Abusive priest hid in plain sight for years, retired quietly to New Prague

By Sasha Aslanian, Madeleine Baran and Tom Scheck, Minnesota Public Radio

Explore the full investigation Clergy abuse, cover-up and crisis in the Twin Cities Catholic church

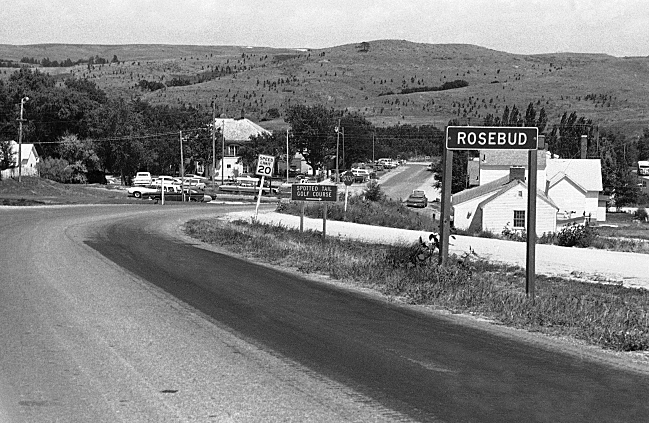

One night on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota nearly four decades ago, a 36-year-old Roman Catholic priest asked a young boy to share his bed.

The boy was about 9 or 10 years old. As he climbed into bed, he asked the priest a question: Are you going to molest me, like my relative does when he asks me to spend the night?

The answer was yes.

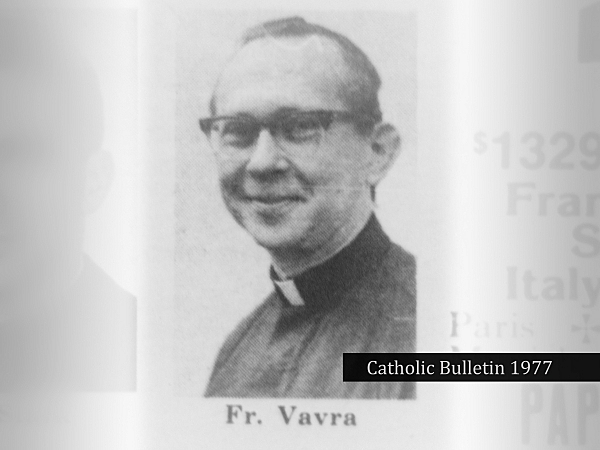

What happened that night remained secret. The priest, the Rev. Clarence Vavra, stayed in ministry and served in 16 parishes in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis before retiring in 2003. He's never been publicly identified as an abuser. There are no records of any police reports or lawsuits. No victims have come forward. Vavra admitted in a May 1995 psychological evaluation that he had attempted to anally rape the South Dakota boy. The report was stored in the vicar general's filing cabinet at the chancery.

• Full coverage: Archdiocese under scrutinyToday Vavra lives in a small, gray home in New Prague, Minn., less than a block from a school. He wouldn't answer questions when approached by a reporter.

New Prague Area Schools Superintendent Tim Dittberner said no one notified the school about Vavra's history of abuse. If the priest had been a convicted sex offender, he said, there would've been a community meeting before authorities decided whether to allow the offender to live so close to a school.

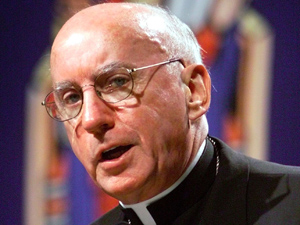

The archdiocese's handling of Vavra reveals decades of deception by leaders who promised "zero tolerance" for sexual abuse. An MPR News investigation has found that three archbishops — John Roach, Harry Flynn and John Nienstedt — failed to report Vavra to authorities or warn the public. Roach transferred Vavra 11 times in 20 years. Flynn overlooked Vavra's alleged sexual interest in a murderer and in a convicted child rapist, and gave the priest payments above his pension in exchange for agreeing to retire early. Nienstedt stopped the payments, but Vavra continues to live a quiet life in a neighborhood full of children.

Nienstedt told MPR News Saturday that Vavra admitted in 1995 to sexually abusing several young boys and a teenager on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. Vavra also admitted to "inappropriate sexual contact with other adult males," Nienstedt said, and received inpatient psychological treatment in 1996.

• The story: Archbishop pledges to release names of priests who sexually abused children"Serious errors were made by the archdiocese in dealing with him," Nienstedt said. "In the spirit of offering him a path to healing and redemption, too much trust was placed in the hope of remedying Vavra's egregious behaviors. Not enough effort was made to identify and care for his victims."

Flynn did not respond to an interview request. Roach died in 2003.

Archbishop John Roach

Archbishop Harry Flynn

Archbishop John Nienstedt

By keeping the abuse secret, Vavra stayed out of prison and the archdiocese stayed out of trouble. Without the name of a priest in the news, it was less likely that victims would come forward to file a police report or a lawsuit. No one had to account for how allegations were handled.

But to keep the name secret was also risky. Minnesota law requires priests to report allegations of child abuse unless they are revealed during confession.

There aren't supposed to be any priests who admitted to sexually abusing children hiding in plain sight. Church leaders have said for years that they don't need to release a list of offending priests because the priests are either widely known as abusers or have died.

Flynn assured the public in April 2002 that he wouldn't hide a child abuser: "I really believe in the zero tolerance, that this person will never have an opportunity again of offending in this way if there's that kind of pathology," he said at a news conference in St. Paul.

Full investigation coverage

Help us tell this story

Contact the reporter

In a statement last month, Nienstedt, who replaced Flynn in 2008, said, "It is critical to understand that our standard is zero tolerance for sexual abuse of a minor or vulnerable adult and absolute accountability."

When confronted Friday with the findings of MPR News' investigation of Vavra, Nienstedt said the archdiocese will release the names of priests who "we know have substantiated claims against them of committing sexual abuse against minors." Some names will be released in November, and more names could be released after a planned review of priest files by an outside firm.

"For the sake of the dignity of each human person and for the sake of our souls, we must fix this problem of sexual misconduct right now," Nienstedt said. "For the sake of the God we love and serve, and for all who are counting on Catholic leadership to live by our beliefs and our word, I will not allow it to stand."

Information about Vavra's abuse and the church's response comes from the archdiocese's former chancellor for canonical affairs, Jennifer Haselberger, as well as internal church documents obtained by MPR News and extensive interviews with a variety of sources, including priests who worked alongside Vavra. The account of the night on the reservation comes from Haselberger's review of a psychological evaluation in which Vavra recounted his sexual history. During the evaluation, Vavra described the incident with the boy and admitted to sexually abusing another child, Haselberger said.

Four internal memos shed light on the archdiocese's approach to Vavra.

"There is absolutely no question" that Vavra violated the church's zero-tolerance policy on child sexual abuse, the Rev. Kevin McDonough, the church's vicar general at the time, wrote in a 2005 memo to Archbishop Harry Flynn. "It was he himself who volunteered that information, and he has confirmed it in subsequent conversations."

The memos show that church officials debated whether to ask the pope to dismiss Vavra from the priesthood because of the abuse. Flynn decided to let Vavra stay if he agreed to retire and do nothing that would identify himself as a priest. Vavra's name disappeared from official directories around 2003.

Vavra has not always abided by the archdiocese's restrictions. He presided over a funeral service last year for a 93-year-old woman in Faribault, according to newspaper obituary that referred to him as Father Clarence Vavra.

Occasionally, the memos show, church leaders wondered whether they had made the right choice. Vavra sometimes didn't want to comply with the archdiocese's monitoring program for abusive priests, although he was offered extra retirement payments as an incentive. He even told McDonough that he couldn't guarantee he would be celibate.

Vavra's problems went beyond child abuse.

At a May 2002 meeting with McDonough, Vavra bristled at questions about his sexual interest in a serial killer named Craig Bjork. McDonough recounted the meeting in a memo to Flynn.

"Mr. Bjork is the multiple-murderer with whom Father Vavra had engaged in 'sex talk' in exchanging correspondence about eight years ago," McDonough wrote. "I wanted to make sure that nothing untoward was going on."

All three archbishops were aided by McDonough, a priest who handled abuse cases for the archdiocese for nearly three decades. They also received help from former Chancellors Bill Fallon and Sister Dominica Brennan, who reviewed priests' files but today say they have no memory of their contents.

McDonough hasn't responded to interview requests.

The revelation about Vavra is the latest chapter in an ongoing MPR News investigation of the archdiocese that has shown how church leaders gave special payments to offending priests, failed to warn parishioners of a priest's sexual addiction and failed to contact police after discovering possible child pornography on a priest's computer in 2004.

The reports have led to the resignation of Vicar General Peter Laird and the departures of Flynn and McDonough from the Board of Trustees at the University of St. Thomas. St. Paul police have reopened a criminal investigation into the child pornography case. And last month, Nienstedt created a task force to review church policies. The archbishop also has postponed a $160 million capital campaign for the archdiocese.

A young priest moved many times

Vavra was born in 1939 in Lonsdale, Minn., near New Prague, a small town settled by Czech immigrants about 50 miles south of the Twin Cities. The landscape is dominated by the massive Church of St. Wenceslaus, a 106-year-old red brick structure with two 110-foot towers on a hill above Main Street.

When Vavra was 14, he enrolled in a junior seminary in St. Paul. His parents and the community applauded his decision to become a priest, and Vavra's ordination in 1965 made the front page of the New Prague Times. A few days later, the editors couldn't resist one more big story: "Rev. Clarence J. Vavra Offers First Mass After Ordination."

Vavra's first assignment was to St. Rose of Lima in Roseville as an associate pastor for three years. It turned out to be one of the longest stops in a career that darted like a pinball from one corner of the archdiocese to another.

He then went to the Church of St. Philip in Minneapolis for a year, followed by a year at the Church of St. Peter in North St. Paul and a year at Guardian Angels Catholic Church in Hastings, which has since merged with another parish. Then came a 12-month unexplained leave of absence, followed by a two-year stint at St. Matthew's in St. Paul.

Many of Vavra's classmates in the 1960s secured more permanent positions as pastors after a few years, according to church records, but Vavra had short-term assignments with sudden departures:

Patrick Wall, a clergy abuse expert and former priest, said Vavra's assignment history raises red flags.

Wall worked in four parishes at the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis from 1986 to 1998 and often filled in for priests transferred because of sexual abuse. Vavra's assignment history, he said, could reveal important clues about the priest's behavior.

For decades, it was common for bishops around the country to move offending priests to new parishes to keep the allegations secret, Wall said. Every new report could lead to a new assignment.

"[They're] moved around quietly and churned throughout the system, and then protected, and kept on the sidelines so as not to come into the light and make the spotlight," he said.

When the national clergy sex abuse scandal erupted in 2002, some of the worst offenders could be identified by the number of pages in their work history.

The Rev. James Porter, who was sentenced to prison for abuse and likely harmed more than 100 children in Massachusetts, Minnesota and elsewhere, was transferred five times in 14 years. The Rev. Thomas Adamson, who's been accused of abusing more than 20 boys in the Diocese of Winona and the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis, was transferred 10 times in 26 years.

Vavra was reassigned 17 times in 38 years. The archdiocese won't say why it moved Vavra so often.

Rev. James Porter

Rev. Thomas Adamson

Rev. Clarence Vavra

On the reservation

In 1975, Vavra went to the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota to work alongside Jesuit priests. It was an unusual move for a small-town priest.

Several priests who served with Vavra there have declined to be interviewed. Two clergy who worked alongside him would later be accused of sexual abuse, although they were never charged.

No one has come forward with allegations against Vavra. The documents obtained by MPR News don't include any names. There are no records of lawsuits or settlements. The young boy described in Vavra's psychological evaluation would be about 47 or 48 years old today.

Psychologist Jeffrey King, a professor at Western Washington University in Bellingham who specializes in the treatment of Native American victims of sexual abuse, said he's not surprised no one has come forward publicly at Rosebud Indian Reservation. He said the general distrust of social workers and police, and the shame that many men feel about same-sex abuse they suffered as children, make it more likely that victims will stay silent. He said many of the families who interact with clergy on reservations find it unthinkable that a priest would be capable of abusing a child. When someone comes forward, he said, it's common for the family not to believe him.

In a document reviewed by MPR News, a man confided to a Jesuit priest in 1997 that he was sexually abused by a priest on the Rosebud Indian Reservation but didn't respond to later attempts by the Jesuits to investigate his claims.

The man told the priest that he couldn't remember his abuser's name but described him as a younger man with glasses who invited him to spend the night and abused him. "I went home the next day but I didn't tell anyone," the man said in 1997. "I thought I did something wrong and would get punished. Now I want to tell my story so he won't do it to other kids." The man declined to be interviewed for this story.

King said it's common for victims to change their minds about whether to come forward.

Child sexual abuse: Get help

Clarence Vavra's brother, Eugene Vavra, said his brother didn't abuse anyone. However, he doesn't dispute that the archdiocese flagged Vavra as an abuser. Vavra left the reservation because he feared for his own safety, he said.

"My mom was sick about it," he said. "She said, 'I don't want him there anymore. He could get killed.' "

The Rev. Ken Ludescher, who served briefly with Vavra at a Maplewood parish a few years later, recalled Vavra's harrowing stories of violence on the reservation.

Ludescher said he doesn't understand why Vavra went to the reservation. In his experience, the archbishop was unlikely to send priests on an assignment outside the diocese unless the priest volunteered. "It would not be a place I'd volunteer to go for the fun of it," Ludescher said. "It seems you'd do whatever to get out of it."

Playing a role

As the national clergy sexual abuse scandal unfolded in early 2002, and bishops came under scrutiny for their handling of abuse cases, Flynn allowed Vavra to remain in ministry for another year.

Vavra's last assignment before retirement was to assist the Rev. George Grafsky at Most Holy Redeemer in Montgomery, Minn., and St. Patrick's Church in Shieldsville. Vavra arrived in mid-1997 after a six-month stint at another parish and took over some of the daily masses for the busy pastor. "As long as he fulfilled that role, I was happy," Grafsky said in an interview with MPR News last week.

Grafsky said he'd heard at the time that Vavra's ministry was restricted in some way because of past misconduct, but he didn't ask questions. "I certainly did not see or hear anything personally or from the parishioners that would lead me to worry about anything," he said.

Grafsky said he doesn't recall whether anyone told him that Vavra had sexually abused anyone. "It's what, 12, 15 years ago? I really don't remember."

Perhaps with a case this old, he said, it's better to keep it private. "I just feel bad that something that happened 40 years ago has to destroy what [Vavra] has done and what he's tried to build up since then," he said.

A meeting about a serial killer

Craig Bjork

In May of 2002, Vavra met with McDonough, the vicar general, to talk about two topics — his relationship with a serial killer and his sexual interest in a convicted child rapist.

Vavra had been caught eight years earlier engaging in "sex talk" with Craig Bjork, a man serving life in prison for killing his girlfriend, his two young sons and another woman.

"When I asked Father Vavra about his relationship with Mr. Bjork, he told me that he has continued to abide by the restriction I put on him. Namely, he is not to write letters to Mr. Bjork and mail them without Father Grafsky first reviewing them," McDonough wrote in a memo to Flynn and Auxiliary Bishop Richard Pates on May 14, 2002. Pates is now the bishop of Des Moines.

McDonough continued: "The most troubling part of the conversation was our return to an old theme, the fellow named Jim, with whom Father Vavra had had a sexual relationship."

Jim was Jim Riley, a man who was serving a seven-year prison sentence in Moose Lake for sexually abusing his son. Vavra told McDonough that Riley was innocent and that he didn't have any "sex talk" with him.

McDonough asked Vavra if he intended to remain celibate when Riley got out of prison. "He said that he was simply not sure that he could promise that," McDonough wrote.

McDonough continued to express his doubts about Vavra but reached what he saw as a practical solution. "Father Vavra is certainly among the most limited of our priests. His intellectual and emotional functioning and his clarity of commitment to Church teaching are all rather marginal. At the same time, his presence permits Father Grafsky, who is a very good pastor, to provide leadership to two parishes and, on occasion, to get away for a vacation and for days off."

McDonough recommended that Vavra, then 63, remain at the parish for two more years and then retire.

A promise

Vavra's departure would not be that simple.

One month later, in June 2002, Catholic bishops gathered in Dallas for their national conference to address the clergy sexual abuse crisis. It was a dark moment for the church. A series of high-profile stories by the Boston Globe had revealed how bishops covered up child sexual abuse and offered little comfort to victims. Parishioners and victims demanded answers.

Flynn emerged at the conference as a leader who would chart the path out of the scandal. He led an effort to draft a new policy of zero tolerance for abusive priests.

The policy, known as the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, said that any priest found to have committed "even a single act of sexual abuse" should be permanently removed from ministry or dismissed from the priesthood entirely.

Bishops returned to their dioceses to make the changes.

At the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis, Chancellor William Fallon reviewed clergy files to determine which priests met the criteria for removal from ministry. Those men became known as the "Charter priests."

Reached last week, Fallon said he doesn't remember who was on the list and can't recall much about Vavra. "Nothing rings a bell with me, other than his name is familiar. I certainly don't remember him as being a priest accused of anything," he said.

At the time that he was pushed out, Vavra negotiated a deal with church officials to retire in exchange for an extra $650 a month in retirement pay, according to church records.

Flynn and McDonough asked Vavra to refrain from saying Mass publicly, from dressing as a priest or doing anything that would indicate that he was still a priest. Vavra moved into his parents' former home in New Prague.

Haselberger, the church official, uncovered Vavra's history of abuse in 2012 when she assisted with an audit that found special payments to Charter priests. She alerted Nienstedt in a Feb. 17, 2012, memo.

"Father Vavra has admitted to engaging in sexual behavior with 9 — 12 year old Native America[n] boys when he was ministering on Indian reservations, as well as with other teenage and adult men under his pastoral care," she wrote.

Documents in Vavra's file indicate his extra payments were supposed to stop in 2004, when he became eligible for Social Security. Instead, they ended last year, when Haselberger uncovered them. Haselberger resigned in April in protest over the archdiocese's handling of clergy sexual abuse.

Vavra's neighbors said they did not know the archdiocese had removed Vavra from ministry for sexual abuse. They thought he had simply retired. Karen Rauschke, a Catholic retiree who lives across the street, said the archdiocese should have warned neighbors. "It's uncalled for and just sad and scary," she said.

In 2005, the archdiocese began a new program to monitor clergy who had sexually abused children or engaged in misconduct. McDonough told Vavra that he needed to meet monthly with the archdiocese's monitor, retired probation officer Tim O'Rourke. Vavra refused. He resented the intrusion into his personal life, particularly when O'Rourke told him that he was not allowed to use the Internet. Vavra finally joined the monitoring program in December 2008, Nienstedt said.

Vavra's brother, Eugene, also clashed with McDonough over the restrictions, some of which he found insulting after the death of their father, Frank.

"I don't know if you know what that feels like, when your father dies, and all his life he's been a priest," Eugene Vavra said. "His mother and dad have been really proud of him, and all this stuff, and then your father dies, and he can't say the Mass or anything. He can't, you know. That's pretty poor."

Annoyed with the Vavra brothers, McDonough suggested that Flynn ask the pope to dismiss Vavra from the priesthood.

"Given that he is balking at any accountability, however, we now ought to ask the Holy See to assist us in taking the next step," McDonough wrote in an Aug. 1, 2005, memo to Flynn. "If you agree with that, then I will ask Sister Dominica to figure out how we go about doing that."

It's unclear why Vavra remained in the priesthood. Flynn had told McDonough earlier that year that he wanted as many of the Charter priests as possible to leave the priesthood entirely and was willing to ask the pope to defrock them against their will, according to an earlier memo by McDonough.

After the clergy sexual abuse scandal in 2002, the Vatican adjusted its procedure to make it easier to kick out abusive priests. Bishops across the country took advantage of the opportunity to ask the pope to defrock their abusive priests.

Although Flynn hasn't returned calls, Nienstedt offered an explanation Saturday for his predecessor's inaction.

The decision "was based on a desire by the archdiocese to be responsible for such men, versus placing them outside of the Church and unsupervised as lay citizens who would have no restrictions," Nienstedt said. "There was an earnest effort to be responsible."

The former friend remembers

The archdiocese's failure to take more aggressive action against Vavra left him feeling emboldened, said the priest's former friend, Jim Riley.

Jim Riley

Riley denied any sexual relationship with Vavra and said he was wrongly convicted of his own sex crime. He met Vavra in 1988, he said, while seeking advice on an annulment, and received support from Vavra while he was in prison.

He said he stopped talking to Vavra about a year ago because of Vavra's sexual advances and because he began to doubt Vavra's claims that he had done nothing wrong. He now believes Vavra is a child abuser.

"Sometimes he said, 'Well, it just came out of an act of love, so it was OK,' and that, to me, that's not right. 'Act of love,' it doesn't make a difference," Riley said.

Riley said Vavra was angry about the restrictions the archdiocese placed on him, but agreed to go along with them for the money. He recalled watching a TV news program on clergy sexual abuse several years ago; Vavra commented to him that the victims just wanted money from the church.

"It seemed to me that he always blew it off, like, 'Well, it ain't no real big deal,' " Riley said. "The church would probably give him that feeling because every time he got caught, they'd move him around somewhere."

Mike Cronin and Meg Martin contributed to this report.