Thousands in back taxes ride on one question: Is Venus de Mars a professional or amateur artist?

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

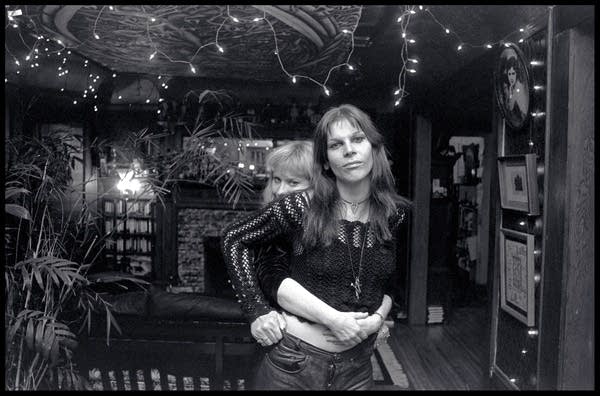

Venus de Mars has been a longtime fixture in the Twin Cities music scene, producing seven original albums over the past two decades. Known for provocative stage shows that involve lots of black leather and reverb, the transgender rock musician tours regularly around the country, singing songs inspired by her experience living between genders.

De Mars does not have a day job. She makes about $20,000 a year entirely on her music, painting and other artistic endeavors and considers herself a professional artist.

The Minnesota Department of Revenue, however, disagrees. Its ruling earlier this year defining de Mars as a hobbyist who cannot claim tax deductions for her artistic work could set a precedent that advocates for artists say would put artists' careers in jeopardy.

Since the 1990s de Mars, who goes by "she," has employed an accountant to file her taxes, claiming deductions on work related expenses under her legal name Steven Grandell.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Late last year, state tax officials audited de Mars and her wife, poet Lynette Reini Grandell, for the years 2009, 2010 and 2011. After more than six months of paperwork and interviews, the Minnesota Department of Revenue ruled that de Mars is not a professional artist.

It listed several reasons, chief among them that de Mars took too much pleasure from her work, and didn't work hard enough to make a profit. As a result, state officials say she owes thousands of dollars in back taxes.

PROFESSIONAL VS. AMATEUR

At issue in de Mars' case is how the Minnesota Department of Revenue determines who is a professional artist and who is an amateur.

De Mars vigorously disputes any notion that she is not a professional.

"It's crazy — I have a studio, I have transportation costs, and I have costs in putting out my product and I don't have another job," de Mars said. "So, profit is important to me because that sustains me as an artist. I have to make a profit in order to continue working as an artist, and I've been able to do that for 10 years."

Although de Mars did not make a profit in any of the three years audited, she did make a profit the following year, 2012.

When de Mars goes on tour, she often sleeps at the house of a relative or friend. To de Mars, that is being frugal, but the Department of Revenue saw it as evidence that she was merely expensing a vacation.

Independent filmmaker and television producer Emily Goldberg, who spent a year and a half filming de Mars and Grandell for the for the documentary "Venus of Mars," said it's absurd and outrageous to think of de Mars as merely a hobbyist.

"If Venus isn't an artist, I don't know who is," Goldberg said. "She paints, she writes, she writes poetry, she writes prose. Music is going through her head all the time. She is living, breathing, dreaming art. And to say that Venus is a failure as an artist is just a horrible statement to me because she above all succeeds with what she does. She gets her message out, she makes her records year after year after year, she creates art and why is she getting punished for that?"

As an artist, Goldberg worries about the wider ramifications of de Mars' case.

"If Venus can be singled out like that, who's going to be next?" Goldberg asked. "It just seems like the state is singling out artists for no good reason, and that's scary."

LAW OPEN TO INTERPRETATION

Minnesota Department of Revenue Assistant Commissioner Terri Steenblock would not comment on the specifics of de Mars' case. However, she said that when state auditors try to determine whether someone is a professional or a hobbyist, they take several factors into consideration. Among them, she said, are the deductions artists list and what their motives for listing them might be.

"We can't just go by feelings," Steenblock said of how auditors work. "It's all based on facts and making sure that each taxpayer, regardless of what industry they're in and what they're doing, that everybody is treated equally and given the same opportunity."

But not everyone believes the Department of Revenue is giving equal treatment under the law.

Lynda Mohs, who has been preparing taxes for artists in the Twin Cities for more than 40 years, said only 5 percent of tax law is clearly defined. The rest, she said, is very open to interpretation. For instance, one rule of thumb is that to be a professional, an artist must have made a profit at least three out of five years. But Mohs said that is just a guideline, not a hard and fast rule.

"A lot of artists don't make a lot of money until after they've been dead a long time, and then their artwork becomes way more valuable," Mohs said. "So just because an artist didn't make money for three years, you can't say it's a hobby, or he didn't try — you have to look at intent. Was the intent to make money or was the intent to sit around and play music?"

While she's not de Mars' accountant, Mohs took a look at the Minnesota Department of Revenue's judgment on the case. In one year, de Mars had $15,000 in income, but $25,000 in expenses. Because of the state's ruling, de Mars is now expected to pay taxes on the income without being able to file any of the deductions. For the three years that she and Grandell were audited, de Mars owes a total of $3,535. If the IRS follows the state's lead, de Mars will owe more than $10,000 in taxes. Mohs said the Department of Revenue is "playing dirty pool."

"They target people with very low income that they think can't afford and won't be able to fight them," Mohs said. "And they'll target a whole bunch of these lower income people to set precedence in something like this."

At one point during the audit process, de Mars said, the Department of Revenue offered a settlement. If de Mars agreed to sign it, she would only have to pay a fraction of the money owed in exchange for not pursuing legal action. De Mars declined, which appeared to surprise the auditor.

Mohs said that's a common practice employed by the Department of Revenue to ensure that a case doesn't go to court.

"They don't want this in front of a judge," she said. "It's kind of like bribery or black mail and I don't like it but they use it."

De Mars plans to take the case to court. For Mohs, it's important that de Mars is taking the Department of Revenue to court to hold it accountable for its decision. Otherwise, she said, the department's ruling in the case could set a damaging precedent for other Minnesota artists.

For its part, the Department of Revenue declined repeatedly to respond to any allegations by de Mars and her supporters. Steenblock would only say that taxpayers who disagree with auditors decisions could file an appeal, contact a taxpayer rights advocate, or appeal to tax court.

On Saturday, De Mars and other musicians are performing at Triple Rock in Minneapolis to raise money for the legal battle.

Editor's note (July 22, 2013): An earlier version of this story misidentified the name and title of the Minnesota Department of Revenue's assistant commissioner, Terri Steenblock. The story has been updated.