First leg of Petters trial gets underway

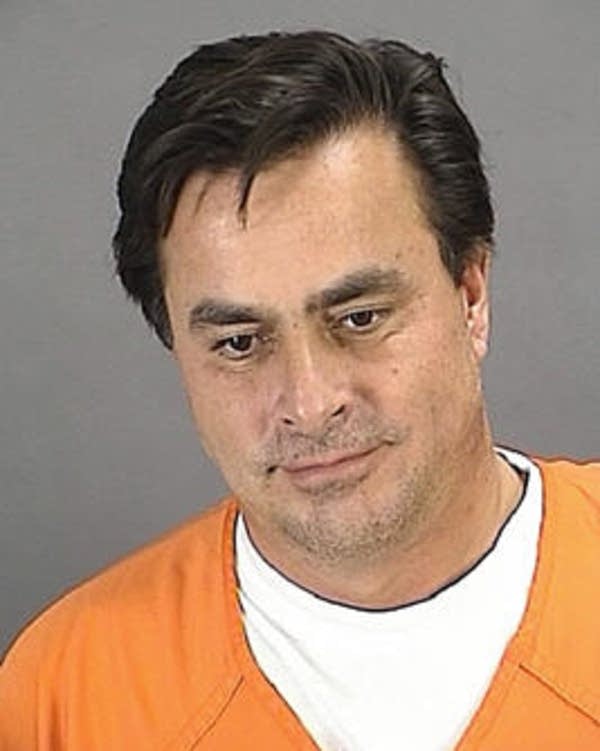

The trial of businessman Tom Petters, who stands accused of running a Ponzi scheme that cheated investors out of some $3.5 billion, gets underway Wednesday with the selection of jurors.

Not much more than a year ago, Tom Petters was still being hailed for turning around failing companies like Fingerhut and Sun Country Airlines. Petters' combined enterprises had billions of dollars in annual sales and some 3,200 employees, and he shared his good fortune, giving millions of dollars away.

In an address at the University of Minnesota's Carlson School of Business in August 2008, Petters explained the reasons behind his success. The title of his speech was "Connecting the Dots."

In her introduction of Petters, business school dean Alison Davis-Blake noted the wide respect Petters had won.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

A great humanitarian. A great business person. Please join me in giving a warm welcome to Tom Petters," Davis-Blake said to the assembled crowd.

Petters spoke of the need to learn what we don't know and grasp what is not so obvious, and to practice -- not just preach -- ethical behavior.

"Integrity. That's not something that we want to aspire to," Petters said. "Without trust, you really can't do anything."

Petters won the trust of many people, and federal prosecutors say he betrayed them for more than a decade.

The feds say Petters convinced investors to give him billions of dollars, promising fat returns on the money. The government says Petters told investors he used their money to buy merchandise that he would then resell at a profit to big retailers. That wasn't what was going on.

In reality, prosecutors say the money went to pay off other investors, to buy and prop up Petters' collection of businesses, and to fund his lavish lifestyle.

In September 2008, a longtime Petters employee went to the U.S. attorney and exposed the alleged investment fraud, which was fast falling apart. That employee -- Deanna Coleman -- and six other of Petters' business associates have pleaded guilty to taking part in the Ponzi scheme, and they've agreed to help nail Petters in court.

Petters has been in jail for more than a year and the government contends he'd likely flee if he were free.

Petters says he's innocent and his lawyers have signaled they'll attack government witnesses as crooks. They've said they'll try to pin the blame for the financial fraud on others.

One former business associate who could testify against Petters, Larry Reynolds, is certainly no choir boy. Court documents and newspaper articles from the 1980s indicate Reynolds is really Larry Reservitz, a disbarred lawyer and convicted felon who betrayed an east coast organized crime group.

Before he met Petters, Reynolds had been given a new identity in the federal government's witness protection program.

That history could help Petters. But jurors shouldn't expect all the witnesses against Petters to be saints.

"When you have unsavory cooperating witnesses, prosecutors tend to say something to the effect that you don't find many swans when you go swimming in the sewer," said John Radsan, a professor at the William Mitchell College of Law and a former assistant U.S. attorney in San Diego.

Radsan said prosecutors can simply note they're putting on the stand people Petters choose as friends, employees and business partners. But Radsan said it's critical for the government to provide evidence that backs up what those people say.

"It's especially important to corroborate cooperating witnesses because juries don't like snitches," Radsan said. "But they will believe snitches if they find out by other documents, records and recordings and even other witnesses that what the cooperating witnesses are saying is true."

Veteran defense attorney Earl Gray is just an observer in the legal battle, but he said the prosecution could be vulnerable because of the character of its witnesses.

"If you can make the co-defendants more despicable than your client, and establish your client was just an honest businessman that got corrupted by these fellows, you might have a shot," Gray said.

The government's case appears to be strongly supported by many taped conversations and a long trail of electronic and paper documents. Gray said Deanna Coleman's decision to turn herself in gives her credibility.

"Her testimony is going to be tough to overcome," Gray said.

But strange things can happen in a court room. University of St. Thomas law professor Lyman Johnson said great cases don't assure victory.

Lyman cited the example of Richard Scrushy, of HealthSouth fame.

"Five chief financial officers of HealthSouth pled guilty, and all testified against Mr. Scrushy," Johnson said. "The prosecution had wonderful evidence, but Mr. Scrushy was found not guilty."

That was just one trial for Scrushy, though. The HealthSouth CEO was convicted in a subsequent criminal trial and sentenced to prison.

Petters' alleged victims range from nonprofit social service organizations to big hedge funds.

Richard Feldman of California invested with a Florida firm that claims Petters owes it $1.1 billion.

"I was definitely fooled by this man and the people that he fooled," Feldman said.

Feldman doubts he'll get anything back.

"Basically, the investors are left with suing the insurance company, the bank [and] Palm Beach management," Feldman said. "I have to say that after all this time; I don't think there'll be anything."

Actually, there is some money for victims. Court-appointed receiver Doug Kelley has raised $200 million by selling assets of Petters, as well those of co-conspirators who've pleaded guilty. And Kelley hopes to raise a half-billion dollars more.