Pesticides touch more than crops

A Minnesota Department of Agriculture official says it appears this is the first time anyone has used drift catcher technology to monitor pesticide use in Minnesota.

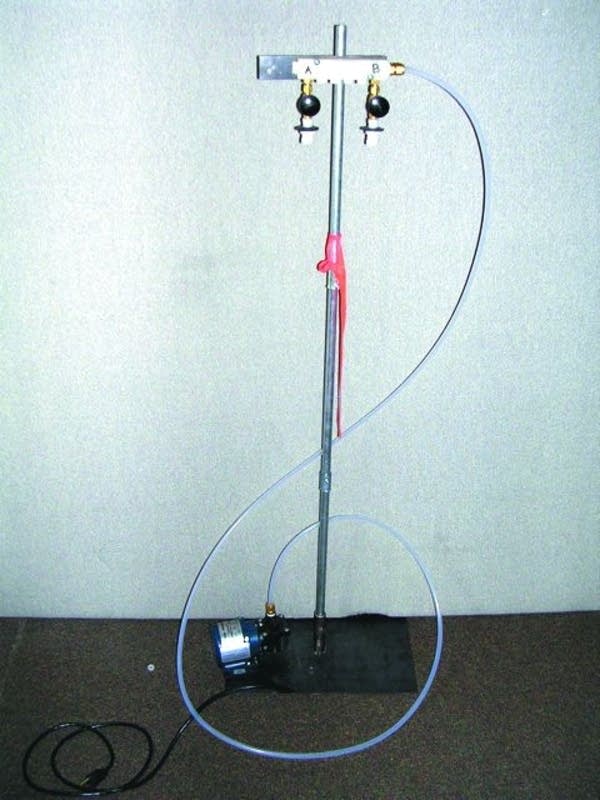

Several Minnesota citizen groups joined forces with the California-based Pesticide Action Network North America to set up 11 mechanical devices called drift catchers which measure how much pesticide drifts from farm fields.

The monitors sample the air and chemicals are trapped in a resin. That resin is then sent to a laboratory for testing. Samples are collected each day.

"The contamination was as high as 10 out of 10 days, 7 out of 11 days, 12 out of 13 days, 8 out of 8 days. So we have a problem," says Bob Shimek, and organizer for the Bemidji based Indigenous Environmental Network.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Some of the drift catchers were located on the White Earth Indian Reservation, others were near Browerville, Staples and Frazee.

Many were located near potato fields and over the past two summers the drift catchers detected several pesticides, but the most often found was chlorothalonil, a common fungicide used to prevent potato blight.

Monitoring data shows chlorothalonil was found in two thirds of air samples tested.

"Just on chlorothalonil, the one they use on potatoes, the air was contaminated in 123 of 186 samples that were tested. So that's a pretty disturbing track record that's starting to emerge for this particular ag chemical, " says Shimek.

The monitoring samples were tested in the Pesticide Action Network North America (PANNA)lab, with some samples also tested by an independent laboratory according to PANNA Staff Scientist Karl Tupper. Minnesota residents were trained by PANNA to collect samples from the drift catchers.

"We kind of look at it like a police investigation, where you have to get out there and collect as much data as you can to put together the most solid case that you can."

This is preliminary data, according to Bob Shimek, who says early results point to the need for more monitoring, something he expects to happen next year. Shimek says it's important to know how widespread pesticide is because of potential human health risks.

Some of the fields near the drift catchers raise potatoes for the R.D. Offutt company, the nation's largest producers of potatoes.

R.D. Offutt Senior Agronomist Dale Steevens says he's aware of the drift monitoring project, but has not yet seen the results. Steevens says pesticide drift is a concern because the company applies pesticides by airplane, ground sprayer, and through irrigation systems. In each case, Steevens says, the company follows best management practices established by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

He says those methods of applying pesticide are designed to prevent pesticides from drifting away from the field where they are applied.

"We do things to minimize the potential for it. If there is a product then that is above levels that are safe, we need to look for alternatives. And there are more alternatives becoming available to us," says Steevens.

Steevens wants to know if the pesticide drift exceeds safe levels, but that will be a difficult question to answer, because the government hasn't set a safe level for chlorothalonil in the air. The drift catchers found a wide range from barely detectable, to extremely high, levels of the pesticide.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)lists the chemical as a likely carcinogen and says the chemical is most toxic when inhaled. But the agency doesn't say what level is safe to inhale over days or weeks.

The EPA declined comment on pesticide drift monitoring. An agency spokesman says the issue and technology is currently under internal review.

Minnesota Department of Agriculture spokesman Mike Schommer, says drift catchers are relatively new technology and the department has limited knowledge of how they work. But he says any new monitoring technology that's effective and accurate will help improve how the agency enforces pesticide regulations.

"We kind of look at it like a police investigation, where you have to get out there and collect as much data as you can to put together the most solid case that you can. And that way if you need to take legal action you've got solid evidence and it will stand up in court," says Schommer. "Anything we can do to provide good data, and certainly this technology sounds like it might help with that."

Schommer says the state's agriculture department was not asked to participate in the pesticide monitoring, but the agency is eager to see the research findings.

Bob Shimek says the apparent widespread pesticide drift means the monitoring will need to be a long term project. He says he hoped for a different outcome.

"I was really hoping that everything was and is like the farmers and chemical companies and regulators say it is, as in these pesticides stay where they are applied. That is what I was really wishing we could have had. But as we now know, that is not the case," says Shimek.

The pesticide drift research will be presented to the Minnesota House Environmental Justice and Healthy Housing Subcommittee at a hearing October 18 in Wadena.