholic Spirit newspaper in February 2002.

• The Catholic Spirit: "Abuse policy focuses on protection, healing" (Feb. 28, 2002)

McDonough handled abuse allegations for the archdiocese for more than two decades and served as the vicar general from 1991 to 2008. He resigned last year as head of the archdiocese's child safety programs.

When the archdiocese announced in late 2003 that it had found 33 credibly accused priests in the past five decades, McDonough praised his church's handling of abuse claims.

"Our church has been under enormous, enormous scrutiny for the last dozen years," McDonough told MPR News in December 2003. "So I think we probably have fewer unreported crimes than do other institutions."

Keeping the public safe required an aggressive disclosure of the church's secrets, the archdiocese declared in a March 2004 statement. "An evil must be named and defined before it can be successfully confronted," it said.

-

Listen The early list

Dec. 11, 2003 "Audit: 33 priests in Archdiocese abused minors"

And yet, inside the chancery over the past 15 years, secret allegations of abuse have collected in filing cabinets, a vault and the basement archives.

The MPR News investigation found that at least 21 priests named as suspected child abusers by other dioceses and religious orders had served in the Twin Cities archdiocese. At least four priests have been the subject of lawsuits for alleged child sexual abuse but haven't been named on the archdiocese's public list. Records show at least 10 clerics have been criminally investigated.

See the parishes where Johnson and Heitzer served — and learn more about the accusations against them

Heitzer served from Sleepy Eye to Clearwater to St. Paul in his 27 years of ministry. He died at 55 in November 1969.

In one case, MPR News obtained a copy of a $42,000 settlement agreement between an alleged victim of the Rev. James Johnson and the Marist Society, a religious community. The agreement, signed Aug. 13, 2004, said the man could use the money for "counseling or any other purpose that would assist his healing."

The settlement released the archdiocese from all claims. Johnson, who isn't on the archdiocese's public list, served at the Church of St. Louis, King of France, in St. Paul from the mid-1950s to the early 1960s.

• Document: Read the full settlement

Some of McDonough's private memos include troubling references to other files. In a September 2002 letter to a woman who said her brothers had been sexually abused by the Rev. Louis Heitzer, McDonough wrote, "As I have come to learn more about what Louis Heitzer did, I believe he was perhaps the most abusive priest ever to be a part of this Archdiocese. I now believe that he abused boys every place he went." The archdiocese hasn't released any information on Heitzer's alleged abuse. He died in 1969.

Many lists

Haselberger arrived at the chancery in 2008 to work as the chancellor for canonical affairs for Nienstedt. She oversaw the chancery's records and advised the archbishop on the laws of the Roman Catholic Church.

"When I started, the priest files were just an absolute mess," Haselberger said. "So you'd have a manila folder and you'd have everything kind of stuffed in there, from mimeographed papers from way back to copies of letters to memos, just all in this kind of mad jumble, no order whatsoever."

She quickly realized that there was no single list. "We had other lists. Frightening lists, to be honest," she said. "People developed lists based on cases that they were aware of."

Chancellor Bill Fallon compiled one list in 2002 of 16 priests who faced possible removal from ministry for alleged child sexual abuse under a policy known as the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People. He sent the names in a memo, obtained by MPR News, to Flynn, McDonough and Auxiliary Bishops Frederick Campbell and Richard Pates. Campbell now serves as the bishop of Columbus, and Pates serves as the bishop of Des Moines.

Fallon wrote that he had created three categories: one for cases in which the "allegations are admitted and the Charter clearly applies," one for cases in which "the allegations are either disputed or the facts are unclear or unresolved," and one for "those in which the facts are fairly clear, but it is not clear whether the conduct complained of is sufficient to warrant" removal from ministry.

Some of the names on the list are now well known. Two of the men have never been publicly identified as priests accused of child sexual abuse. MPR News isn't publishing the names because no information on the alleged abuse exists in public records or internal documents reviewed for this investigation.

• Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's alleged

Other lists within the chancery from the same time period include an unsigned handwritten sheet of paper with the names of 13 priests alleged to have abused minors and a typed list of 29 priests accused of sexual misconduct with either adults or children.

One priest who was placed on leave last year is included in the handwritten list under the heading "Minors - ??"

McDonough named 27 priests in an Aug. 12, 2002, memo to Flynn.

He divided the names into two categories: "Priests with known abuse histories" and "Priests with disputed claims, marginal behavior, or undue attention." The list includes the names of several priests not disclosed to the public.

Other priests discovered by MPR News didn't show up on any lists, public or private. The allegations against them were written in private memos or letters to victims and leaders of other dioceses or religious orders.

Haselberger said she stumbled across many of them by chance.

"I'd be looking through the file of a priest that had never appeared on any of these lists, and I'd see some kind of report of sexual activity involving a minor," she said.

Haselberger said she notified Nienstedt and his senior advisers of the documents she found and urged them to reconsider whether accused priests should be serving in parishes. In most cases, she said, nothing happened. The documents remained in the files and the priests remained in ministry.

She also recommended that the archdiocese track abuse complaints with a software program called CaseMaster Complaint, used by other Catholic dioceses, Haselberger said. Lawyers and top chancery officials rejected the plan because they worried who would gain access to the sensitive information, she said.

Explore the full investigation Clergy abuse, cover-up and crisis in the Twin Cities Catholic church

By 2013, chancery officials had grown wary of lists. At a meeting with senior officials, McDonough said lists were risky because Anderson, the victims' attorney, could go after them in lawsuits, Haselberger said.

McDonough also sought to dampen the public's fascination with the list in a January 2013 interview with MPR News. "We don't maintain lists… We don't have a list anywhere. I probably could reconstruct a list based on memory or culling of files, but we don't have some secret place where we have a list hung on a wall somewhere."

Haselberger said the lack of an accurate list made it impossible to track accused priests or understand the scope of the problem. "We can't function as a church if our desire is always to protect ourselves from civil liability," she said. "What we should be about is doing the right thing because it's the right thing to do, period."

'Your objection is duly noted'

By the summer of 2012, following the arrest of the Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer for sexually abusing two boys at Blessed Sacrament Church in St. Paul, Haselberger had grown fed up with the archdiocese's handling of abuse cases.

She had warned Nienstedt to reconsider his decision to appoint Wehmeyer as pastor, given the priest's sexual addiction and interest in anonymous sexual encounters with young men. Nienstedt ignored her advice.

Adamson is one of the nation's best-known sexually abusive priests. One of his victims helped St. Paul attorney Jeff Anderson expose a decades-long cover-up by the Twin Cities archdiocese and the Diocese of Winona in the 1980s. Adamson admitted in a 1986 deposition to sexually abusing the boy over several years. He said several bishops knew of his sexual interest in boys as early as 1974. Rather than call the police, they transferred Adamson to different schools and parishes around Winona and the Twin Cities.

• Archdiocese knew of priest's sexual misbehavior, yet kept him in ministry (Sept. 23, 2013)

Haselberger became more forceful in her opposition to the archdiocese's handling of abuse claims. A month after Wehmeyer's arrest, the archdiocese communications department prepared a news release on a lawsuit involving another priest, the Rev. Thomas Adamson. It included three key points for chancery officials to use as background, among them: "No priests credibly accused of misconduct are currently in ministry in this archdiocese."

Haselberger said she believed from looking at the secret lists and private memos that the statement was wrong. In an emailed response, she wrote, "I don't see how we can say that no priests credibly accused of misconduct serve in the archdiocese, even as background. That is simply not true."

The archdiocese's top attorney, Andrew Eisenzimmer, replied, in an email obtained by MPR News: "Jennifer, your objection is duly noted for the record. We go with the statement, as we've done on multiple, earlier occasions, which [Vicar General Peter] Laird has approved."

Haselberger emailed back: "Then please also let the record reflect my concern that when we cause this erroneous information to be published, people make decisions based upon it. Those people include our parish trustees, our corporate board, decision makers at our Catholic schools and institutions, and others who have fiduciary and oversight responsibilities. Those people also include, even more importantly, parents and other guardians who are making decisions about the safety of their children and other vulnerable individuals."

Eisenzimmer did not respond to an interview request.

Haselberger resigned last April in protest of the archdiocese's handling of clergy sexual abuse and approached MPR News with her story in July. Her resignation letter to Nienstedt, which detailed her concerns about several cases, ended with one last request.

"I ask, on behalf of all the members of the faithful of this Archdiocese, that you take your responsibilities towards the protection of the young and vulnerable seriously, and that you allow an independent review of all clergy files, and that you publish the list of all known offenders."

Haselberger said she hasn't talked to Nienstedt since then. She hopes that prosecutors will convene a grand jury and police will seize the chancery's files. Otherwise, she said, no one will ever know the full story.

Shifting numbers

Internal documents don't match the archdiocese's public statements about the prevalence of clergy sexual abuse.

In March 2002, McDonough told the St. Paul Pioneer Press that as of 1998, 15 priests in the archdiocese had been "credibly accused" of child sexual abuse in the past 50 years.

Nearly two years later, in 2004, the archdiocese announced that 26 diocesan priests and seven other priests had been "credibly accused" of child sexual abuse in the past 50 years. All of the abuse took place before 1988, it said. This was the list of 33 that would later become infamous.

Six years later, in an April 2010 interview with MPR News, McDonough offered a lower number: "There are about two dozen names of priests who've been credibly accused in the last 60 years of sexual abuse.

"All of those are known to the public in large group or small, but two that I can think of. In one case, we learned of the accusation through a medical record. In a second case, it was a single accusation against a long-dead priest. And we were able to find no corroborating evidence," he said.

-

Listen 2010 McDonough interview with MPR News

April 5, 2010 "Clergy sex abuse and the response from the Catholic church"

McDonough didn't name the priests but sought to reassure parishioners. "We do not have bad, threatening people, priests or other clergy whose cases are not widely known," he said.

The archdiocese reassured the public that the number of victims was relatively low. In 2004, it said publicly that it had received only 69 credible allegations in the past 50 years.

Yet an internal chancery document from May 2006 — just two years later — lists the names of 180 victims. The nearly eight-year-old document isn't a complete listing of all victims, just those known to the chancery in some depth at the time.

It suggests that the archdiocese could face massive legal liability under a new law that allows victims more time to sue. In the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, by comparison, about 575 people have come forward to allege abuse, and the archdiocese has filed for bankruptcy.

Changing criteria

The jumble of official-sounding language — "marginal behavior," "substantiated claims," "credibly accused" — runs through many of the internal documents without definition or explanation.

Gustafson pleaded guilty in March 1983 to third-degree criminal sexual conduct for sexually abusing a boy, according to Twin Cities news reports. The boy told police that Gustafson sexually abused him about twice a month for six years. Gustafson was sentenced to six months in jail.

Nienstedt, Flynn and McDonough have declined for months to explain how the archdiocese has evaluated claims of abuse.

MPR News could find only four priests who served or worked in the Twin Cities and were criminally convicted of child sexual abuse: Michael Stevens, Gilbert Gustafson, Curtis Wehmeyer and James Porter.

In every other case, the archdiocese relied on its own, unexplained methods to determine whether an allegation was credible. McDonough hinted at some of his personal criteria in notes from a 1988 meeting with an accused priest, John McGrath. The alleged victim's story seemed credible, McDonough wrote, because she made the allegation at the request of a "reputable therapist"; her story included "sufficient accuracy of detail"; she was willing to have her name disclosed to her abuser; and she lacked "personal vindictiveness."

In 2002, Flynn drafted the U.S. Catholic Church's new policy for handling clergy sexual abuse. The Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People said that any priest found to have sexually abused a child must be permanently removed from ministry or dismissed from the priesthood entirely.

In this new era of accountability, the stakes were high and the public pressure intense. Within the chancery offices, officials changed their approach to vetting abuse allegations, according to thousands of documents reviewed by MPR News.

Victims now needed to prove their claims. Church officials created difficult, vague and shifting criteria for an allegation to be deemed credible. It was no longer sufficient for a parent to show up at the chancery in tears.

Most claims of child sexual abuse, in the church or elsewhere, lack direct evidence. There are few fingerprints, surveillance videos or eyewitness accounts. By the time most victims come forward, it's too late for prosecutors to file criminal charges. The horrors of child sexual abuse often remain confined to the memories of victims and the files of their therapists.

Once out in the open, few of those memories could withstand the scrutiny of the archdiocese and its private investigators.

McDonough dismissed some people as too angry to be believed. An anonymous letter alleging abuse by a priest at a campground in the 1970s was dismissed immediately as a hoax, Haselberger said.

For 11 years after Flynn wrote the policy, records show, the archdiocese rejected all but one complaint against a priest not already on the official list of 33. The exception — the Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer — is now at the center of a renewed inquiry into whether the archbishop and his priests broke the law by failing to immediately call police.

A 'priest in good standing'

One of the priests accused of child sexual abuse in the past decade is the Rev. Gerald Grieman, who retired from full-time ministry in 1999 at age 53.

In about 2006, a man told the archdiocese that Grieman had sexually abused him at St. John the Baptist in New Brighton in the early 1990s, when he was about 12 years old.

The man, now 32, asked that MPR News not publish his name.

Gerald Grieman served at churches in Little Canada, Oakdale, New Brighton, St. Paul and Cuernavaca, Mexico, in his 20 years of ministry. He retired in 1999 and now lives in Phoenix, Ariz.

He recalled talking to Greta Sawyer, the archdiocese's victims' advocate, for nearly an hour in 2006. Sawyer listened carefully to his story, the man said, and at first he was hopeful that the archdiocese would seek out other possible victims.

Instead, he said, Sawyer asked him to turn over his psychological records. "She was trying to gather information on my drug and alcohol problems and how troubled of a child I was," the man said.

He declined to provide the records, and the archdiocese decided the claim wasn't credible, he said.

The man's father told MPR News that the archdiocese seemed more focused on finding fault with his family and his son than on investigating his son's claims.

Sawyer told him the case was a matter of "he said, he said," the father said.

The archdiocese did report the claim to the New Brighton Police Department, but police didn't investigate. The father and son said they wondered what happened with the investigation because no one from the police department ever called them.

• Document: Read the police report

They were startled to learn this week that the police report said the case was closed because officers couldn't locate the victim. "Greta knew where to find me," the man said.

Last year, the man contacted police himself to file a report on Grieman. Police closed the case without filing charges, but the case was reopened several weeks ago.

• Document: Read the most recent police report

Grieman, 67, declined to comment. Sawyer did not respond to a request for comment.

In June 2010, Nienstedt wrote a letter to the bishop of San Diego in which he called Grieman a "priest in good standing." Nienstedt wrote the letter in response to a request for Grieman to serve there in the summer.

• Document: Read Nienstedt's full letter

In his letter, Nienstedt noted the abuse claim.

"The allegation was referred to the civil authorities, who declined to investigate due to the incomplete information that was provided," he wrote. "It was then reviewed by an independent investigator, who found nothing to establish or corroborate the allegations. Finally, it was referred to the Archdiocesan Review Board, who saw no reason to restrict Father Grieman's ministry in any way."

Haselberger, the former chancellor, said the review board never looked at the case.

The father of the alleged victim told MPR News that he remains a devout Catholic, but he wishes the church would release all the information on its abuse claims and stop using phrases like "credibly accused."

"They know what they're doing," he said. "If they really wanted to, they could get to the bottom of all of this."

Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's alleged

Accused priests: Who they are, where they've served, what's allegedSearch a database of 70 Twin Cities clergy members about whom MPR News has found allegations of child sexual abuse and other sexual improprieties.

Sasha Aslanian, Lorna Benson, Mike Cronin, Elizabeth Dunbar, Dan Kraker, Meg Martin, Martin Moylan, Eric Ringham, Tom Scheck, and Laura Yuen contributed to this report.