American Indians prefer to reflect on their own history

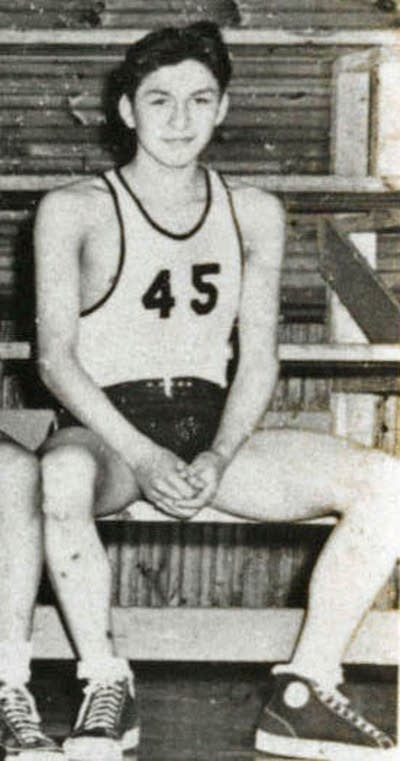

Peter Strong is a thin, quick-witted man with salt and pepper hair. He sits in his office in Red Lake, where he works as the tribe's property officer.

Strong grew up in the 1930s, when there weren't many jobs on the reservation. He says most people were dirt poor, and many didn't have electricity or running water. But the lake provided plenty of fish and the forests were full of wildlife.

"We pretty much ate off the land, you know?" said Strong. "Partridges and deer started around Sept. 1. Rabbits -- we had rabbit snares out there. And then fish. Short ribs and hamburger was almost unknown in those days."

While hunting and fishing traditions were strong in the 1930s, the Ojibwe language was already fading. Strong avoided boarding school, but his grandfather and others in his family were sent away. He says his parents decided that teaching him Ojibwe was a waste of time.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

"They didn't try to teach us because they wanted us to speak English and go to school," Strong said. "(They'd say) 'You're going to have to learn the ways and compete with the white man.' It was the right way to do it at the time. Learning to speak Indian wasn't going to get us any job, you know?"

Strong may have lost his language, but he's held on tight to other parts of the culture. He's been going to powwows since before he could walk, and he still dances and sings traditional songs. Some songs are hundreds of years old, while a few he learned from his father and grandfather, who wrote their own songs.

Like many people on the Red Lake Reservation, Strong knows where his ancestors came from. The Ojibwe people once lived on the east coast. Even before the arrival of Christopher Columbus, they began a slow migration westward. By the 1720s, Ojibwe families landed on the western shore of Lake Superior and began moving into northern Minnesota.

"They didn't try to teach us (Ojibwe) because they wanted us to speak English and go to school. And you're going to have to learn the ways and compete with the white man."

For the next 130 years, the Ojibwe had fierce battles with the Dakota Sioux tribe who already lived in the region. Most Sioux families eventually moved out of northern Minnesota into the Dakotas. Strong says his paternal great-grandfather was among the last Red Lake men who fought against the Sioux.

Strong's maternal great-grandfather has a much different history. He was a Scotsman named Joe Oman who came to Red Lake from Canada. Oman took refuge at Red Lake following his involvement in a political and military conflict in Canada known as the Riel Rebellion of 1869. Oman and a tribal woman had a son together in 1872 named Peter Graves, Strong's grandfather.

Strong says his grandfather was sent away to boarding school in Philadelphia and came back to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

"Peter Graves learned to speak English and write and read and whatever else they taught him over there," said Strong. "He came back and got a job with the BIA as an interpretor and eventually became chief of police."

Graves went on to become chief of the Red Lake tribe. He provided leadership at a time of great change for Ojibwe in Minnesota.

In 1950, when Graves was 78 years old, he was interviewed by the Minnesota Historical Society. He talked about the Battle of Sugar Point, an 1898 conflict between the federal government and the Leech Lake Ojibwe south of Red Lake. That skirmish is considered the last major battle between Indian tribes and the U.S. Army. Graves tells his interviewer the Red Lake tribe was nearly drawn into that conflict, but he convinced them not to go.

"They were going over to Sugar Point to help the Leech Lake Indians in that fight," said Graves. "When I heard what they were saying and they were ready to go and so on... I told them that anybody that goes and helps the Leech Lake Indians must stay and belong in that band, that we don't want no rebels from the Red Lake Reservation. If you go, whoever goes, I says, relinquishes their rights on Red Lake, because, I says, we're not going to war with the government."

Peter Graves was a powerful and controversial leader. Newspapers at the time of his death said some considered him one of the greatest Ojibwe leaders ever, while others considered him a dictator. In the 1950 interview, Graves talks about how he saw his role in the tribe.

"I grew up to civilize this band of Indians here," Graves said. "I was always on the side of the government, and there's a lot of them that doesn't like it, but they got to take it. When I say something, well, I mean it, and that is why I'm here today. Whatever I say, I mean. A lot of them threaten me. Well, I just tell them, 'you'd better be quick about it, or I'll get ahead of you.'"

Graves' grandson, Peter Strong, says his grandfather helped hold the Red Lake tribe together. Other Ojibwe bands in Minnesota at the time agreed to something called allotment. That meant tribal lands were split up and given to individual tribal members, who were free to sell their property to whoever they wanted. Graves and other leaders before him refused to accept that.

For Red Lake, that means all reservation lands are still owned jointly by every tribal member. Peter Strong says that saved the reservation from being snatched up by non-Indians.

"We wouldn't have any lakeshore land, that's for damn sure," said Strong, who figures the lake would have been invaded by cabins and resorts. "That's right, and we wouldn't own any of them. So it's been different for us and I think we're better off the way we are, you know?"

Strong left the Red Lake Reservation only briefly to find work. He worked in Minneapolis for a few years in the late 1950s. He spent a few years in the Army. But Strong says he just couldn't stay away.

"To me, I missed people talking Indian, even though I didn't understand it very well," said Strong. "Your family is here. And this is my land, this is my home, you know, the whole area. This is mine, this is mine."

Strong says that's the way it is for most Red Lake people. Even for the ones who build lives for themselves far away from the reservation, many choose to be buried at Red Lake when they die.