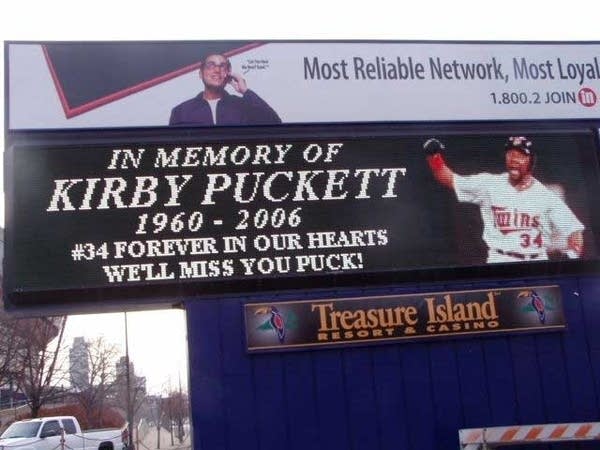

Kirby Puckett remembered

Kirby Puckett was one of the most popular athletes in Minnesota history. For a dozen years Puckett roamed the outfield for the Minnesota Twins -- leading the team to two World Series championships, and winning over teammates and fans around the country with his enthusiastic, fun-loving style of play.

For most of the 1980s and '90s, Minnesota Twins fans loved Kirby Puckett. But he seemed to have a special rapport with children.

"Probably because they're taller than I am," Puckett said with a laugh.

Puckett's ready laugh and hearty smile, the round build on his 5 ft. 8 in. frame, and the roll of his distinctive name, all contributed to a teddy bearish quality that made him irresistible to many of the youngest Twins fans.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Puckett spent his own childhood in the Robert Taylor Homes, a public housing project on Chicago's south side. When he was inducted into baseball's Hall of Fame five years ago, Puckett arranged for a team of youngsters from that same project to be on hand.

Their coach, Ziff Sistrunk, said at the time that Puckett's enshrinement had electrified the neighborhood.

"He's the example for all of Illinois, for all of Chicago to give inspiration. When you're talking about people getting shot and drugs around you every day," said Sistrunk at the time. "So, when you get an inspirational story like Kirby Puckett ... all over Robert Taylor Homes you're seeing people hanging No. 34 out. You're seeing people hanging banners out, the kids put together some paintings for him, schools put up marquees with 'Kirby Puckett.' It's tremendous. He's an inspiration."

[image]

The youngest of nine children in his family, Puckett remembered taking some lumps from his older siblings and from the bigger kids in the neighborhood.

His athletic career began with pickup games of stickball played on the concrete between the project's high-rise buildings. He played his first organized games in high school as an infielder, switched to the outfield while at Bradley University, and made his major league debut in 1984.

The Twins were on a road trip in Anaheim, California, when they called for him. Puckett was with his minor league team in Maine and spent the whole day travelling across the country to join them. Years later, he insisted that no thrill surpassed the excitement of his arrival in the big leagues.

"I walked up to the clubhouse and Randy Bush was the first guy I saw, and Kent Hrbek and Tim Laudner, and I called them all Mister, Mr. Viola," Puckett recalled. "I got there just in time to take a couple swings. And when I walked on that field in Anaheim I knew that I belonged, because I had worked so hard, and knew that ever since I was 5 years old that was my dream. And I got a chance to live my dream."

No matter where he was around a ballpark, there was life and there was energy. I can't think of one opposing player who didn't like Kirby Puckett.

There would be many more thrills over the next 12 years -- for Puckett and for the fans who flocked to the Metrodome to see him play.

Two years before Puckett's arrival, the Twins had suffered through the worst season in team history. Major League Baseball had recently endured the first labor dispute to force the cancellation of a big part of a season.

Some Minnesotans complained that the Twins' move to their new, indoor home was a part of the big business mentality that was taking the innocence -- and some of the fun -- out of baseball.

Two World Series titles later, those gripes were long forgotten, banished by a blizzard of Homer Hankies and replaced for Twins fans by sweeter memories, like WCCO radio's John Gordon calling Puckett's winning homer in the 11th inning of Game 6 of the 1991 World Series.

"Puckett swings and hits a blast, deep left center, way back, way back, it's gone! The Twins go to the seventh game! Touch 'em all, Kirby Puckett!" was the call.

In addition to the two world championships, there was a batting title, a Most Valuable Player award, 10 appearances in the All-Star game, and six Gold Glove awards for his fielding.

But it seems that what Minnesotans remember most fondly about Puckett are not his accomplishments as much as the kind of player he was -- starting with what he looked like.

Soon after word of Puckett's death, Vidal Allen of St. Paul was in a local watering hole, reminiscing about the fireplug of a body that wore No. 34.

"He wasn't a big, strong guy, because he had the big pot belly, y'know, a heavier guy. I remember I never really got into baseball until I saw Kirby Puckett," said Allen. "He was a little guy, but he could just knock the heck out of the ball. And I'm like 'Wow, look at this little guy swing!'"

A number of Minnesotans consider Kirby Puckett the most popular athlete the state has ever known. The Star Tribune newspaper named him Minnesota's athlete of the century. Greg Wong, a retired sportswriter who covered Puckett and the Twins for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, says various ingredients contributed to Puckett's appeal.

"He was a little guy, the little squat body. The smile. He always had that smile, just that infectious smile," said Wong. "And he always related to the little guy. He was a superstar player, but he didn't think he was a superstar off the field."

Puckett came to the ballpark early, stayed late, and seemed to enjoy every moment in between. Wong says the joy Puckett found in the game was obvious to fans, teammates, sportswriters, even his opponents.

"The clubhouse at the Metrodome would be kind of quiet and all of a sudden you knew when Puck was there. Things just livened up. No matter where he was around a ballpark, there was life and there was energy. I can't think of one opposing player who didn't like Kirby Puckett," Wong said.

Puckett's playing career ended suddenly. He woke up one morning shortly before the start of the 1996 baseball season, and found he could not see out of his right eye. Doctors eventually determined that he had glaucoma, and that the damage to his vision was irreversible. It was a somber day at the Metrodome when Puckett announced his retirement.

"Baseball's been a great part of my life, ever since I was 5 years old. I'm 35 years old sitting in front of you now, and I played baseball for 30 years. It's been a great part of my life. It really has," said Puckett at the time. "But now it's time for me to close the chapter on this book and baseball, and go on with part two of my life. It's going to be all right. Kirby Puckett's going to be all right. Don't worry about me."

Years later, Puckett reiterated that he felt no bitterness about the abrupt end of his career, only gratitude for the time that he did play.

"I never sat in the mirror and go, 'Why me?' I just thought that God or somebody wants me to have this disease to get the word out -- to spread the word to other people," said Puckett. "Because right now there's over three million Americans walking around with glaucoma right now."

Puckett's adjustment to life out of a baseball uniform seemed to go well for several years. He became a vice-president of the Twins and his popularity made him an ambassador of sorts, especially to children.

At a typical appearance in 2001, he told a group of summer campers in a university gymnasium that there was a "carpe diem" lesson in the premature end to his baseball career.

"The doctor told me, 'Mr. Puckett, I'm sorry you're not going to be able to play baseball anymore.' Everybody around me started to cry. But I didn't cry," said Puckett. "Because I just thanked God that I played those 12 years like I played those 12 years in the big leagues."

In his last years, though, Puckett's life was not as smooth. In 2002, Puckett was charged with false imprisonment and criminal sexual conduct, after a woman alleged he had pulled her into the men's room at an Eden Prairie restaurant and groped her before she was able to flee. Puckett was eventually acquitted of the charges, but his public reputation never fully recovered.

Puckett's appearances in court drew hordes of photographers and reporters.

Puckett's marriage soon ended in divorce. His front office job with the Twins was not renewed. He left the Twin Cities, relocating to Scottsdale, Arizona.

Some friends were reportedly concerned about his steady weight gain. Greg Wong suspects Puckett never really adjusted to life after baseball.

"He just loved the game. And I think the fact that he couldn't play anymore, and now he had all this time on his hands ... he wasn't around the guys ... I think that had some effect on the rest of his life, after that," said Wong.

In spite of his truncated career, Puckett was selected to be inducted in baseball's Hall of Fame as soon as he became eligible in 2001. His uniform number has been retired by the Twins.

Kirby Puckett leaves a son and daughter, who are 15 and 13. Kirby Puckett was 45.