Music in the midst of Sri Lanka's civil war

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

One of the stories of 2009 was the end of 25 years of brutal civil war in Sri Lanka. Government troops forced the surrender of the Tamil Tiger rebels in the island nation just south of the Indian continent.

One Minnesotan who got an inside view of the conflict was journalist Jesse Hardman In the midst of the chaos he came upon an amazing story of a forgotten people.

Jesse Hardman went to Sri Lanka to train and lead a team of local journalists. They travelled the length and breadth of the country, talking to some of the tens of thousand of people in displacement camps.

These were people pushed from their homes by outbreaks of violence, often at a moment's notice. Some had been out of their homes for months. As Hardman's news team came into each community they set about spreading information the people desperately needed.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"Kind of visiting their situation, learning from them what their needs were and then tailoring a newspaper, a radio show, to their information needs," Hardman said.

They sometimes even set up text messaging services, as Sri Lankans now get most of their news through their mobile phones.

During one of these trips Hardman's driver surprised him by announcing they were approaching the Kaffir community. Kaffir is a name which in some parts of Africa carries the same nasty overtones as the n-word. However the driver assured Hardman this was where a group calling itself the Kaffirs lived.

"And I swear to God, 10 minutes later we were knocking on a door, and out came a 6-foot-5-[inch] man of African descent in a sarong, no shirt," Hardman said. "And my staff were shorter Sri Lankans, this man was enormous, and they literally fell on the ground."

Hardman said he learned that this man was a descendant of African soldiers brought to Sri Lanka six centuries ago.

"And then over time they stayed and intermingled with the local population a little bit," Hardman said. "They are Catholic because of the colonization by the Portuguese."

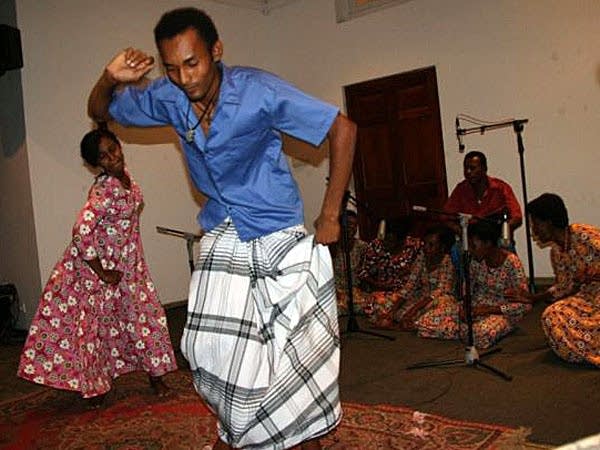

Another thing Kaffirs had retained was their music, called Manja.

"It's kind of a creole of African and it's sung in Portuguese, a Portuguese creole," Hardman said. "They don't speak their language any more, but they can sing, and so that's kind of the connection."

The musicians used very basic instruments: drums, coconut shells, spoons, even coins clinked against bottles. The sound captivated Hardman and his news team. Every song was accompanied by a dance.

Jesse Hardman realized this was an opportunity to bring people together in the midst of a civil war.

"I mean literally there are maybe one or two people we found that had done any sort of research or had much understanding of them so it's as close to a forgotten community as I have ever come across."

"I mean so much war and pain and struggle, I think you begin to lose your sense of what makes you great, and what make Sri Lanka great at least from an outsider is the diversity there," he said.

And here was a centuries-old community which very few Sri Lankans knew about. Hardman came up with a plan.

"Since I am talking to a Minnesota audience, I'll just say, I stole 'Prairie Home Companion' and put on a version in Sri Lanka at a U.N. displacement camp," Hardman said.

The show wove together the Kaffirs songs with live interviews with United Nations officials. They offered information about resettlement aid and other details useful to the 10,000 people in the camp.

Some 500 people came to the broadcast. It was such a success Hardman and his team took the Kaffirs to the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo where they did another concert, this time in a music club.

It was there Hardman saw something he still is trying to get his head around. After the concert it seemed everyone in the club came backstage to greet the artists, including a friend of Hardman's from Gabon in west central Africa.

"And when the Kaffir women saw him, this African guy, they just circled around him and started touching him. He didn't say a word. He was crying," Hardman said. "It was this amazing like - I don't even know how to describe it.

"They hadn't met a real African. He felt he was meeting someone from his world that had been displaced or taken away, on such a deep level that you or I could never even fathom."

The Kaffir's ancestors crossed the ocean in the 1500s. Jesse Hardman said they would be lost in Africa today. Yet in that room in Colombo, 600 years of separation evaporated.

That was in November 2008, and a lot has changed since then.

The Sri Lankan Army moved in and subdued the Tamil rebels. There will be a presidential election in late January, and Hardman worries things could turn nasty.

He's back in the U.S. and fell afoul of the Sri Lankan authorities when he helped a British newspaper set up an interview the authorities didn't like. They withdrew his visa and 36 hours later he was on a plane to Thailand.

The Kaffirs continue to perform in Sri Lanka. The concert Hardman and his crew recorded in Colombo has become a CD. Hardman sent most of the discs to the Kaffirs so they can sell them. While he knows there could be downsides to drawing attention to the group, he thinks it's good people now know about them.

"I mean literally there are maybe one or two people we found that had done any sort of research or had much understanding of them so it's as close to a forgotten community as I have ever come across," Hardman said.

Jesse Hardman believes his news team made a difference. Studies found the information they provided helped some of the displaced people find better conditions. He'd like to go back some day, but he said he knows that's unlikely to happen for a long time.