'Slavery By Another Name' documentary has Minn. connection

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

A new documentary to be broadcast tonight, produced partly in Minnesota, shows how thousands of African Americans were imprisoned on trumped-up charges after the Civil War and leased to the owners of factories, farms and mines as slave laborers.

MPR's Cathy Wurzer discussed the documentary, "Slavery By Another Name," with author Douglas Blackmon and executive producer Catherine Allan. The film is based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Blackmon and was produced in conjunction with Twin Cities Public Television. It airs on PBS stations around the country tonight.

An edited transcript of the interview is below.

Cathy Wurzer: The history most of us read, of course, indicates that the tough laws passed post-Reconstruction, the prison laborers, and then later the chain gangs, stemmed from the high crime rate among African Americans — with the narrative that these folks didn't have the social or cultural tools to handle freedom. But your research busts that myth. As a Southerner, what did you think when you first discovered this?

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Douglas Blackmon: Well, it became really apparent really fast that that was this essentially made up story about what had happened after the Civil War. But when I first began the really hardcore research into all of this, one of the main questions that I had to answer was that it was clear that all of a sudden the South had gone from this place where there were no black people incarcerated — because slaves had been under the purview of their ostensible owners, so there were no black people in prison or being arrested for the most part — to this place that had this massive population of black people being held by the state and sold into this labor situations.

So the real question was: Is this a story about a criminal justice system in which criminals are being punished really harshly and maybe too harshly? Or is this a story about free and innocent people who committed no crimes, by and large, being swept up into a system that exists specifically to provide for (slave owners) and it really has nothing to do with whether crimes are occurring or not?

And so the first question was, 'Which is it?' because those are very, very different stories. And as I began to research, even I, as someone who had been paying attention to some of these sorts of things for a long time and was open to alternative explanations, even I was fairly astonished when I put it together, basically by going county by county and finding the criminal arrest records and the jail records in county after county after county from this period of time and seeing that if there had been crime waves, there had to have been records of crimes and people being arrested for crimes. And in reality, it's just not there.

There's no evidence that that ever happened. In fact, it's the opposite. The crime waves that occurred by and large were the aftermath of the war and whites coming back from fighting in the Civil War and settling scores with people and all sorts of renegade activity that didn't involve black people at all, but they were blamed for it, and that was then used as a kind of ruse for why these incredibly brutal new legal measures then began to be put in place.

Wurzer: One of the protagonists in the book and in the film, he's prominent, is Green Cottenham. He was a young black man who was a convict leased out by the state of Alabama who was worked to death in a coal mine. Why did you focus on him when there wasn't much evidence of his existence? There were no photos and very little written documentation.

Blackmon: That name stuck out — Green Cottenham. And of course, in all historical research, it's much easier to work on distinct names than common names. And so I inserted Green into the story, but they I spent about a year trying to put together his life and a narrative of his life and realized that there was so little information that I abandoned him and decided I just can't go that way and went another direction for about a year. But then began to realize, no I've got to go back to Green Cottenham because he represents what so much of this is really about — and that was the number of people who essentially had their lives extinguished, both physically and literally their lives ended by these practices, but because of their poverty, because of the degree to which society didn't care about these people, that nobody in America really cared that these things were happening at the time, that their very existence was nearly lost.

And so for me, he became representative of that, and I made a very deliberate decision that I couldn't be part of the conspiracy to lose him from history, and instead had to do the opposite.

Wurzer: Catherine Allan, you've dealt with documentaries in the past where people are long since gone. In the case of Green Cottenham, not only has time forgotten him, no one even knew him to begin with. So how do you bring this person to life with video?

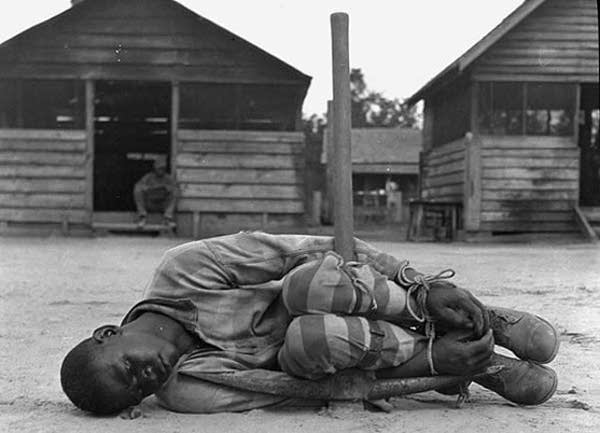

Catherine Allan: It was really a challenge because there were no photographs of him. There were lots and lots of photographs of anonymous prisoners. And the documentary is full of ... amazing documentation of forced labor in coal mines and brick factories and turpentine farms. All over people were snapping pictures, but they're all anonymous. You don't know who any of the people are.

And so with Green, we thought we would use actors on camera and do re-enactments that would bring him to life, and that was good. That really helped visualize what it was like to be arrested, picked up for vagrancy, and you see a young man just being hauled off and sent off to work in a prison camp, and of course see some of those conditions, all of which we did through a combination of re-enactments and photographs.

Wurzer: You had another re-creation in the film of a prison laborer, Ezekiel Archey, who wrote letters to inspectors about his plight in the Pratt coal mine, which was a miserable existence. Where did you find his letters?

Blackmon: Ezekiel Archey was a young African American man, born in slavery, who then experienced emancipation in his childhood, but then was sucked back into the system by the 1880s. And we don't really know a lot about the context of his letters, but he began writing letters to the prison inspector of Alabama. It's one of the very few primary source voices from that period of time from a witness actually inside these coal mines and inside these conditions. And his letters are extraordinarily despairing and poignant.

Wurzer: How did you use those letters and then work off of them, when it comes to creating a film?

Allan: Well, we found a wonderful actor, the producer/director Sam Pollard cast a wonderful actor to portray him and used this technique of speaking right to the camera as he speaks the words from his letter and sort of intercut his scenes with descriptions of what actually went on in the mines. And actually, we also intercut a scene with a descendant of the guy who whipped him and whipped other people in the mines. And so we sort of tried to build a collage with descendants who are living today and historical characters.

"Slavery By Another Name" airs tonight at 8 p.m. on PBS.

(Interview edited and transcribed by MPR reporter Madeleine Baran)

Dear reader,

Your voice matters. And we want to hear it.

Will you help shape the future of Minnesota Public Radio by taking our short Listener Survey?

It only takes a few minutes, and your input helps us serve you better—whether it’s news, culture, or the conversations that matter most to Minnesotans.