WWII Medal of Honor recipient laid to rest Saturday

Editor's Note: Funeral services are tomorrow in Duluth for the last living Medal of Honor recipient in Minnesota. Mike Colalillo earned the honor during World War II. The West Duluth resident died last week at the age of 86.

Nearly four years ago, Colalillo spoke with MPR's Mark Steil about his experiences during World War II. Steil's original report aired in January 2008.

---------

Duluth, Minn. -- Mike Colalillo was one of the few living Medal of Honor recipients from World War II. About 450 U.S. soldiers, sailors and pilots received the nation's highest combat award during the war. Only 32 are still alive. One of them is a former soldier from West Duluth, who earned the medal during the closing days of the war.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

The end of the European phase of World War II was in sight as 1945 began. In his first address to the nation of the new year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt went on radio to prepare the nation for heavy losses ahead.

But he said final victory was near because of what he called the "unforgettable gallantry" of the U.S. soldier.

"In all of the far-flung operations of our own armed forces, on land and sea and in the air; the final job, the toughest job, has been performed by the average, easygoing, hard-fighting young American who carries the weight of battle on his own shoulders," said Roosevelt.

One of those easygoing, hard-fighting young Americans was Mike Colalillo. Sitting in his apartment in West Duluth, Colalillo says he faced almost constant combat in early 1945.

With a fringe of silver hair circling his mostly bald head, Colalillo peers through wire-rim glasses into the past. He was 19 years old, part of a U.S. Army which was slowly pounding the Nazis towards a surrender that spring.

"We were greenhorns," says Colalillo. "The more you went into the combat, the more you knew then. A little bit more here and a little bit more there. Then you knew when to duck and when not to duck, and this and that. That's a long time ago."

The Americans soldiers pushing through western Europe faced a variety of battlefields. Street fights in cities and towns, following combat in the farm fields and woods which covered the land.

Colalillo quickly became a top-notch infantry soldier. In one fight, he and a buddy went out alone to destroy a couple of enemy machine gun positions. His feats were daring, but Colalillo says he was far from fearless.

"We were all scared anyway, and not only the other guy, but me too," says Colalillo. "When you're young like that, sometimes your adrenaline just comes to you and you're going, boy."

"I jumped on the tank and told them...'I'm going to use your machine gun.'"

On April 7, 1945, a month before the war in Europe ended, Colalillo's unit came under heavy fire in the open country near the German town of Untergriesheim.

"We were all pinned down, we couldn't move. If you get up we'd get shot at," says Colalillo. "We lost a lot of men there, oh God, we lost a lot of men in there."

Lying on the ground, bullets and shells flying everywhere, Colalillo decided something had to be done. Even though he was a private, not in command, Colalillo rose up and yelled to the other soldiers to follow him.

The soldiers fell in behind some tanks and moved forward, firing as they went. Shell fragments hit Colalillo's submachine gun, making the weapon useless, and leaving him even more vulnerable.

"I jumped on the tank, and just hollered in the tank and told them, 'I lost my gun and I'm going to use your machine gun on the top,'" Colalillo recalls. "And that's when I started shooting all these positions where the Germans were."

Out in the open on top of the tank, Colalillo rode into battle, firing the machine gun mounted on the turret. He destroyed two German positions, killing at least a dozen soldiers. When the machine gun jammed, he grabbed another weapon and moved forward on foot. Later, still under fire, he carried a wounded soldier to safety.

Another World War II veteran, Richard Spielman of Monroe, Wisconsin, remembers the day well. Spielman was in Colalillo's unit, though not in combat that day. He says news of Colalillo's exploits traveled quickly.

Spielman says one officer who was in the battle said Colalillo's tank ride was decisive.

"He said they were going to stand there and fire at us, and he said boy he took their pressure right off of that," says Spielman. "With Colalillo and his extravaganza there, the Germans pulled out pretty fast."

Spielman says the peril Colalillo faced in exposing himself to enemy fire became evident the next day. A detail of soldiers went back to the battlefield to retrieve the dead Americans. They saw just how brutal the combat was that Colalillo survived.

"They went up there and they found an arm here and a leg there and so on," says Spielman. "When these boys came back you didn't see any of them smiling. They just were pretty mum. They just didn't tell anybody anything. They just said, 'Well, we found some pretty bad casualties,' so that's the way it was left."

A week or so after the battle, the Minnesota soldier got a surprise. Army brass sent a jeep of military police officers to escort Colalillo to safety away from the front lines.

The tank commander had nominated him for the Medal of Honor. The military didn't want their newest hero killed in the last few days of a war where victory was certain.

On May 8, 1945, President Harry Truman announced the end of the war in Europe. Truman had become president a few weeks earlier, when Franklin Roosevelt died. A few months later, Mike Colalillo was on his way back to Minnesota.

"They asked us what we wanted to do, you want to go home or you want to stay in the service?" says Colalillo. "I said I'm going home."

He was discharged from the army at a base in Wisconsin. Colalillo took a train to Minneapolis. There, he and another soldier from West Duluth boarded a bus for home.

They celebrated on the final leg of their epic journey. It was a time of victory, a time to shed the shadow of death, a time to celebrate all the good things in life.

"Got a bottle, went on the bus, and we got drunk," says Colalillo.

A few months after that memorable bus ride, Colalillo was traveling again -- this time to Washington D.C. He and his family went to the White House to receive his Medal of Honor.

Although it's one of the nation's highest awards, it's something Colalillo rarely talks about. His friend and fellow World War II veteran, Tom Dougherty of Duluth, says Colalillo is a very humble man.

"The only thing that Mike ever said about it is, Harry Truman, as he was pinning the medal on, he said, 'I would have rather got this Medal of Honor than be the President of the United States,'" recalls Dougherty.

Dougherty says Colalillo may not talk about his Medal of Honor, but he says the public clearly is impressed.

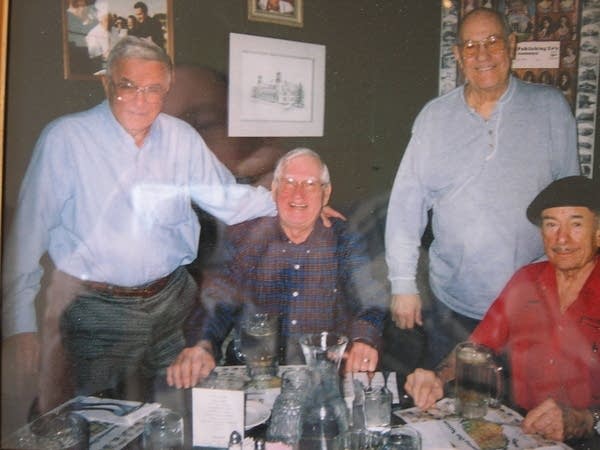

Dougherty remembers once when he, Colalillo and two other World War II veterans were having their regular lunch at a local restaurant. Dougherty says for fun, all four were decked out in matching green berets.

"This one fellow come down and he said, 'Just who the hell are you guys?'" says Dougherty. "I explained to him exactly what Bobby Wilson did in the service. And what Befera did in the service. I said, 'Oh, I almost forgot, Mike Colalillo here, he's a Medal of Honor winner.' And I thought this guy was going to collapse."

For Colalillo, the medal is something that's become more important to him as he gotten older. He's been widely recognized for the honor. There's a bust of him in the Duluth City Hall, a street's been named for him.

Still, he doesn't take his military honor too seriously. He says right from the beginning, his friends in West Duluth made sure that didn't happen.

"They said 'How could a little twerp like you get the Medal of Honor?'" says Colalillo.

The answer to that question emerges as Colalillo revisits the war. It's deceptively simple.

Pinned on the ground, he and his fellow soldiers were in a deathtrap. When Colalillo got up and marched forward into military history, he was just fighting to stay alive.